|

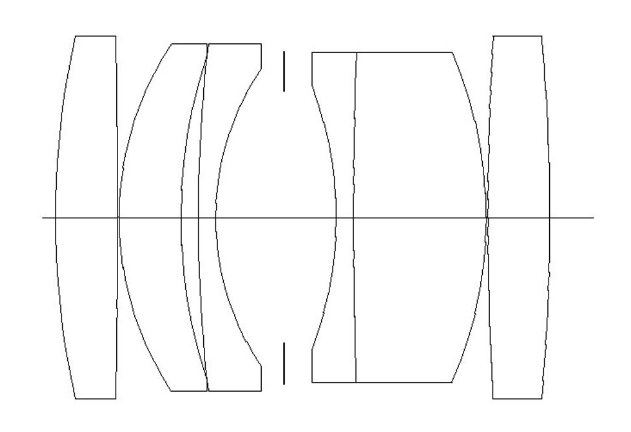

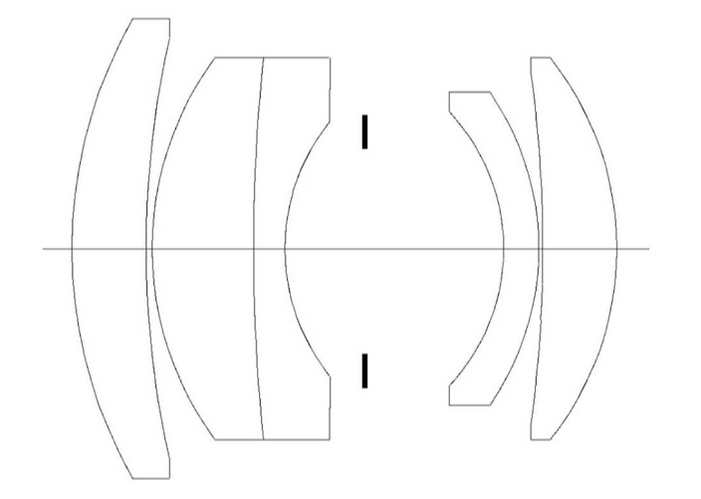

Updated Oct. 20, 2023 When it was released as the first of the AI-s Nikkors in February of 1980, the 55/2.8 Micro-Nikkor sported a 2/3-stop faster maximum aperture than its AI predecessor and, in a first for a Micro-Nikkor, Close Range Correction (CRC). CRC was Nikon's fancy acronym for a "floating" element focusing system. In contrast to a standard "fixed" focusing mechanism, where only one lens block or group moves to achieve focus, a floating system adds a mechanism to provide the capability to move another lens block or group in addition to the primary focusing unit. In virtually every category, the new lens offered improved optical performance to the older one. Yet, today, the popularity of the 55/2.8 is no greater than that of the 55/3.5, and dollar values are basically a wash despite the 2.8's greater complexity and performance potential. Weird. But how come? Let's dig in. Advantages of a Floating Element Optical Design Floating elements were patented at least as far back as 1958 (by Minolta), but the design concept was likely floating (pun intended :-)) around the minds of optical designers years earlier, but prior to the introduction of retrofocus wide-angle lenses during the 1950s, there hadn't been a pressing need to actually develop it into something tangible. The issue that these new-fangled wide-angles (try saying that five times, fast ;-)) presented was that they required relatively large, high-curvature lens elements which exacerbate optical aberrations, particularly at close focusing distances. This still wasn't a huge problem during the '50s, as close-up photography was not exactly mainstream and the new wide-angles were mostly being put to use in landscape and other scenarios where most focusing was done at the mid-to-infinity distances that almost all lenses were (and quite a few, even today) then designed to offer their greatest performance at. But the dawn of the SLR era would change all that. During the rangefinder era (mid-1920s to the end of the 1950s, roughly), close focusing was limited to about 0.7m (28") at best, due to the limitations of the rangefinder mechanism. This, combined with the restriction of being able to optimize a standard optical design (with its one moving lens block to achieve focus) for either near or far distances, but not both, precluded much in the way of development of a system that could allow for improved close-focus performance while retaining excellent capability at standard distances. The introduction of the first successful Japanese SLRs during the late-'50s, however, combined with the growing popularity of wide-angle 28mm lenses for the 35mm format, caused the manufacturers to take a closer look at alternatives to standard focusing mechanisms. SLRs had none of the rangefinder's limitations on close focus distance, and gave the added advantage of allowing the user to see the exact point of focus in real time. Being able to move a second lens group in concert with the primary focusing unit gave more flexibility in correcting the aberrations that were magnified by those high-curvature, wide-angle elements at close distances. In a standard early-'60s 24 - 28mm lens, close focusing was limited to 0.6m (24") at best, due to the dropoff in image quality caused by the magnification of those aberrations at close distances. And the wider you went in focal length, the worse it got. Almost ten years after Minolta patented their first floating element design, Nikon introduced the first production floating element lens and the CRC moniker along with it...the 24/2.8 Auto Nikkor-N of 1967. Close focus distance dropped to 0.3m (12"), a massive improvement. By the mid-'70s, almost all of the major Japanese manufacturers had adopted floating elements for their advanced wide-angles. But the optical engineers at Olympus had been thinking: if floating elements could improve close focus performance on a wide-angle that much, then what if we tried them in a dedicated 50mm close-up lens? Now that might at first seem superfluous...after-all wasn't that the whole point of close-up lenses, to be optimized for close distances?? Well...things were a bit more complicated than that. The reality was that almost all 50-60mm macro (or in Nikon's case "Micro") lenses were then optimized for a magnification ratio of 1:10 (or 1/10 of real life size). That added up to about 0.7m (28") or about the same as the absolute close focus for a 35mm rangefinder. So what gives? We now have to go back to the original purpose the 50 - 60mm macro/micro lens was designed for: photo duplication of documents. In fact, the original design brief for the initial Micro-Nikkor 50/3.5 (released in 1956) for the Nikon S-Series of 35mm rangefinders was to provide optical performance capable of resolving complex Japanese Kanji characters for reproduction on microfiche. Once they introduced the F-mount, Nikon added 5mm of focal length (accompanied by a corresponding amount of optical correction for this slight bump in focal length) to their existing Micro-Nikkor design to provide the necessary back focus required by the SLR. The original 55/3.5 Micro-Nikkor was thus born, and like its S-mount ancestor, it was optimized for distances much closer than 1:10 magnification and was/is capable of superb performance at those very close distances (it is also capable of 1:1 reproduction, without an extra extension tube, due to its double-length focusing helicoid). The price was that performance at further distances had to be sacrificed in exchange for that, along with automatic aperture operation. The problem that presented for Nikon (and everyone else) was that most users were not using their 50 - 60mm macro/micro lenses at those very close ranges. The average user wanted a bit more versatility, so in 1963, Nikon re-optimized the optics of the 55/3.5 for best performance at 1:10 reproduction instead, and thus sacrificed a bit of performance at super-close distances. In other words, a compromise (Nikon also dropped the double-length helicoid for a separate extension tube that allowed for 1:1 reproduction; without it the maximum magnification was 1:2. This also allowed them to incorporate their standard automatic aperture mechanism.). It was the best that could be done given the technical constraints of fixed-element lens designs at the time. Seeing as this new Micro-Nikkor was introduced before Nikon developed TTL (Through-The-Lens) metering, they also provided an automatic aperture compensating feature as the lens was focused at different distances to provide consistent exposures without having the user resorting to manual calculations to make such compensation. If you happen to prefer handheld non-TTL metering, this second-generation F-mount 55/3.5 Micro-Nikkor (1963-69) may be more appropriate for your use case than the follow-on third generation (1970-79) models that deleted this feature due to the near-universal adoption of TTL meters by that time. The optical formula remained unchanged across all generations of the 55/3.5, with changes in coatings (and other possible minor tweaks) being the only updating, proving the overall soundness of the original design. When Olympus released their OM Zuiko 50/3.5 Macro lens in late-1972, it was a revelation to the industry. Here was a 50mm macro that was the size and weight of the standard 50/2 Nikkor but that included the longer helicoid required for close-up work and the addition of a floating element that improved image quality at very close distances. A new standard had been set for 50mm macro versatility. So when Nikon was looking to replace the venerable 55/3.5 in the late-'70s there were two main briefs: 1) improve both the overall and very close focus optical performance, and 2) make the maximum aperture brighter. This begat the 55/2.8 Micro-Nikkor with CRC. And it fulfilled its objective (no pun intended ;-)). The 2.8 equalled or exceeded the 3.5 in almost every optical parameter. The new Gauss-type optical layout (6 elements in 5 groups) allowed for better close-up aberration correction and a wider maximum aperture than the Xenotar-based 3.5 (5 elements in 4 groups). Edge acuity, coma correction, and field flatness were all improved. But that came at a cost. To achieve those lofty goals, Nikon had to double the complexity of the focusing system (two separate helicoid systems: the outer primary and an inner one incorporating the CRC mechanism). Weight increased by just under 20% (not bad considering the addition of CRC and larger glass for the f/2.8 aperture, but still 45% more than the OM Zuiko 50/3.5). But that would prove inconsequential compared to two major problems that the 55/2.8 Micro-Nikkor would eventually suffer from. Compromise Comes to the 55/2.8 Whether it was due to trying to avoid violating the focus mechanism patent for the Olympus OM Zuiko 50/3.5 macro or simply a case of the NIH ("not-invented-here") syndrome that Nikon (and to be fair, other companies) occasionally suffers from, the resulting CRC helicoid design led to two major long-term problems for the 55/2.8. The first is that with two focus helicoids that each have three mating surfaces, there is roughly double the amount of friction to overcome when it comes to focusing. You can easily feel the difference in the torque required to start turning the focus rings on the 2.8 and 3.5, with the 3.5, logically, taking about half the effort to turn. This is with both lenses having been freshly re-greased with #10 grade helicoid lubricant. But it is when the grease begins to break down that you really start to have problems with the 2.8. First, focusing gets progressively stiffer and if the lens happens to sit for a long period of time, as many manual focus lenses have had to endure over the past 30+ years, it will simply seize. It took me a good thirty to forty seconds to turn one 55/2.8 from full extension (which is how it arrived) back to infinity with a very firm two-handed grip and constant torque applied. On the other hand, while my personal 55/3.5 arrived with the dry, gritty feel common to 40+ year old Nikkors, there was no problem in turning the focus ring (and after servicing it is pure buttah ;-)). The 55/2.8 simply cannot compete on focus feel with the 3.5, and requires more frequent servicing to remain usable. When freshly greased and used regularly it works just fine, and if you prefer a bit stiffer focus feel for close-up work, you may even find it advantageous. The second issue is a clear-cut deficiency in design, however. And it is directly related to having the CRC helicoid unit directly above and with unfettered access to the aperture assembly. When (not if) the helicoid grease degrades, particularly from disuse, the base oil separates from the soap. The abandoned soap is what stiffens/seizes the helicoids, while the oil goes where gravity and capillary action take it, which almost invariably happens to be the aperture assembly that sits right at the base of the CRC unit when the lens is stored in the position that 99% of us store all of our lenses: sitting upright on the rear cap. Oily aperture blades are an all-too-common result, with a worst-case scenario of a completely stuck aperture. Rumors persist that Nikon did some later internal redesign or changed the grease (the more likely of the two) to mitigate this problem, but I have been unable to find authoritative corroboration for this, as of yet. I can state with confidence that stiff/seized focus rings and oily/seized apertures can be found up to serial numbers beginning with 596xxx at least, which is over 417,000 units into production. Stated another way: at least 85% of all 55/2.8 AI-s lenses produced are susceptible to these two issues. And that is why you can always find a 55/2.8 with either or both problems for less than a 3.5 Micro-Nikkor in otherwise-comparable optical and cosmetic condition. That is not to say that you cannot find a 2.8 that has never experienced either of these ailments, but you definitely need to be on the lookout for them when considering one for purchase. Sitting unused for a long time in a hot environment is probably the worst combination of circumstances for a 55/2.8 Micro-Nikkor to find itself in. If the aperture is dry and the focus OK, a 55/2.8 will rightly be priced higher than a 3.5, but you have to usually travel quite a bit higher up the price chart and be very thorough in checking it over before making that purchase with confidence. Or, alternatively, budget in the cost of a proper CLA (Clean, Lube, Adjust) to get a low-priced-but-needing-service copy into game shape. Which to Choose? The big question to answer when choosing between these two lenses (to be clear: we are talking about the non-compensating f/3.5 built in Micro Nikkor-P, Micro Nikkor-P-C, K, and AI versions offered from 1970-79 and the AI-s f/2.8 from 1980-2020) is: What does your usage case consist of?

Wrap-Up Each of these lenses remains very versatile and they are both available for less than a 50/1.4 any day of the week. They can do a very credible job wide-open for portraits on an APS-C sensor digital body, and are great for stationary objects that you want to get closer to. No 50 - 60mm macro/micro lens is suitable for insects or other small creatures as the working distances are just too small. If you find either one for cheap with the optics in good shape, don't hesitate to grab it, even if a CLA will be needed to set it to rights. As far as image quality for the dollar, you would be hard pressed to find a better lens (and that goes in general for almost all 50 - 60mm macro/micro lenses). They make great walkaround lenses too, with that ability to get closer than a standard 50 when you want to go for those smaller details. At normal distances they focus just as quickly as your regular 50s, with roughly half of their focus rotation coming below 0.4m (16"). With their 300-degree, long-throw helicoids, precise focusing is a breeze and infinity is spot on with these lenses. The 55/2.8 gives you a bit more flexibility if you are a Program or Shutter-Priority user with its AI-s compatibility, but most of the time you use such lenses, control of depth-of-field (DOF) is more important, making that a moot point. In terms of rendering at distance, the 55/3.5 is reflective of its design roots in the 1950s & '60s (more "vintagey" ;-)), with the 55/2.8 being more modern as befits the late-'70s when lens design in general became less artistic and more scientific. If you do end up with a 55/2.8, be sure to store it with the rear of the lens facing up. That will make it more difficult for any loose oil to migrate to the aperture blades. Other than that, pick the one that best captures the look you like. Or you can always get both. Decisions, decisions... :-) References: Nikkor - The Thousand and One Nights No. 25 (Part I) @https://imaging.nikon.com Nikkor - The Thousand and One Nights No. 26 (Part II) @https://imaging.nikon.com Nikkor - The Thousand and One Nights No. 85 @ https://imaging.nikon.com Olympus OM-1 Sales Brochure (1973) @ https://www.pacificrimcamera.com Micro-Nikkor 55mm f/2.8 Instruction Manual Micro-Nikkor 55mm f/3.5 Instruction Manual Roland's Nikon Pages @ http://www.photosynthesis.co.nz/nikon/lenses.html

6 Comments

Melvin Bramley

3/21/2023 09:30:58 pm

I have too many cameras and lenses.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

3/21/2023 09:46:03 pm

Can't go wrong with that combo, Melvin. And I agree, you can't lose either way :-).

Reply

4/4/2023 12:23:44 am

I like both of the 55s. I had a 3.5 that was perfect, but I found myself using the 2.8 more often and sold the 3.5.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

4/4/2023 10:35:21 pm

Nice to hear from you, Gil. It sounds like you are well-stocked in 2.8s :-). Your two working copies give you the luxury of time when it comes to fixing the others. Definitely worth hanging onto when a CLA is all it will take to resurrect them, should the need arise. I have had my 3.5 for longer, but I can definitely forsee the newcomer 2.8 grabbing a bit more of the action over time. They both have their strong points but they give a very similar overall look when it comes to color, etc. Just great bang for the buck, either way. Take care.

Reply

Andy Carlson

8/21/2023 12:25:28 pm

Enjoyed this post. I have both of these lenses and I like both. The 3.5 came with my Nikkormat FTN for the grand sum of 37 of our English pounds. Both camera and lens needed and have had a DIY overhaul and are now doing good service. The 2.8 cost me a good deal more and didn't need any work... not sure I am brave enough to go in there TBH. I have at least flipped the 3.5 so that it is the other way up on the shelf now :) The 2.8 came in one of those plastic dome things... which rather compels the aperture downwards orientation on the shelf. It's living on the camera at the mo.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

8/21/2023 12:56:25 pm

Nice to hear you enjoyed it, Andy. I haven't noticed much of an issue with oily blades on the 3.5s, so you should be alright with either orientation for storage. As for the 2.8, I would do just as you have...just leave it on the camera, or use the standard front and rear caps for storage and use the bubble for another lens. Whatever works best for you. Enjoy both. Best regards.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed