|

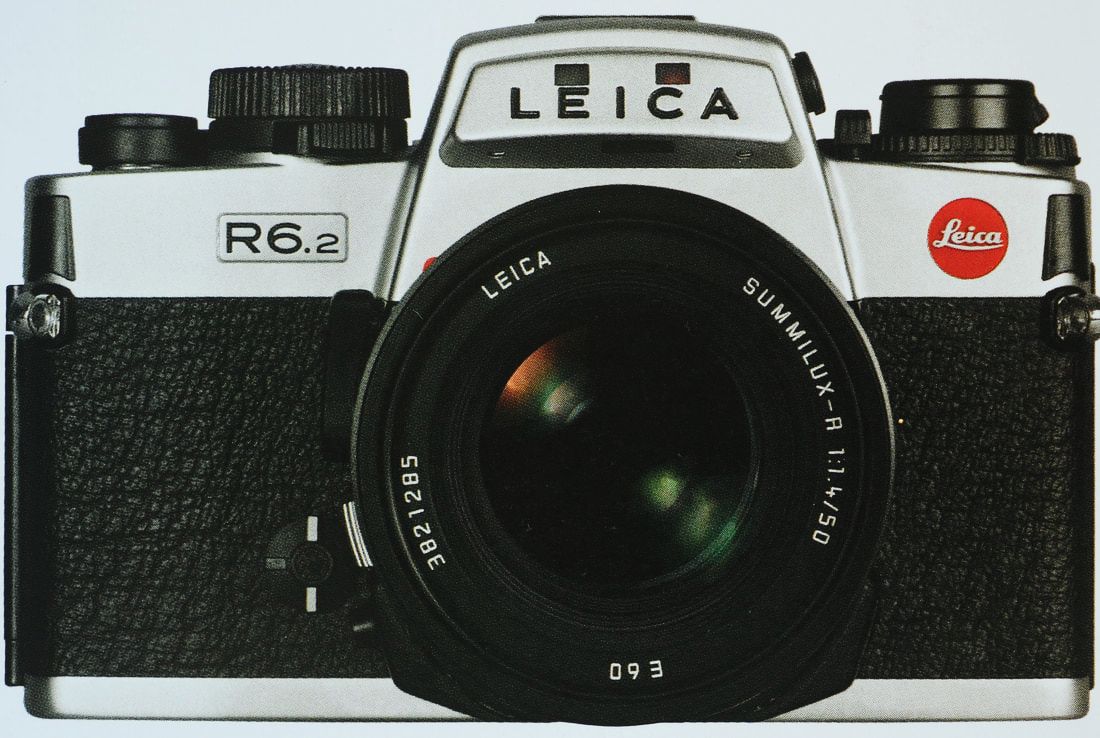

By the time the 1990s rolled around, Auto Focus (AF) 35mm SLRs had become the de facto standard for amateur photogs and were well on their way to domination amongst professionals, too. Manual focus (MF) market share had fallen to less than 10% of total SLR production by 1989. As is common when such market shifts occur, manufacturers will often try to compensate for a loss of sales volume by trying to sell higher-margin products. And so it was in the early-'90s: you had dirt-cheap (often sub-contracted), beginner-targeted MF SLRs on one hand, and a retro-wave of premium manual exposure, mechanical-shuttered models at the other, with the previous mid-level MF models all but abandoned. Ever since the advent of practical auto exposure models, there was a small, but vocal, group of hardcore traditionalists who railed against the constant march of automation & polycarbonization of their beloved SLRs. This niche market may have been small, but to the manufacturers with either zero AF market presence (READ: CONTAX, Leica, Olympus), or a relatively strong base of MF users (READ: Nikon) it was one definitely worth pursuing. This is their story...

22 Comments

Updated Mar. 8, 2024 So where does our fixation with Top Ten Lists come from, anyways? Letterman? The Ten Commandments? Well, if you can't beat 'em.....Here, for your casual perusal, is a chronological consideration of ten important Japanese SLRs that pushed the development of such cameras forward for over 30 years. This is not to say that these are the 10 "top" or "best" SLRs of all time (far be it for me to be the arbiter of such things ;-)), and some may be less familiar than others, but all of them had an undeniable effect on the industry or market as a whole. Let's dive in :-). Updated May 21, 2021 Game Changer. An overused phrase nowadays to be sure, but when applied appropriately it conveys an unmistakable break with the past and an opening up of previously unthought-of possibilities. So it was with the Bobby Orr of SLRs - what came to be called the Olympus OM-1. Bobby Orr??? It's like this, eh. Like Bobby Orr totally changed hockey forever, eh. Like, before Bobby Orr, defensemen didn't lead the rush, eh, or score more than 21 goals a season, eh (he did so for 7 consecutive years, topping out at 46 in 1975), or like score more than 60 points in a season, eh (he scored over 100 for 6 straight years, winning two scoring titles along the way, something no defenseman has done before or since). Or win MVP, eh (three years consecutively, only one other defenseman has won MVP once in the last 50 years). Or win Best Defenseman in the league like eight times in row, eh. And he did all that on like, one knee, eh (his left knee was first seriously injured in his second year in the NHL and he would have 13 or 14 surgeries on it over the course of his career). But his effect on the game was far more pronounced than just the record books. Offensively-minded defensemen (paradox, anyone? ;-)) became indispensable in hockey. Arena construction went nuts in New England as thousands of kids were turned on to hockey by "numbah foah, Bawbee Oah". He turned casual or non-fans into hockey lifers. GAME. CHANGER. In the same era, the Olympus OM-1 did likewise for 35mm SLRs. In this article we will concentrate mostly on the features, operation, and handling of the OM-1 and how it changed the SLR landscape and 35mm photography forever. Today, weathersealing is taken for granted as a common, although not ubiquitous, feature in cameras. Over 30 years ago, however, it was rare in professional SLRs (the Pentax LX being the only model with what would now be considered to be even a modicum of such protection) and non-existent as far as any enthusiast or consumer-level 35mm model went. A plastic bag and some elastics were the standard means of improving the survivability of your rig in the rain or at the beach, with all of the compromises that implies. The time was ripe for innovation. And who better than Olympus to shake things up? Just sit right back and you'll hear a tale, a tale of a fateful slip that happened to three companies who thought they were so hip... In Part 1, we focused on Pentax, Olympus, Nikon, and Minolta, respectively, as the first companies to introduce production auto focus (AF) 35mm SLRs in the early to mid-1980s. Although Pentax was the first-mover (1981), and Olympus & Nikon followed two years later, it was not until the introduction of the trendsetting Minolta 7000 in February 1985 that the AF SLR truly came of age. This was borne out by the other three manufacturers' abrupt decision to adopt Minolta's idea of AF motor-in-body (MIB) design, abandoning their previous allegiance to the motor-in-lens (MIL) philosophy. These companies' next AF SLRs bore an uncanny resemblance to the all-conquering 7000, at least in the lens mount area ;-). Minolta appeared poised to dominate SLR sales for the foreseeable future, yet within three years, they would be toppled from the peak and by the time the early-'90s rolled around, they would be back in their familiar third-place sales position that they had held from the early-'70s onward. So, even being the first successful AF SLR manufacturer was no guarantee of being the long-term winner. How could that happen? This time, we will take a closer look at the reaction to the AF revolution by the then-biggest fish in the SLR pond. I don't know if Rodney Dangerfield was into photography, but if he was he must have used f/3.5 lenses, judging by the way he was always bugging his eyes out. Which would be understandable, because any half-baked photographer knows that f/3.5 is a raging vortex where photons go to die, leaving your eyes straining for the faintest trace of light. Not to mention the utter impossibility of achieving anything remotely resembling shallow depth of field (DOF) with such an infinitesimal iris. No proper lens jockey would be caught dead with such a miserable excuse for a photographic tool. So if you have any remaining shred of photographic self-respect, let me save you the trouble now of reading any further ;-). The 1980s were the heyday of the quality, yet relatively affordable, automatic auto focus (AF) 35mm camera. Competition was intense between manufacturers, and they were constantly trying to leapfrog one another in features and capability. Every year saw some kind of improvement until about 1988 or so, when the inevitable "race to the bottom" really started to heat up. Within this era, the years from 1983 to 1987 were arguably the high-water mark for quality and innovation, and some ingenious engineering. In this article, we are going to key in on a quirky category of cameras that served as a bridge between the original, fixed-focal-length AF point & shoots and the first P&S zooms: the temporary titans of P&S technology..the twin-lens (or bifocal) AFs. Welcome to the final installment of our "Choosing Manual Focus Lenses" series. In this article, we will look at the larger picture of lens sets in general and also check out a few options for specialty optics, such as macros and shift lenses.

Zoom lenses really started to come into their own by the late-1970s and became standard equipment with most SLRs by the mid-'80s. Versatility was the name of the game, with such optics sometimes enabling a photographer to replace up to 3 primes with one lens. However, this was not a free lunch; there were always compromises involved. Welcome to Part 2 of Choosing Manual Focus Lenses. We will now delve deeper into the categories of focal lengths and the differences between them. As in the previous post, we will be looking at this in terms of vintage 35mm format manual focus (MF) lenses, but you can use the principles for more modern glass and other formats. WARNING - There may some numbers involved! (I'll try to control myself ;-)) Fun With Focal Lengths In 35mm format: "Normal" lenses range from 40 - 58mm (with 50mm being by far the most common and was the basic kit lens offered with SLRs for years); Wide-angles go from about 28 - 35mm; Extreme wide angles from 15 - 25mm; Ultra-wide angles are less than 15mm; Telephotos from 65 - 300mm; and Super Telephotos are greater than 300mm. All of these categories are approximate, but you get the general idea. We will look at single focal-lengths and, in the next article, discuss how zooms combine several focal lengths into one lens and the advantages/disadvantages of doing so. One of the most daunting experiences for an SLR owner can be deciding which lenses to choose to achieve their photographic goals. The sheer number of possibilities can seem overwhelming when trying to narrow things down to a manageable kit, both expense- and weight-wise. Further complicating matters is that what works well for someone else may be entirely different than what will be best for you. Choosing lenses goes beyond mere quantitative measurements. Your aesthetic sense of how you see the world around you, along with the genres of photography you pursue, and the conditions you will be working in all have a direct bearing on which lenses will be most suitable for you. Too many of us have learned the hard way about which lenses are best suited to our needs and abilities. Trial and error does often eventually lead us to the right conclusions, but with a considerable amount of wasted time, energy, and MONEY. Could there be a better way? Updated Dec. 1, 2023 Welcome to the fourth installment of our "Choosing a Vintage SLR System" overviews! It features Olympus, one of the most influential Japanese camera manufacturers. We will work our way through: 1) Lenses, 2) Bodies, 3) Flash, 4) Accessories, and 5) Reliability & Servicing. But first...a little introduction :-). Olympus first came to prominence in photography in the late 1950s and early '60s with their half-frame (18x24mm, which was half of the 35mm frame) Pen series of cameras specifically targeted at the Japanese and later, the European markets. They were designed to be affordable for the average worker and economical to operate while still providing decent quality for an 8x10 print. Olympus sold millions of Pens. Ironically, it was the refusal of Kodak to support the half-frame format in the USA that pushed Olympus into the 35mm arena. For a more in-depth look at this turn of events, see this article. Although Olympus was the last of the major Japanese manufacturers to get into the 35mm SLR game, they made quite the splash in 1972 when they finally joined the fray. The immense influence Olympus exerted on the photographic world was due, in large part, to the efforts of the brilliant designer Yoshihisa Maitani and his team of engineers. The creator of the Pen and OM series was always seeking to do something different, not just copy others, and this does much to explain the success of Olympus over a three-decade period with its film-based equipment. The OM series would do more to reduce the size and weight of 35mm SLRs than any other system. What is more interesting was the impact this had on the other, more well-established manufacturers (Canon, Minolta, Nikon, & Pentax) known as the "Big 4". By the late-'70s, that designation had to be changed to the "Big 5", due to the success of the OMs. So let's take a closer look at all the OM system has to offer.  Olympus OM-2 of 1975 Olympus OM-2 of 1975 The impact of a leap in technology is often best measured in the reaction of one's competitors rather than only in market-share or some other basic metric. The Olympus OM series of SLRs are a case in point. While Olympus certainly did grab a nice chunk of market share in the mid 1970's, it was the changes that their fellow manufacturers made in their own designs that define the introduction of the OM-1 as a pivotal point in SLR history. Within five years of the introduction of the mechanical OM-1, followed three years later by the electronic OM-2, the other members of the now Big 5 (Minolta, Pentax, Nikon, and Canon) had all brought out their own downsized and/or lighter-weight models. Five years seems like an eternity in today's marketplace, but back then product cycles normally lasted much longer. Take, for instance, the Pentax Spotmatic. Introduced in 1964, with slight updates in 1971 and 1973, it maintained its layout and dimensions and gained 20 grams of weight until its discontinuation in 1976, 12 years later. The Minolta SR-T 101, which came out in 1966, was produced in the same basic form for 15 years. For over 14 years, the Nikon F hardly changed. Product development also took much longer, without all of the computer modelling and simulation available today. Prototypes were hand-built and tested, and re-built and re-tested many times, before being put into production. So, the fact that within 4 to 5 years these companies all brought out new models, often replacing a full-size model that was only 2 or 3 years old, speaks volumes as to the disruption the OMs caused.  Olympus OM-1 of 1973 Olympus OM-1 of 1973 We have Kodak and Leitz (maker of the Leica) partially to thank for the shrinking of 35mm SLR (single lens reflex) cameras in the 1970s. If it weren't for the obstinacy of the former and the inspiration of the seminal IIIf & M3 models produced by the latter, we may never have seen one of the most influential SLRs in history, whose consequence is still affecting the camera industry. Let's take a trip back to the late 1960s and the birth of the Revolution...you know it's gonna be...all right...all right...all right... |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed