|

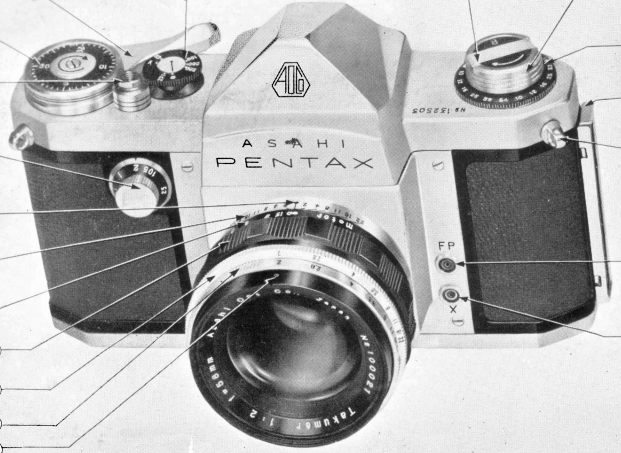

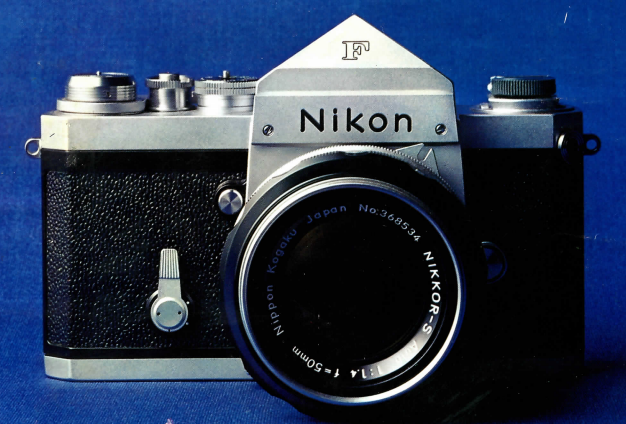

Updated Mar. 8, 2024 So where does our fixation with Top Ten Lists come from, anyways? Letterman? The Ten Commandments? Well, if you can't beat 'em.....Here, for your casual perusal, is a chronological consideration of ten important Japanese SLRs that pushed the development of such cameras forward for over 30 years. This is not to say that these are the 10 "top" or "best" SLRs of all time (far be it for me to be the arbiter of such things ;-)), and some may be less familiar than others, but all of them had an undeniable effect on the industry or market as a whole. Let's dive in :-). Asahi Pentax - 1957 It is hard to overstate the impact of the decision that Asahi Optical Co. made in 1950 to adopt the SLR as its gateway into interchangeable-lens 35mm camera production. Although SLRs had been around for nearly a decade-and-a-half by that time, they were far from mainstream as rangefinders continued to dominate the enthusiast 35mm market post-WWII. The early Asahiflexes were very similar in specification to the Praktiflex of 1938. But they matured quickly...introducing the first instant-return mirror in 1954, then marrying that to a pentaprism finder for an unreversed, upright image in the viewfinder with the Pentax model of 1957, together with rapid-wind film advance and rewind mechanisms. Before the decade was out, Canon, Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta), and Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), among others, would all make the jump to SLRs as their primary 35mm systems. Were there other Japanese SLRs springing up during the mid-'50s? Absolutely. But the basic shape, feel, and control layout of the Pentax would be the most pervasive of any of those early models. Every competitor followed in its footsteps in one way or more. The SLR would be the Japanese vehicle to topple the German camera manufacturers from their hitherto preeminent position in 35mm and the Pentax set the course. Nikon F - 1959 While the Pentax kickstarted the Japanese SLR movement, the Nikon F made it viable among professional photojournalists, the most influential group of 35mm photographers in the latter half of the 20th century. Nikon (and Canon to a lesser extent) first came to the attention of Western PJs in the early-'50s during the Korean War with their superior lenses for the then-dominant Leica and Contax rangefinders. Both companies were also pushing hard during that time to catch Leitz and Zeiss with their own rangefinder designs. By February 1957, Nikon faced a quandary: continue with their very competitive S-Series of rangefinders that had made serious inroads with PJs versus the German competition, or jump on the SLR bandwagon? There was strong debate amongst the Nikon brass about which way to go. Needless to say, the SLR won out, with rangefinder production winding down over the next five years and concluding with two very small final production runs in 1964 to satisfy those hardcore rangefinder PJs that weren't quite ready to move on. Ironically, the F shared a great deal with the final S-Series rangefinders. It could basically be termed as an SP or S3 sans rangefinder and with a pentaprism & mirror box grafted in (just slightly oversimplifying here, but you get the idea ;-)). In fact, the F shared just under 53% of its parts with the SP, making it 47% original :-). The F quickly gained traction with pros in the early 1960's. You soon saw them slung over shoulders and around necks in Vietnam and other global hot spots astride Leica M3s and the like. By the latter part of the decade, the F was the 35mm of choice amongst pros, and one even wheedled its way onboard the late Apollo missions in the early-'70s. The popularity of the F had reached such a pitch by that point that Nikon had to keep it in production for the better part of two years after its successor, the F2, had been released in 1971. Fs have been compared to hammers, anvils, and hockey pucks among other things to describe their rugged resilience in all manner of conditions. And that was (and remains :-)) the number one way into a PJs heart...just get the shot...every time. The F not only elevated Nikon to a 30+ year run as the premier purveyor of professional SLRs, it also made the SLR their default choice of camera system well into the 21st century. Every other major Japanese SLR maker took aim at the F-Series at some point during that period in their efforts to grab some of that notoriety and cachet. During the manual focus era, it would all be for naught. The head start that Nikon got with the F made sure of that. Topcon RE Super - 1962-3 Speaking of taking aim at the Nikon F, we come to another seminal SLR, one that just happened to also be aimed at professionals but introduced a couple of significant features that would eventually be found on even the cheapest consumer-targeted models: the Topcon RE Super. Boasting even finer build quality and equal ruggedness to the Nikon F (and priced accordingly :-)), the RE Super (aka Beseler Topcon Super D in the USA) simultaneously pushed the technological boundaries for SLRs with three features: 1) the first internal through-the-lens (TTL) meter in any production SLR, 2) the ability to do so at full-aperture (meaning that the photographer could focus and meter with a bright viewfinder rather than having to "stop down" the aperture to take the meter reading and then re-open it to focus), and 3) having the aperture mechanisms in the camera and lens automatically "index" or match up with each other. So what was the big deal? These features not only made the RE Super the most advanced, but also the easiest SLR to use when it debuted. Let's take a look at how long it took for the rest of the industry to catch up:

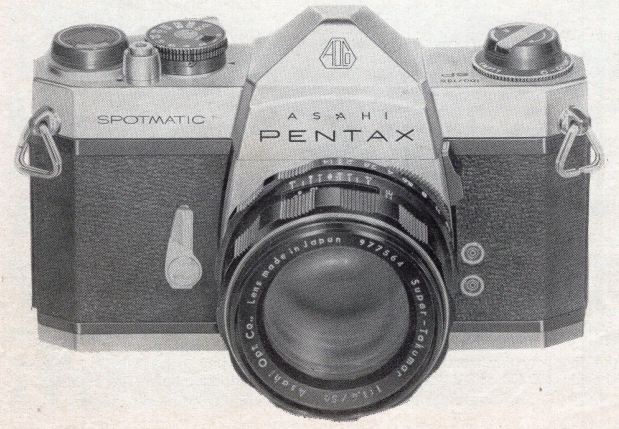

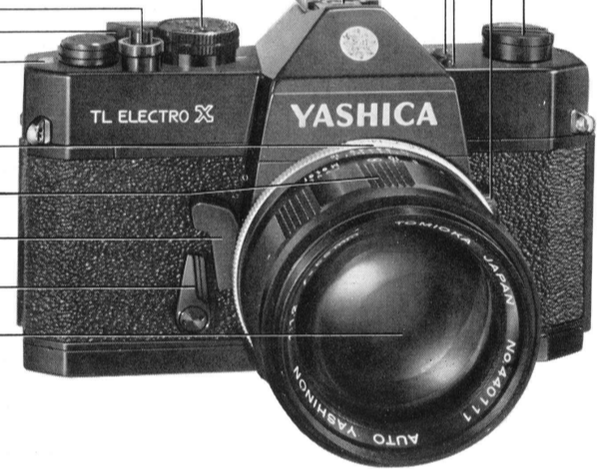

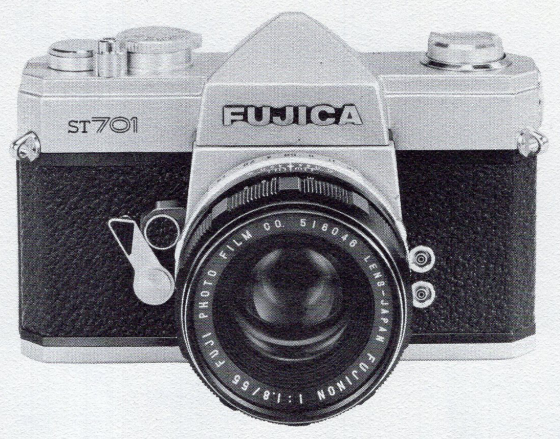

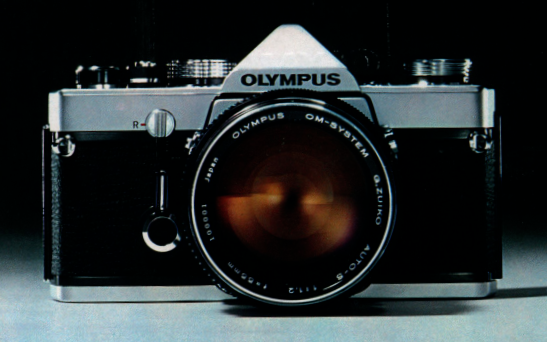

After the RE Super hit the market, there was no going back. You had to at least have TTL in the works if you planned to stick around any longer as a player in SLRland. Admittedly, due to its high level of construction, advanced technology and consequential eye-watering cost, the RE Super was never a best-seller. But when it came to influence, it kept Nikon on their toes, with both the F3 (1980) and F4 (1988) adopting features from a camera at least two generations older. Pretty impressive. And for the millions of other enthusiast and consumer TTL SLRs and DSLRs that followed, the RE Super paved the way. Not too shabby for a camera introduced five years before seat belts became mandatory equipment in motor vehicles in the USA ;-). Pentax Spotmatic - 1964 If the RE Super was first in the race for TTL metering in SLRs, the runner-up Pentax Spotmatic proved to be far more impactful on the market, becoming the first million-selling SLR, ever. Just how much of an impression did the Spottie make? Ok, so Asahi Optical Co., as we saw earlier, was the first-mover in SLRs amongst Japanese manufacturers back in the early-'50s, introducing the Asahiflex in 1952 and really taking a step forward in 1957 with the Pentax. A constant program of incremental improvements netted a total of 15 models prior to the Spotmatic's debut. It took fifteen years for Pentax to reach 1 million total SLRs produced, and that was with the help of Spotmatic sales for two years. With the Spottie just hitting its stride in 1966, it took only three more years for Pentax to sell another million SLRs. So, while the Spotmatic was admittedly not as advanced as the RE Super, it absolutely killed it in sales because it was was less than half the cost while still offering excellent build quality, handling, and capability. The Spottie thus reached a far larger demographic, which was duly reflected in sales and popularity. By the end of SP1000 production in 1977, Pentax had pumped out 5.5 million screwmount SLRs, with various Spotmatic models accounting for the vast majority. The RE Super may have gotten there first and was technologically more advanced, but the Spotmatic took TTL metering mainstream and vaulted the 35mm SLR to the top of the class for serious photo enthusiasts. Yashica TL Electro X - 1968 Three years after Dylan went electric, so did SLRs. While all of our preceding models had their unique attributes and accomplishments, they all had one thing in common: they relied upon the same basic mechanical technology to actuate their shutters that had appeared in its earliest commercial form back in the 1920s. With the Japanese manufacturers rapidly maturing as the leading SLR builders, the push for further automation of the various operations required for exposure of the film went into high gear. The first efforts in this area were in trying to reduce the amount of manual settings requiring input from the photographer. Your three basic settings for exposure revolved around film sensitivity (aka speed), the size of the opening in the lens to allow light through (aperture), and the duration of time that the film would be exposed to light (shutter speed). Until the later-1960's, those three settings were always directly set by the user. Setting the film speed (ASA/ISO) was generally a one-shot deal: you would set it when loading the film and then forget it, whereas aperture and shutter speed would each require setting (or at least checking) for each individual exposure made. But what if you only had to set one of those parameters while the camera automatically set the other one? Wouldn't that be a great time-saver?? And so begat the first Shutter-priority (the user sets the shutter speed and the camera then automatically selects the aperture according to the meter reading) SLRs. Now, Shutter-priority could actually be achieved without electronic assistance or even TTL metering as Konica proved with the aptly-named Auto-Reflex of 1965. But further automation, such as Aperture-priority (user sets the aperture and the camera sets the shutter speed to match the meter reading), or Program (the camera sets both aperture and shutter speed) was going to require electronic intervention. Yashica led the way in the electronification of 35mm cameras during the last half of the 1960s (fittingly, their logo back then consisted of four electrons orbiting a nucleus :-)). The TL Electro X was introduced in late-'68, within months of two German SLRs that were also equipped with electronically-controlled shutters, the Praktica PL electronic and the Contarex SE. While the Germans beat the Yashica to market, neither of them were mature designs and it showed in production and sales: around 6,500 combined for the two electronic Teutonics compared to approximately 300,000 for the TL Electro X over the next six years. While the TL Electro X did not provide any form of auto exposure (it was fully manual exposure all the way) the potentiometer directly linked to the shutter speed dial allowed for intermediate shutter speeds to be set in between the click-stopped standard speeds from 1/30 to 1/1000 of a second. Between 2 sec. and 1/30 sec. there were no click stops and the speed was infinitely variable. This provided more precise control over shutter speeds than any other SLR then available, even the far-pricier Leicaflex SL (which provided intermediate speeds via a mechanical cam system, rather than a potentiometer), and presaged the even finer millisecond-increment control over shutter speeds that the first aperture-priority models would exhibit just three years later. The Yashica also introduced the first electronically-lit viewfinder metering display in an SLR (with miniature red incandescent bulbs). Again, there would be no going back for the industry. Electronic systems would methodically replace mechanical ones in SLRs over the next decade as they offered improved precision, better retained accuracy, and all for less cost as the internal competition amongst the Japanese manufacturers heated up. Ironically, the success of the TL Electro X and its imitators would also serve as the final nails in the coffin of German SLR production, with Zeiss (the makers of the Contarex SE) initiating a 30+ year partnership with Yashica in 1973 to build electronic SLRs for them. Leitz partnered with Minolta in 1972 for the same reasons. While Yashica never was among the top 5 Japanese SLR producers in terms of sales volume, the TL Electro X put them in a position of influence within the industry that they retained well into the 1990s. Fujica ST-701/ST-801 - 1970/1972 Fuji was a late entrant into the SLR business and was never a major player when it came to sales volume. But it would be a mistake to conclude that they had little effect on their competitors. Case in point was their first SLR, the Fujica ST-701, an M42 screwmount body that introduced silicon to SLRs, specifically in the form of the silicon photo diode (SPD) metering cell, which would eventually evolve into the multi-segmented metering systems and even the digital sensors we have today. From the Minolta SR-7 (1962) onward, cadmium sulfide (CdS) metering cells had become industry-standard. The photographic advantages of SPD over CdS was in its greater light sensitivity and responsiveness to changes in light levels. Just two years later, Fuji upgraded the ST-701 with the first light-emitting-diode (LED) viewfinder display in any SLR (along with full-aperture metering) and called it the ST-801. LEDs were not only more rugged and longer-lasting than incandescent bulbs or galvanometers (swinging needles), they also consumed less power for a win-win-win situation. And these LEDs were still nowhere near what we now have as far as efficiency and brightness are concerned. SPDs became the de facto standard metering cells in all but the lowest-grade SLRs within five years and even the cheapest consumer SLRs from the mid-'80s onward all had them. Both SPDs and LEDs were small components, but they had an outsized impact on SLR development, befitting their parentage :-). The ST-701 also was one of the first SLRs to buck the trend of bloat that inevitably had accompanied the evolution of the type as more features were added. For example, the Asahi Pentax had targeted the Leica M3 dimensions and weight as far as the SLR form factor would allow (the Pentax was 7mm wider, 15mm taller, and 16.5mm thicker as a result of having the pentaprism and mirror box assemblies that the rangefinder lacked). Impressively, even with those additions, Asahi managed to bring the Pentax in at 570 grams versus the 580 of the M3. But as time went on, SLRs began to bulk up. The Spotmatic basically maintained the exterior dimensions of the original Pentax with less than a 10% weight gain, but the Nikon F and Topcon RE Super were another story: 860 grams for the Nikon Photomic FTn and 815 grams for the Topcon, making them nearly half again as heavy as the primeval Pentax. Most other SLRs of the 1960s fell in between the Spotmatic and the two professional behemoths, averaging 700-750 grams. The ST-701 was the first sub-600 gram SLR (575 to be precise) since the Pentax S2 of 1962. But the ST-801 would not be able to hold the line, bumping back up to 635 grams. Which meant that there was still room for someone to shake things up further ;-). Olympus OM-1 - 1972 As noted in the previous section, the general trend as far the physical size and weight of SLRs had been going in the wrong direction since the introduction of the Pentax, fifteen years earlier. While the ST-701 had been a considerable step to redress that, it would take an Olympian effort to to push the industry as a whole on an SLR diet. But designer Yoshihisa Maitani would prove equal to the task. Cue the Olympus OM-1. Whereas the Fujica ST-701 tidily beat the original Pentax in width (12mm worth) and virtually equalled it in weight, the OM-1 blasted through the 500-gram barrier (490 to be exact), knocked 9mm off of the width, and 11mm from the height of the original Pentax. That Olympus was able to do this while maintaining full-size controls and a larger, brighter viewfinder was even more impressive. But it was the reaction of the rest of the manufacturers that proved the point: by 1977, the full-size SLR was on life-support, with every SLR builder having introduced compact models to compete with Olympus. But it wasn't just the OM-1 itself; Olympus also trimmed 30-40% from the size and weight of average SLR lenses with their OM Zuikos, setting off another massive round of dieting by their competitors. Prior to the appearance of the OM system, Pentax had prided itself on having the slimmest and trimmest SLRs and lenses. After introducing three new standard-sized K-bodies and 28 accompanying lenses in 1975...only one year later, they brought out two compact M-bodies and their accompanying SMC-M lenses that were clearly targeted to beat, or at least match, Olympus in every dimensional and weight specification. That was unheard of in an industry where normal development cycles were in five and ten year increments. Such was was the game-breaking effect of the Olympus OM-1 :-). Canon AE-1 - 1976 Speaking of 1976 :-), we come to the debut of the AE-1 (Auto Exposure-1) from Canon. Hitherto, auto exposure SLRs were positioned at the top of the SLR makers' lineups (apart, obviously, from professional models ;-)) and priced accordingly. For instance, Canon's EF (1973) commanded a 40% premium over their top enthusiast mechanical SLR, the FTb-N (also 1973) with other manufacturers showing an even greater disparity:

The AE-1 did for Auto Exposure SLRs what the Pentax Spotmatic had done for TTL metering: it broadened access to such cameras to a new type of user. In this case, it was the first-time SLR buyer, who previously was restricted by price point to a bare-bones, de-contented, fully-mechanical, manual exposure model. By substituting electronic systems for mechanical ones as far as then-current technology permitted, and making the greatest use of engineering plastics to date, Canon managed to reduce overall part count by 300 (about 25%). They also were able to automate more of the assembly process. All of this enabled the AE-1 to come in at only a 15% premium over the FTb-N, while offering a marked difference in convenience of use to tyros. Not so coincidentally, the FTb-N was soon discontinued upon the AE-1's introduction and replaced with an AE-1-derived manual exposure model, the AT-1, which allowed Canon again to set a lower price point for such SLRs due to the economies of production and scale that A-body construction allowed. The AE-1 also ushered in the first TV advertisements for SLRs, and Canon masterfully used popular athletes to pitch their latest product. They sold bucketloads of AE-1s as a result. The AE-1 launched the greatest SLR sales boom...ever. Every other player in the SLR game was forced to adopt Canon's approach to the consumer market (even enthusiast/professional stalwart Nikon caved in by 1979 ;-)) and Canon began a run of dominance in interchangeable lens camera sales that has yet to abate, over 45 years after the fact. SLR purists may bemoan the crass commercialism that the AE-1 ignited, but its historical significance is beyond debate. Love it or hate it, the AE-1 did more to make SLRs mainstream than any other model before or since. Minolta 7000 - 1985 So far, we have witnessed a steady progression in the automation of the SLR:

1979-84 saw the first internal-motor film winding and automatic ISO-setting SLRs. That left one major component of SLR operation to be automated: focus. R&D into autofocus (AF) had begun in the mid-1960s, but progress was slow and not of high priority as there was plenty of low(er)-hanging fruit as far as advancements in SLR technology were concerned. Prototypes for AF lenses or cameras would appear at tradeshows occasionally, but they were ponderous beasts that had little appeal due to their bulky motors and other outsized components. By the early 1980s, the continued progress in digital components spurred more development, with Pentax (ME F), Olympus (OM F/OM-30), and Nikon (F3AF) all introducing AF-capable SLRs (provided that they were equipped with a corresponding lens with an AF motor included). While a marked improvement over previous efforts, these systems were still too rudimentary and expensive for widespread market appeal. Coinciding with this was a market bust that started in 1981 as the AE-1-sparked boom finally collapsed. Thus, a meeting of the senior minds of Minolta on June 1, 1981 would prove to be pivotal. At that meeting they were presented by engineers with a prototype the size of a suitcase and were told that it could be made to fit inside a standard-sized SLR body with the latest advancements in microchip technology. Minolta had just released the manual focus X-700 to go up against Canon's revamped AE-1 Program and sales were brisk, but Hideo Tashima (son of the founder of Minolta, Kazuo Tashima) realized that it was on the tail end of one era of technology and that to be competitive in the future, a major step needed to be taken and he pushed for going ahead with AF SLR development. This decision would prove to be the right one. Compact AF 35mm cameras were becoming the flavour du jour with consumers and rapidly eroding the market for consumer-level manual focus SLRs. There was a 24% drop in market share for SLRs as a whole from 1981 to 1984. The industry was desperate for a shot in the arm and, in February 1985, Minolta provided it. The Minolta 7000 was the first practical, affordable AF SLR, and it came complete as a system with a dozen initially-available lenses (that grew to nearly 30 over the next three years) to choose from (the previously-mentioned AF models had no more than three, and usually only one AF-compatible lens, at best) and other common accessories from the get go. Crucially, these lenses were no larger, heavier, or more expensive than their MF counterparts, due to Minolta's decision to have the drive motor installed in the camera body rather than the lens, which ran counter to the prevailing philosophy of motor-in-lens held by virtually all of their competitors. The result was comparable to a bomb blast for the rest of the industry:

Without the Minolta 7000, the SLR sales slide would have resembled a cliff-drop in 1985 and '86. It single-handedly caused the entire industry to pivot, much as the Spotmatic and AE-1 had in the 1960s and '70s, respectively. In modern parlance, the Minolta 7000 was a game changer. AF would be the last major development in film SLRs prior to the digital era...or would it? Canon T90 - 1986 Okay, so AF was the last major internal technological development in the evolution of the 35mm SLR. But there was one last pivotal advancement made only a year after the Minolta 7000 appeared that has survived to this day on the latest interchangeable lens cameras and that will likely only die with them: external controls. The Canon T90 took a control concept as old as 35mm still photography itself (Oscar Barnack's dial), married it to late-1970's push buttons (thank you Pentax ME super ;-)), and the elemental '80s LCD to complete the SLR development cycle. The resulting Button + Dial + LCD control interface completely took over by the mid-'90s. The T90 became as seminal to the next three decades of successive SLR control layouts as the original Pentax had been 30 years earlier. Ironically, the camera sold relatively poorly, because it lacked one critical feature for a new SLR in 1986...AF. But, only three years later, when the Canon EOS-1 debuted, the circle was completed; Canon married their Minolta 7000-motivated EOS project to the Luigi Colani-designed T90 and set the stage for their displacement of the Nikon F system as the choice of professionals during the 1990s. Wrap-Up So there you have it. Ten very influential SLRs. Some may have more name recognition or current cachet than others, but all of them pushed the evolution of the type and stirred their competitors to keep pressing to at least catch up to, if not surpass the others. Were they the only noteworthy ones? Of course not, there were many other contributions to the refinement of the SLR into the dominant enthusiast camera of the last half of the 20th century. But that will have to be a future consideration :-).

References: The Definitive Asahi Pentax Collector's Guide 1952-1977 by Gerjan van Oosten Various Nikon F Brochures and Manuals @ www.pacificrimcamera.com The Nikon Journal #26 - Dec. 31, 1989 "Debut of Nikon F" @ Nikon Camera Chronicle Nikon - A Celebration (3rd Edition 2018) - Brian Long Various Topcon RE Super Brochures and Manuals @ www.pacificrimcamera.com Phot Argus Topcon Super D Test, Nov. 1969 @ Pacific Rim Camera Debut of Nikon F2 @ https://imaging.nikon.com/history/chronicle/history-f2 Debut of Nikon F3 @ https://imaging.nikon.com/history/chronicle/history-f3 Pentax: 1964 -1976: The Spotmatic @ http://www.pentax-slr.com/71760549 Asahi Pentax Spotmatic - 1964 @ http://basepath.com/Photography/Spotmatic.php Phot Argus Yashica TL Electro X Test, Mar. 1969 @ Pacific Rim Camera Fujica ST-701/-801 Manuals and Brochures OM-1 @ https://www.olympus-global.com Special Lecture - the OM-1 - the XA Series @ https://www.olympus-global.com The Olympus M-1 Information Page @ http://olympus.dementix.org Olympus OM System - Concepts and Overview @ http://olympus.dementix.org Various Olympus Brochures @ www.pacificrimcamera.com Canon Camera Museum: History Hall 1976-86 Canon Camera Museum: Camera Hall Film Cameras AE-1 My Bridge to America: Discovering the New World for Minolta - Sam Kusumoto Canon Camera Museum - Camera Hall: T90 A Design Revolution The T90 SLR Camera

4 Comments

I bet you and I could argue into the small wee hours on this topic :)

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

8/19/2022 11:24:00 am

Hello again, Mel. No need for diplomacy ;-). I am not claiming that these ten cameras are "the most" influential, just that they were integral to the evolution of the SLR. There is plenty of room for discussion on this subject, and that was really part of the point of it. Arbitrarily restricting "best of" or "the most" lists to ten is laughable from my standpoint. And my idea of what was influential or not about any subject will necessarily will be different is one way or another from yours or anyone else's. Nothing wrong with that in the least. I could have easily upset my tidy list of ten by going to 11 with the Konica FS-1, or any number of other noteworthy candidates ;-). So feel free to share your picks. Best regards.

Reply

Melvin Bramley

1/5/2023 06:16:13 pm

Olympus OM1 for its viewfinder and overall size.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

1/7/2023 09:09:16 am

Way to rock it old school, Melvin :-).

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed