|

Updated May 21, 2021 Game Changer. An overused phrase nowadays to be sure, but when applied appropriately it conveys an unmistakable break with the past and an opening up of previously unthought-of possibilities. So it was with the Bobby Orr of SLRs - what came to be called the Olympus OM-1. Bobby Orr??? It's like this, eh. Like Bobby Orr totally changed hockey forever, eh. Like, before Bobby Orr, defensemen didn't lead the rush, eh, or score more than 21 goals a season, eh (he did so for 7 consecutive years, topping out at 46 in 1975), or like score more than 60 points in a season, eh (he scored over 100 for 6 straight years, winning two scoring titles along the way, something no defenseman has done before or since). Or win MVP, eh (three years consecutively, only one other defenseman has won MVP once in the last 50 years). Or win Best Defenseman in the league like eight times in row, eh. And he did all that on like, one knee, eh (his left knee was first seriously injured in his second year in the NHL and he would have 13 or 14 surgeries on it over the course of his career). But his effect on the game was far more pronounced than just the record books. Offensively-minded defensemen (paradox, anyone? ;-)) became indispensable in hockey. Arena construction went nuts in New England as thousands of kids were turned on to hockey by "numbah foah, Bawbee Oah". He turned casual or non-fans into hockey lifers. GAME. CHANGER. In the same era, the Olympus OM-1 did likewise for 35mm SLRs. In this article we will concentrate mostly on the features, operation, and handling of the OM-1 and how it changed the SLR landscape and 35mm photography forever. An Auspicious Debut At its unveiling in July 1972 (after five years in development), Olympus designated the camera M-1, after its chief designer, Yoshihisa Maitani. And the entire system to be built around it was to be the M-System. That was all hunky dory until Leitz saw it at Photokina in September of that year, threw a hissy fit, and protested that only they had the right to use the "M" designation for their interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder and viewfinder cameras such as the M1 (note the lack of a hyphen). It didn't matter that a single letter could not actually be trademarked nor that Olympus was applying this to an S...L...R. Of course, Leica had been dealing with Japanese copycatting for well over 30 years by this point, so their oversensitivity shouldn't have come as a surprise. To rub a little more salt in the wound, they had been taking a royal butt-kicking as far as sales went for nigh-on a decade now from these same manufacturers, particularly when it came to SLRs ;-). Anyhoo, rather than waste time arguing with the wound-up Wetzlarians, Olympus simply acquiesced and renamed the system "OM" on the spot (examples of which started to appear in early-1973) and it seems that they told Leitz that there had only been 5,000 M-1s produced and that they would destroy the rest of the top plates with the M-1 embossing ;-). This feather-unruffling worked, even if the truth was stretched a bit. Olympus had put a lot into M-1 production and they were not about to just trash a bunch of perfectly good parts. So they used up their existing supplies and reserved most of the M-1s for sale in Asia and could still sell 5,000 M-1s in Europe without incurring any further ire from Leitz (remember, this was pre-Internet and globalization was still a twinkle in the eye). M-1 production extended until at least February 1973 (ascertained by date-codes under the film door pressure plates). Whether called M-1 or OM-1, the result was still the same: the camera was the talk of the industry and Olympus proceeded to absolutely bury Leitz when it came to sales (surprise, surprise), which came to approximately 1.5 million copies before the camera was updated as the OM-1N in 1979. For comparison, total Leica SLR production from 1964 - 2009 was around 488,000 (for 13 separate models). And as for their vaunted M-series, Leitz managed to produce just under 52,000 Leica M4, M4-2, M5, and MDa models combined from 1972 - 79. So, Olympus didn't make out too bad with their nice-guy attitude :-). The irony in all of this was Maitani-san's affection for Leica, as his personal camera had been a Leica IIIf, and it was the compact, dense nature of that body and its lenses which inspired his approach to designing a better SLR. For some lemon juice in the papercut for Leitz (who renamed themselves Leica after their most famous product in 1986), we now know that about 52,000 Olympus M-1s (oh my, the irony no longer drips, it is a torrent ;-)) did manage to escape into the wild before the nomenclature change took effect :-o. The OM-1 was intended for professional and advanced amateur use. It was tested for 100,000 shutter actuations (equivalent to the Nikon F & F2 and Canon F-1) in conditions ranging from -20 to +50 Celsius (-4 to +122 Fahrenheit), while reducing weight to 740 grams (26.1 oz) with a 50/1.4 lens mounted versus 1,185 grams (41.8 oz) for the Nikon F Photomic FTN and 1,180 grams (41.6 oz) for the Canon F-1 with their respective 50/1.4 lenses mounted. Initially, the Nikon and Canon models had the advantage of attaching an accessory Motor Drive, but Olympus rectified this in 1974 with the introduction of the OM-1MD (initially, a sticker was added to the front of the camera with a permanent smaller inset plate soon replacing the sticker). Features Unique to the OM-1 Upon Its Introduction Aside from the obvious downsizing and weight-reduction from standard SLRs of the day, the OM-1 introduced some other elemental changes to SLR design that were soon emulated by its competitors:

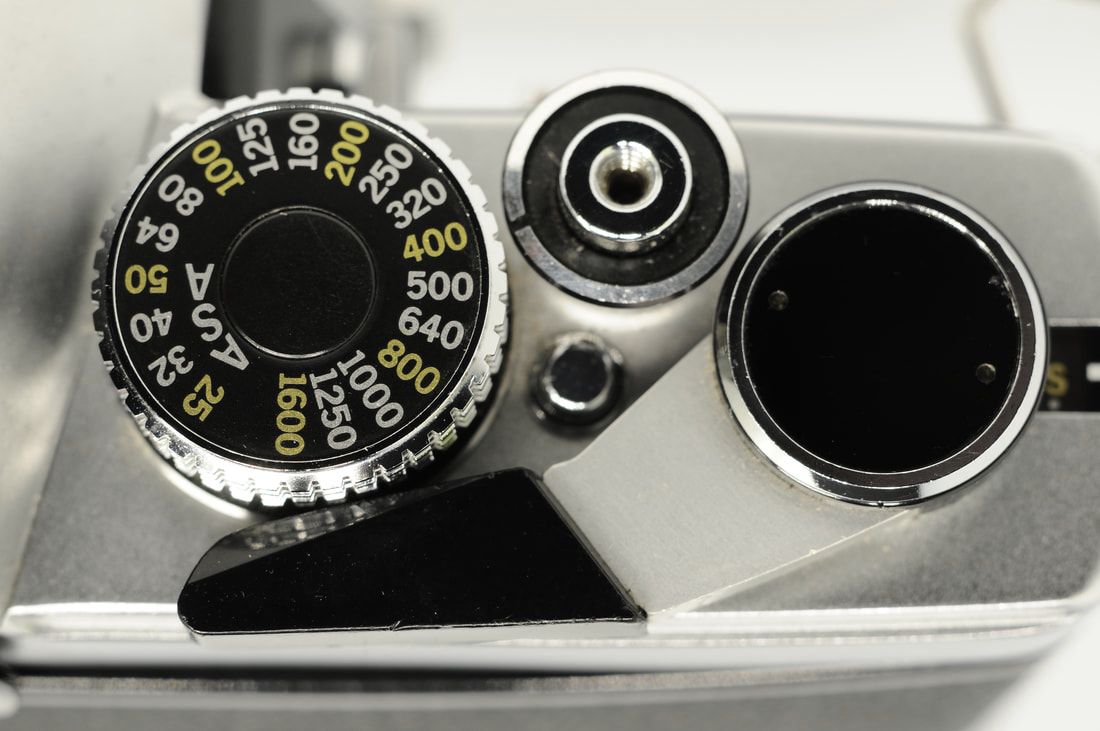

Layout and Handling At a casual first glance from the front, the OM-1 (apart from its size) does not appear to differ much from traditional SLRs as far as control layout is concerned. There is the familiar dial to the left of the film advance lever, with the rewind knob and self-timer lever also in their common locations. But as soon as you hold the camera in your hands and gaze down upon the top deck, you are immediately struck by the strangest set of shutter speed markings from 25 - 1600, with 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1600 marked in yellow on the dial. What the hey?! Then you see three letters on the inside circumference of the dial "A...S...A". Aha! So it's not a shutter speed dial at all...it's the film speed dial (ASA was the precursor to ISO). Almost simultaneously, your left middle finger and thumb have cradled the aperture ring. You now glance at it and...what's that? B, 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, 30, 60, 125, 250, 500, 1000? Have you woken up in some Salvador Dali-themed photographer's nightmare?? Nope, welcome to the shutter speed ring ;-). Want to make a guess for the aperture ring's location? Too late, your left index finger has already found it. So what gives? We have a couple of things to unpack here: 1) optimization of internal space, and 2) Maitani's favored technique for photography.

The location of the film rewind release was another variation from the norm, being easily activated by the right index finger on the front of the camera, instead of fumbling around on the bottom or having to remove a "Never-ready" case to access it. While downsizing was a basic tenet, a deliberate effort was made to keep control sizes as large or even larger than the full-size competition. If you are coming from a traditional Japanese SLR, the OM-1 definitely takes some getting used to. But if you are willing to stick with it and use it the way its designer intended, operation soon becomes instinctive. Yes, there is no display of the set shutter speed or aperture value in the viewfinder, but as your muscle memory builds you begin to intuitively sense the settings. For example, with the two opposed shutter ring gripping surfaces at 3 and 9 o'clock, you know that the shutter speed is set at 1/30 sec. The DOF preview button on the lens falls right into the curve of your left middle finger. The OM-1 rewards repetition. The OM Zuiko focusing ring rubber is one of the grippiest in vintage SLRdom. Olympus developed a fine-grained diamond-pyramidal pattern that grabs your fingertips more securely, with less pressure required, than any other rubber-gripped series of lenses in my experience. As far as the feel of the other controls goes, everything has a feeling of solidity and quality, with maybe the film advance being the only thing that can feel a bit rough compared to such gems as Minolta XEs or XDs, but this can depend a lot on the condition of the particular copy and whether it needs a CLA (clean, lube, adjust). Impact on the Industry At a time when the overall sales of fully-mechanical, manual exposure SLRs were beginning to fall as electronically-controlled Auto Exposure (AE) models were taking off, the OM-1 bucked that trend, averaging sales of nearly 200,000 per year until it received a light refresh to become the OM-1N in 1979. It would continue to be produced in that form until 1987, making for a very successful 15-year run. Olympus positioned it perfectly in the marketplace, with its pricing far below the Canon, Minolta, and Nikon professional models and right in line with their enthusiast-level SLRs, while offering a feature-set distinctly weighted to the pro side. For example, in 1977, Competitive Camera of NYC had the OM-1 with 50/1.4 Zuiko (740 grams/26 oz) priced at $1,135 USD (inflation-adjusted to 2021, as are all prices in this article), with the Motor Drive 1/M.18V Battery Grip & Holder adding $1,445 and 610 grams (21.5 oz) including 12 AA batteries. Compare that to:

Even more than the sales success, it was cases like the Pentax MX that drove home the impact the OM-1 had on the SLR business. By the end of the 1970s, Olympus had pushed their way into the top echelon of Japanese SLR makers, expanding the long-standing "Big 4" into a "Big 5". Bodies and lens lineups throughout the industry were put on diets. The full-size SLR was dead. The OM-1 Today By the time the OM-1N came along in 1979, electronic SLRs had really taken over as far as market share was concerned. Olympus' own OM-2, introduced in 1975, was another success for the company. Even more noticeable was the runaway ascendancy of consumer-targeted electronic SLRs, following the introduction of the Canon AE-1 in 1976. Olympus added their OM-10 to the consumer cornucopia in 1978. The OM-1N found itself superseded in the lineup by the OM-3, Olympus' final pro mechanical SLR offering in 1983, but remained in production until 1987 with the last remnants selling through 1988 for $710 USD (remember that is inflation-adjusted) with a 50/1.4 lens. That was the price of surviving into the Auto Focus (AF) era. Many an OM-1 was relegated to an attic, basement, or closet, pushed aside by all-automatic point & shoots (my Dad referred to them as PhDs - Push here Dummy ;-)), or the latest whiz-bang polycarbonate pretender to the throne. There have been both benefits and consequences from the banishment of these beauties for decades. The benefits being that many low-mileage OM-1s (especially OM-1Ns) are still around, needing only a bit of love to resuscitate them. The biggest problem encountered by potential OM-1(N) (and OM-2(N)) buyers nowadays is the de-silvering of the pentaprism due to deterioration of the foam that Olympus used to "protect" the prism from outside damage. While most full-size SLRs had relied on a rather large air gap between the prism and the outer housing to provide a buffer zone from impacts to prevent prism breakage, with the OM-1 that was out of the question in their desire to reduce bulk. So, their solution was to pack the much-smaller gap with foam to provide a similar level of protection. Which worked fine...until the chemical process of the degradation of the foam would eat the silver coating of the prism. This shows up as grey, green, or black patches in the viewfinder or kind of a wispy or shimmery effect, particularly in the bottom half of the viewfinder. If you are looking at obtaining an OM-1, your first order of business should be to evaluate the viewfinder. Even if it looks good, be prepared to have any existing foam removed (you can DIY or have this done by a repair tech) as it will just be a matter of time before deterioration sets in. Interestingly, on OM-1 bodies with seven-digit serial numbers roughly between 111xxxx - 163xxxx, the foam was deleted from the factory according to John Hermanson, a long-time factory-trained Olympus technician (check out his website www.zuiko.com). With the start of OM-1N production, the foam returned, so you will definitely want to make sure it is removed if you get one. In practice, the foam offered little in the way of additional protection, so you really lose nothing by getting rid of it. Of course, replacement prisms are long-gone now, so the only way to replace a corroded one is to find a donor OM body with a good prism (the same prism was also used on the OM-10, OM-20/OM-G, OM-30/OM-F, and OM-40/OM-PC and they are to be preferred for replacements as none of the consumer models used the foam, according to John) and make the transfer. Here is a video for DIY foam removal: Aside from the foam, the OM-1N or late-production OM-1 bodies are to be preferred. Olympus made 19 internal improvements from the M-1 to the MD version and 15 more over the remainder of OM-1MD production to the OM-1N's debut. The most noticeable changes to the OM-1N were the inclusion of a flash ready & correct flash exposure LED indicator in the viewfinder and a subtly reshaped film advance lever & rewind release button. Other additions included: contacts for databacks, and modified springs in the film door to hold the film cartridge in place more securely. Obviously, your best chance of finding a good prism will be with a late OM-1 and if flash operation is not a big deal for you, you will get nearly all of the other internal improvements that came with the OM-1N. The next issue to be aware of with any OM-1 (or OM-2) is failure of the film to advance completely to the next frame. This stems from a need for a proper CLA of the film advance mechanism. It uses a clutch system that will fail to engage fully if it has suffered contamination or excessive wear. Really, budgeting for a complete CLA is the course of wisdom if you want to get the most enjoyment and life out of any vintage SLR. The OM-1 was designed to be serviced and repaired, it was not throwaway. So a CLA is always worth it, in my mind. Another problem that can be addressed while a CLA is being performed is the meter circuit, which was designed for the 1.35V 625 mercury cell that has been banned for a long time now. A Schottky diode can be installed into the power chain that will properly adjust the voltage for use with the current 1.55V SR44/357 silver oxide cell (with an o-ring installed around its circumference to center it properly in the battery chamber). John Hermanson includes this modification with his standard OM-1 CLA service. An alternative is to use the MR-9 battery adapter (around $30 - $40 USD, nowadays) that uses the smaller 386 silver oxide cell to power the meter. This adapter had a diode integrated in its construction to achieve the same effect as the conversion. The drawback being that the 386 cell has less capacity than the 357 and will thus not last as long. Other than those few niggles, the OM-1 remains one of the finest mechanical SLRs ever to be produced. The combination of compactness, light weight, rugged build, superb viewfinder, responsive controls, and the extensive OM system of lenses and accessories make it a great candidate for beginner or connoisseur, alike. SLRs were never the same after the OM-1, and if that doesn't make it a Game Changer, I guess I don't know what does :-). References: OM-1 @ https://www.olympus-global.com Special Lecture - the OM-1 - the XA Series @ https://www.olympus-global.com The Olympus M-1 Information Page @ http://olympus.dementix.org Olympus OM System - Concepts and Overview @ http://olympus.dementix.org Various Olympus Brochures @ www.pacificrimcamera.com Camtech Photo Services @ www.zuiko.com Leica M Serial #s @ https://cameraquest.com/mtype.htm Leica R-system cameras @ https://www.apotelyt.com/camera-line/leica-r-system Bobby Orr Statistics @ https://www.hockey-reference.com/players/o/orrbo01.html

10 Comments

Mel Jones

5/11/2021 06:35:42 am

Phew ! Gone all misty eyed reading that. The OM1 was my first ever pro camera and what a step up from a tatty Spotmatic it was. Open aperture metering and a viewfinder that was so big it was scary.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

5/12/2021 02:42:56 pm

That's a great story, Mel. It proves there is no substitute for reps with our equipment, even after decades apart :-). I hear you on the lens front, too. While the 50/1.2 is plenty pricey (but about in line with other normal 1.2s from the same era, I am gobsmacked by the ridiculous prices that the 40/2 pancake is getting nowadays. A couple of years ago, I thought it was crazy to see them going for $600 - $800 USD (after all, they were the same price as the 50/1.4 when new), but to see them going for four times that now is just insane! Irony strikes again, I guess. A lot of the f/2 Zuiko glass seems to be going for Leitz-level prices these days ;-) Take care.

Reply

5/21/2021 10:37:02 am

Amazing write up!

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

5/21/2021 11:30:27 am

Hi Robert,

Reply

Peter H

2/6/2023 04:02:31 am

Great article CJ. What a superb little camera. I got converted to them from Canon in the late 80's and never looked back. It was like getting onto a top-class ten-speed racer after a solid steel BMX. Such fantastic light weight and so many great shots to be had with that instant shutter release and no on/off switch. Brilliant. Nowadays we're forced to turn these schmigitals on and off every five minutes and put up with lousy electronic viewfinders that jitter your eyes all over the place...

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

2/6/2023 08:48:45 am

Nice to hear that you are still enjoying your OM-4Tis and that your OM-1s are still providing the same for others, Peter. It's quite rare to hear of anybody switching from OM back to something else once they had made the initial switch during the 35mm era. Your experience seems to bear that out :-). Olympus' accomplishments with the OM system are still impressive, considering the 12-15 year head start the others had when it came to developing their own SLR systems.

Reply

7/25/2023 10:59:58 pm

Overall, this blog has not only educated me about the Olympus OM-1 but also reignited my passion for photography and vintage equipment. Thank you for sharing this wonderful piece!

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

7/25/2023 11:33:54 pm

Glad to hear that you enjoyed the article. Vintage gear isn't everything when it comes to photography, but it can certainly make for a nice change of pace and bring a bit of fun along the way. Thanks for the kind comment :-).

Reply

Les J

6/22/2024 05:36:39 am

Thank you for an extraordinary article. I had an Olympus OM-1 in the 70s, parted with it somewhere/somehow along the road, and bought another one in mint condition 3 months ago. When I picked it up I immediately remembered how it had felt in my hands 50 years ago!! New light seals, CLA'd, and removal of pentaprism foam and it is perfect. I adore my "new" OM-1 and the regrets of losing my old one are now buried. Best SLR ever, no question. Thanks again for a truly great article, much appreciated.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

6/22/2024 06:44:11 pm

Glad you enjoyed the article, Les and congrats on reuniting with the OM-1. Looks like you'll be set for a good long while with this one :-).

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed