|

Updated May 29, 2024 When Canon management decided on March 31, 1985 to embark on a two-year program to develop a completely clean-sheet auto focus (AF) 35mm SLR system, they were granting Minolta a two-year head-start in that burgeoning market. This was a result of the instantaneous success of the Minolta 7000, introduced almost two months before. Canon realized that their first FD-mount AF SLR, the T80, due to be introduced in April of that year, was completely outclassed by the 7000 and bold measures were thus imperative. Consequently, Minolta had the 35mm AF SLR market to itself for 14 months, until Nikon introduced their F-501 (N2020 in USA) in April 1986. Right on schedule, in time for their 50th anniversary as a camera manufacturer, Canon brought out the EOS 650 on March 1, 1987. Within two months, it became the top-selling AF SLR in Japan and Europe and was a match and more for the 7000 and F-501. But Minolta had not been sitting idly by. The summer of 1988 brought their second-generation enthusiast AF SLR, the Minolta 7000i, which was a huge jump forward from its not-exactly-ancient ancestor, as is usually the case in the early stages of the growth cycle of any technology. Canon had caught up to (and surpassed in a few areas) Minolta's and Nikon's first-gen AF SLRs, but how would the second generation of EOS fare against a much more sophisticated competitor?

0 Comments

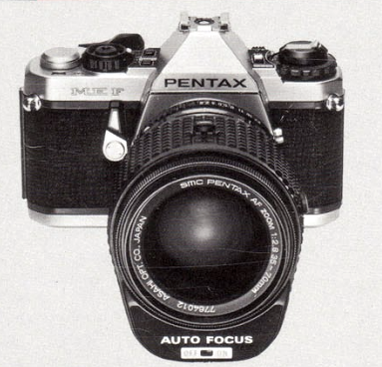

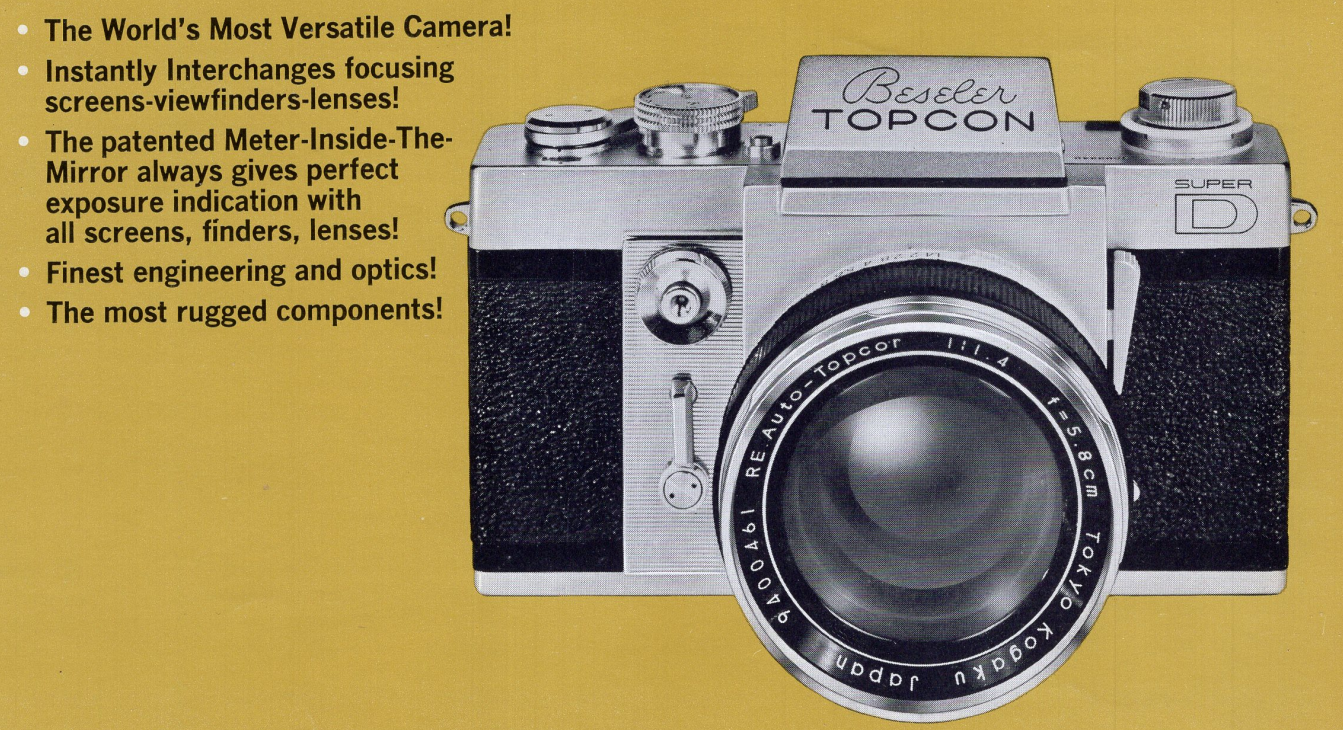

Regular visitors to this site may have noticed a bit of a trend: As much as we love the classics, we also have a thing for "sleepers", those anti-Instygrammy, tacky Tik-Tok-immune cameras that do one thing: take great pictures ;-). And if you are looking to dabble in a bit of film, but don't feel like auctioning off a body part or two to look all the business, here is yet another option to consider... Although they came late to the 35mm Auto Focus (AF) SLR party in 1987 (trailing Minolta by just over two years, and Nikon by 11 months), when Canon debuted their EOS 650 (March 1987) and EOS 620 (May 1987) models, they rapidly closed the gap to their two main competitors. Within two months of its introduction, the EOS 650 became the best-selling 35mm SLR in Japan and Europe. The 650 was easily a match, technologically, for its main competitors: the Minolta 7000 and Nikon N2020 (F-501 outside North America). When combined with Canon's decade-long lead in marketing prowess, it was a recipe for success. However, Canon's initial delay in the AF market meant that they would not have their second-generation EOS models ready until 1990, while both Minolta and Nikon would both introduce theirs in 1988. As with any new technology, the improvements in early generations are markedly larger than in later ones. And so it was with AF SLRs. The Minolta 7000i and Nikon N8008 (F-801 outside North America) were massive leaps from their forebears and vaulted both back ahead of Canon in the AF techno-battle. How would Canon respond? Well...it's happened. A Mamiya 35mm SLR has finally found its way into my grubby little paws. Sitting forlornly in a local thrift store, encased in a period vinyl case upholstered in the finest of green corduroy, with the assorted detritus of Kodak lens tissues, a bag of eyecups (none of which fit the eyepiece, of course ;-)), and a fourth-party flash and bracket, it soon came home with my friend after a quick exchange of text messages. Three hours later, I opened the case to that particular aroma only decades of storage can provide. Not unpleasant at all; in fact, distinctively delightful to a vintage camera nerd ;-). The original (n)ever-ready mamiya/sekor case was doing the typical crack & crumble as is the wont of such; nevertheless, it had done its job of protecting the important bits inside: a 1000 DTL and its accompanying AUTO mamiya/sekor 55/1.8 lens. A quick visual perusal showed nary a ding or dent, just an accumulation of dirt and light surface wear on the prism housing. The lens looked clear...the viewfinder pretty dusty...and then came the letdown... Konica (Konishiroku)...the original Japanese photographic company, and the first of only two full-line manufacturers (meaning both equipment and consumables such as film, paper, and chemicals), with Fujifilm being the second. Often overlooked among the Japanese 35mm SLR manufacturers due to its small slice of market share, and running a distant third to Kodak and Fujifilm when it came to consumables sales during the last four decades of the film era, Konica nevertheless was very influential in both sectors well into the 1980s. They also played a large role in the enforcement of the JCII standards for all Japanese optical equipment sold for export from the mid-1950s - '90s, supplying the optical testing lenses used in the assessment process for all of the other manufacturers (many of which, ironically, went on to have more notoriety in the photographic community than Konica's own underrated Auto Reflex or AR Hexanon lens lineup). Konica had a reputation for innovation: they were part of the Japanese consortiums that developed the first metal-blade, vertical-travel focal plane shutters and improved rare-earth optical glasses in the early-'60s; then they introduced the first Japanese autoexposure SLR (the shutter-priority Auto-Reflex) in 1965, and subsequently added through-the-lens (TTL) metering to that in 1968 (the Autoreflex T). Fast forward to 1979, and the FS-1 would prove to be the progenitor of the final generation of Konica's AR-mount 35mm SLRs, while introducing more industry-firsts. But the seeds of Konica's SLR demise would unwittingly be sown simultaneously...  1981 saw some major technological milestones: the first manned orbital mission of the Space Shuttle...the debut of IBM's Personal Computer (aka the PC)...the first flight of Boeing's second-gen wide-body, the 767...and the first Delorean DMC-12s began to roll off the line in Ireland. In step with such advancements, Pentax sought to push the technological boundaries of the 35mm SLR, much as they had a decade earlier with their Electro Spotmatic (ES) aperture priority autoexposure model. Only this time it was focus rather than exposure that they were seeking to automate. In late-'81, the ME F would become the first production 35mm auto focus (AF) SLR (with a caveat ;-)) to hit the scene. Updated June 21, 2022 Canon's A-Series of 1976-85 was, unquestionably, the most commercially successful lineup in SLR history. In excess of 14 million bodies (divided among six models) were produced. The A-Series came...they saw...they conquered...and then they did what all empires eventually do...slid into oblivion. The AL-1 QF was the final desperate gasp for the chassis, as Canon sought to milk the last drop from its traditionally-styled SLRs, with the oh-so-'80s T-Series waiting in the wings. Along the way, it upheld the lofty A-Series' ideals of bargain-basement battery door latches, consumer-conscious construction, and Canon's time-honored tradition of over-promised performance resulting in mass consignments to drawers, closets, and attics ;-). What's that, your eyes are glazing over already?? Fear not, dear reader...you may well end up having a refreshing power nap before this is all over ;-). Updated Jan. 10, 2023 Although Canon was not the first to the 35mm lens-shutter AF (auto focus) party with their Sure Shot (aka AF35M in Europe, aka Autoboy in Japan) model, with it they did introduce the auto focus technology that would come to dominate that burgeoning market until digital came on the scene. Not to mention, the Sure Shot was the first compact 35mm to combine AF with automated film winding and rewinding at the push of a button, i.e. the first proper Point & Shoot. The Sure Shots would go on to be the most commercially successful P&S lineup for the next 25 years. Updated Mar. 8, 2024 As the purveyor of choice for professional SLRs for over three decades, it shouldn't come as a surprise that Nikon was among the more conservative of manufacturers. After all, most professionals in any field are inclined to stick with the tried-and-true over any newfangled gee-whizzery that comes along. Case in point: the original F lasted in production for 14 years, the whippersnapper F2 for 9, and the last bastion of manual focus pro Nikons, the F3, stuck around for 21 years. Likewise, the enthusiast-targeted FM/FE/FA platform barely changed in layout (a couple of minor control changes from the original FM to FE in 1978, and in the final FM3A model of 2001 being the biggest modifications) in nearly a quarter-century of production. So when Nikon did make major design changes, even in their non-professional models, it was a...big...deal. The summer of 1988 brought such a change, the DNA of which has managed to leapfrog from the venerable F-mount (in both film and digital forms) to the latest Z-mount mirrorless models. Worst of all for Nikonistas, it originally came from C...C...C...Canon (aaauuuggghhh!!!). Updated May 10, 2024 Ka-Chang! Ka-Chang! Ka-Chang! The 1980s were anything but unobtrusive, so it should come as no surprise that the N2000 (F-301 outside of the US & Canada), Nikon's first SLR with internal, automatic film winding, was not bashful in its efforts to advance 35mm film to the next frame. This by no means distinguished it from its peers as there were no truly quiet motorized film advances until the '90s came along. Long spurned by Nikonistas due to its cardinal sins of: 1) Complete battery reliance, 2) Hybrid construction (READ: it's not all-metal...gasp!), and 3) Automation for everything but film rewind and auto focus, the N2000 is an all-time sleeper among Nikon SLRs (although the ruckus it makes when you squeeze the shutter release would serve as an effective alarm tone on your smartphone ;-)). It was Nikon's last proper, in-house, clean-sheet, manual focus SLR design (don't get me started on the FM-10/FE-10 imposters or the oddball N6000/F-601M that supposedly replaced the N2000, but was just a de-contented MF version of the AF N6006/F-601). But there was more to this under-the-radar SLR than just a fancy film advance system. Updated Feb. 17, 2022 Maybe tomorrow, I'll find what I call home, Until tomorrow, you know I'm free to roam. So if you want to join me for a while, Just grab your hat, come travel light, that's hobo style. -- excerpt from "Maybe Tomorrow", theme song from "The Littlest Hobo" -- The revival of The Littlest Hobo aired on Canadian television from 1979 to 1985 and continued in syndication throughout the rest of (and beyond) my childhood. I didn't like dogs much at the time so I thought that the show was by turns hokey, cheesy, lame...you name it (Macgyver was far more suited to my rarefied juvenile tastes and definitely not cheesy or hokey at all ;-)). Little did I realize that a similar situation was occurring simultaneously in the world of Nikon SLRs. Please allow me to introduce the hobo family of Nikon SLRs that was introduced in 1979 and discontinued in 1985 (coincidence or convergence? You be the judge ;-)). Updated May 21, 2021 Game Changer. An overused phrase nowadays to be sure, but when applied appropriately it conveys an unmistakable break with the past and an opening up of previously unthought-of possibilities. So it was with the Bobby Orr of SLRs - what came to be called the Olympus OM-1. Bobby Orr??? It's like this, eh. Like Bobby Orr totally changed hockey forever, eh. Like, before Bobby Orr, defensemen didn't lead the rush, eh, or score more than 21 goals a season, eh (he did so for 7 consecutive years, topping out at 46 in 1975), or like score more than 60 points in a season, eh (he scored over 100 for 6 straight years, winning two scoring titles along the way, something no defenseman has done before or since). Or win MVP, eh (three years consecutively, only one other defenseman has won MVP once in the last 50 years). Or win Best Defenseman in the league like eight times in row, eh. And he did all that on like, one knee, eh (his left knee was first seriously injured in his second year in the NHL and he would have 13 or 14 surgeries on it over the course of his career). But his effect on the game was far more pronounced than just the record books. Offensively-minded defensemen (paradox, anyone? ;-)) became indispensable in hockey. Arena construction went nuts in New England as thousands of kids were turned on to hockey by "numbah foah, Bawbee Oah". He turned casual or non-fans into hockey lifers. GAME. CHANGER. In the same era, the Olympus OM-1 did likewise for 35mm SLRs. In this article we will concentrate mostly on the features, operation, and handling of the OM-1 and how it changed the SLR landscape and 35mm photography forever. Updated Nov. 10, 2022 Canon. The bane of the 35mm purist's existence. Has any other manufacturer done more to suck the soul out of these beautiful machines with microprocessors, green rectangles for grubby-fingered greenhorns, and punished us with a plethora of polycarbonate, penta-mirrored, pale imitations of a proper SLR? And worst of all, to dominate the market for the past four-plus decades while doing so?! Ugh, there will be copious amounts of antacids and Gravol needed to make it through this one ;-). But if Big C had been such a force since the mid-1970s, why would they need to "catch up"? Read on...if you dare...bwahahahahaha... Updated Mar. 16, 2021 The Pentax K1000. The Minolta X-700. The Nikon F3. When it comes to naming the Japanese 35mm SLRs that remained in production the longest, those three models are at the top of most lists with both the Pentax and Nikon breaking the two-decade barrier (21 years for the Pentax and over 20 years for the Nikon to be more exact), and the Minolta clocking out after 19 years. Unsurprisingly, all three of these models are very popular with film enthusiasts today, with the Pentax and Minolta routinely being recommended as "Best Beginner Film SLR" and the Nikon being lauded as an all-time classic and sometimes espoused as the "Best 35mm SLR of All Time". The objective of this article is not to wade into any fray over "the Best..." (seeing as what's best for me or you will not necessarily be the same in any case), but rather, to introduce you to another entrant in the longest-produced sweepstakes; one that receives far less notoriety, yet can prove to be an excellent choice as an introduction to film photography. Updated Jan. 20, 2023 1957. A year of events that would reverberate for years to come. Sputnik. The debut of cable TV in the USA. "I Love Lucy" ended production. The Cat in the Hat was published. And a musical duo that would be as influential as anyone on the next two decades' of popular music (the Beach Boys, Beatles, and Bee Gees were only a few among the many that would cite themselves as being significantly impacted by them) had their first #1 hit: 1957 would also see the introduction of the first 35mm SLR from a relatively small Japanese manufacturer that was to have an outsized influence on the industry that would continue for over thirty years. In that year, TOPCON (Tokyo Kogaku) would find themselves at the leading edge of 35mm SLR technology and they would remain there for the next decade. The 1960s would see them emerge as Nikon's (Nippon Kogaku) most serious competitor in the professional 35mm SLR market. By 1977, however, Topcon's photography division would be a shell of its former self, outsourcing its remaining SLR production and diving right to the bottom of the market. By 1981 (with Nikon owning over 75% of the pro market), Topcon was out of the 35mm business completely, even though they live on to this day in the industrial and medical optics arenas. So, what happened? How did Topcon go from industry leader to also-ran in the space of a generation? Updated July 23, 2020 PROGRAM...the buzzword for SLRs in the early 1980's. Only with this technological breakthrough could photographers now surmount the barrier of having to think about camera settings and composition at the same time! Freedom from Aperture- or Shutter-priority or (heaven forbid you were still using) m...mm...mmm...Manual exposure beckoned. At last, focus (no pun intended) only on composition...unencumbered by such banalities...and our wunderkamera will do it all better than you ever could, anyways...(Okay, okay, that's enough...1980's marketing-speak now set to OFF). Riiight. Anyhoo, Program was going to be the next big thing to save the Japanese manufacturers from the the slippery slope of the latest SLR sales slide (Aside: it didn't ;-)). From the introduction of the Canon A-1 (1978), the first proper Program mode SLR (along with the three more familiar exposure modes mentioned above), to the 1985 introduction of the real "next big thing" (Auto Focus), the profligate proliferation of Program SLRs only accelerated. Followers included: Fujica's AX-5 (1979), Canon's AE-1 Program (1981) & T50 & T70 (1983 & '84), Minolta's X-700 (1981), Nikon's FG & FA (1982 & '83), Olympus' OM-2S & OM-PC/OM-40 (1984 & '85) , Ricoh's XR-P (1983), Yashica's FX-103 Program & the Contax 159MM (1985), and the two subjects of this article: the Pentax Super Program (1983) and Program Plus (1984). That's 16 models within seven years. So what set the Pentaxes apart from the rest of their competitors? Read on at your leisure ;-). Today, weathersealing is taken for granted as a common, although not ubiquitous, feature in cameras. Over 30 years ago, however, it was rare in professional SLRs (the Pentax LX being the only model with what would now be considered to be even a modicum of such protection) and non-existent as far as any enthusiast or consumer-level 35mm model went. A plastic bag and some elastics were the standard means of improving the survivability of your rig in the rain or at the beach, with all of the compromises that implies. The time was ripe for innovation. And who better than Olympus to shake things up? Updated Sept. 13, 2021 Canon the innovator...Canon the boundary pusher...Canon the...wait just a minute! Are we talking about the same Canon that moves today at what appears to be a less-than-glacial pace? Nope, we are talking about the Canon of over three decades ago...the vintage Canon ;-). A Canon that, while still the market leader, was determined to meet a declining SLR market with more than retrenchment. From an all-time peak of nearly 7.7 million SLRs sold in 1981, by 1983 sales for all brands of SLRs had fallen by over 30%. Sound familiar DSLR users? Canon had wrung the last drops from their A-series of SLRs (1976-84), the most successful line of manual focus SLRs ever, and the catalyst to the SLR boom of 1976-81. The question now facing Canon (along with very other SLR maker) was: Where to go from here? Their first response would be the T-series of SLRs (1983-1990). So how did that work out for them? From a sales perspective, the T-series failed to accomplish Canon's goal of revitalizing the SLR market. Each model seemed bedeviled by at least one Achilles' heel. But one thing was for certain, the problems came down to execution and timing, not a lackadaisical attitude on Canon's part. And ironically, out of the (relative) failures of the T-series would come Canon's greatest period of success, the seeds of which were sown by the most tragic of the Ts...the T90. Updated Oct. 19, 2021 The mid-1960s were heady days in SLRland. From 1964-66 all of the Big 4 Japanese manufacturers brought out new top-of-the-line enthusiast models: the Pentax Spotmatic (1964); the Nikkormat FT (1965); Canon's Pellix (1965) and FTQL (1966); and the object of our attention in this article...Minolta's SRT (1966). The feature all of these cameras had in common was: built-in through-the-lens (TTL) metering. We take it for granted now, but five decades ago this was revolutionary. Of the five models, the Pentax and Canons used stop-down metering (meaning that the photographer had to manually close (stop-down) the aperture on the lens to get an accurate reading and then focus at maximum aperture). The Nikkormat offered full-aperture metering (the lens remained at maximum aperture for the brightest view and ease of focusing while the meter reading was taken), but required the user to manually index the aperture ring every time that they changed lenses. Then came the SRT-101. Full-aperture metering and the aperture automatically indexed whenever you mounted a lens. No muss, no fuss. And all it took was: Updated Oct. 19, 2022 At first glance, the FE (along with its slightly-older sister the FM) is as nondescript a Nikon as there ever was. Its specifications are nothing out of the ordinary for a late-'70s enthusiast SLR: 1/1000 sec. fastest shutter speed, Nikon's venerable 60/40 centerweighted metering, sub-600 gram weight, and a seeming dearth of innovation. Looks? Nothing to see here people...move along...move along. Flanking the classic Nikon logo on the pentaprism housing are two virgin swathes of metal betraying no clue as to the identity of this wallflower. Only once you go to bring the camera to your eye is there the possibility of positive identification, that is, if your right thumb isn't already covering the tiny "FE" that precedes the serial number on the rear of the top plate. But don't sleep on the FE, there is more here than meets the eye ;-). Canon got off to the slowest start of the original Big 4 Japanese camera makers (Minolta, Nikon, & Asahi Pentax were the others) when it came to SLR development and sales . This was partially due to their commitment to interchangeable lens rangefinders for longer than their competitors. By the mid-1960s, however, they had embarked on a slow but steady climb that would lead them to market dominance by the late-1970s. Their first truly competitive SLR was the FT of 1966, and it would spawn one of the finest series of mechanical-shuttered enthusiast SLRs of the age and Canon's most successful non-A-series manual focus model. The second- and third-iteration FTb & FTb-N would prove to be the backbone of Canon's amateur lineup in the first half of the '70s and sold extremely well while both Pentax and Minolta were facing declining sales of their excellent Spotmatic & SRT mechanical SLRs at that time. That alone makes it a pivotal model in Canon's history. But it is much more than a sales footnote, it was one of the best enthusiast-level SLRs of its day, and that makes it a great choice today for the film-SLR aficionado. You could call the FT the analog 5D of its era :-). Updated Aug. 11, 2023 1975 saw the introduction of the CONTAX RTS, the first camera since 1961 (when the Contax IIa/IIIa rangefinders were discontinued) to bear that moniker and which was the firstfruits of the technological alliance between Zeiss (owners of the Contax name) and Yashica, the Japanese camera maker (who did the actual manufacturing). The RTS (which stood for Real Time System, to emphasize the supposedly superior responsiveness of the body) was aimed at professionals and serious enthusiasts with pocketbooks sufficiently large to take on the task of mounting pricey Carl Zeiss glass in front of it. The RTS was a success, but as Nikon had found out two decades earlier with the F, having a single model camera lineup that aimed towards the high-end of the SLR market tended to limit opportunities for sales (less cameras sold = less lenses & accessories sold ;-)). So, four years later, in a move that mirrored Nikon's introduction of the enthusiast-oriented Nikkorex F in 1962 (followed by the more-successful Nikkormat of 1965), CONTAX/Yashica introduced their CONTAX-badged contender in the very-competitive amateur market. But what does this have to do with the Yashica FX-D? Let's find out :-). Updated Mar. 8, 2024 Maybe it has something to do with the application of the term "vintage" to items over 30 years old, but there is a dead space for most cameras (and many other manufactured goods) that are in the 15 - 25 year old range. Not elderly enough to evoke nostalgia, and far from the cutting edge of current technology, they languish in a veritable no-man's-land. The subject of this article, the F90(X), is in such a place today. If you are a 35mm bargain hunter, and are willing to look past its plebeian polycarbonate pelt...your ship may just have come in :-). Updated Mar. 8, 2024 Coming-of-age. If any term could be applied to Nikon's auto focus SLRs from 1986 to 1991, that one has to be at the top of the list. The transition to AF maturity coincided with Nikon's rise to second place in the overall SLR market to essentially form a duopoly with Canon as the other members of the then-Big 5 (Minolta, Olympus, and Pentax) slid further and further behind, and in Olympus' case, dropped AF SLRs completely. The irony in all of this was that Minolta had gotten the drop on everyone and dominated the first few years in AF SLR sales with their groundbreaking 7000 model. Canon brought out their T80 FD-mount SLR a couple of months after the 7000, and it wasn't even close to the Minolta. So much so, that Canon abandoned further FD-mount AF development and began a crash program to come up with a completely new mount and SLR system. It would be two years before they brought out the EOS 650. For Canon, that would turn out to be time well spent, as the EOS cameras rocketed them to AF SLR sales leadership in rather short order. Nikon got on the board in April of 1986 (over a year after the 7000 made its not-so-subtle entrance). While the F-501 did not surpass the 7000, it was the first true competitor to the Minolta and gave Nikon a toehold (and critically, a one-year head-start over Canon to get established in the market) until they could bring out their second generation enthusiast AF SLR in 1988. By the mid-'90s Nikon had clawed their way past Minolta and tried to maintain pace with Canon in market share (which didn't happen, but they did comfortably establish themselves in second place :-)). Let the retrospecting begin... With a major SLR slump under way, the early-to-mid-1980s were the golden age of the compact AF (auto focus) 35mm camera. Many snapshooting consumers, who had been sucked in by the snake-oil promise of SLRs that did everything for you, now turned to what they had really needed all along: relatively affordable compact AF models. Innovations were coming fast and furious, and widespread cost-cutting had yet to enter the picture. All of the major (and most of the smaller) manufacturers had at least one high-quality entrant in the hotly-contested 35mm f/2.8 category. By the late '80s, however, the bean-counters and the public's clamor for zoom lenses ensured the demise of the capable, yet economical, AF compact. But let's go back to the boom days of... 1966 brought twin model introductions from Minolta that would lay the foundation for their next decade of rangefinder cameras. The nearly identical Hi-Matic 7s and 9 both featured Minolta's new CLC (Contrast Light Compensator) metering, which would serve as the top-of-the-line exposure measurement system for Minolta SLR and rangefinder cameras until the introduction of the AE-S Finder (1976) for the professional XK/XM SLR followed by the introduction of the enthusiast-oriented XD in 1977. Let's take a closer look at the Hi-Matics and the 7s in particular... |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed