|

Regular visitors to this site may have noticed a bit of a trend: As much as we love the classics, we also have a thing for "sleepers", those anti-Instygrammy, tacky Tik-Tok-immune cameras that do one thing: take great pictures ;-). And if you are looking to dabble in a bit of film, but don't feel like auctioning off a body part or two to look all the business, here is yet another option to consider... Although they came late to the 35mm Auto Focus (AF) SLR party in 1987 (trailing Minolta by just over two years, and Nikon by 11 months), when Canon debuted their EOS 650 (March 1987) and EOS 620 (May 1987) models, they rapidly closed the gap to their two main competitors. Within two months of its introduction, the EOS 650 became the best-selling 35mm SLR in Japan and Europe. The 650 was easily a match, technologically, for its main competitors: the Minolta 7000 and Nikon N2020 (F-501 outside North America). When combined with Canon's decade-long lead in marketing prowess, it was a recipe for success. However, Canon's initial delay in the AF market meant that they would not have their second-generation EOS models ready until 1990, while both Minolta and Nikon would both introduce theirs in 1988. As with any new technology, the improvements in early generations are markedly larger than in later ones. And so it was with AF SLRs. The Minolta 7000i and Nikon N8008 (F-801 outside North America) were massive leaps from their forebears and vaulted both back ahead of Canon in the AF techno-battle. How would Canon respond?

0 Comments

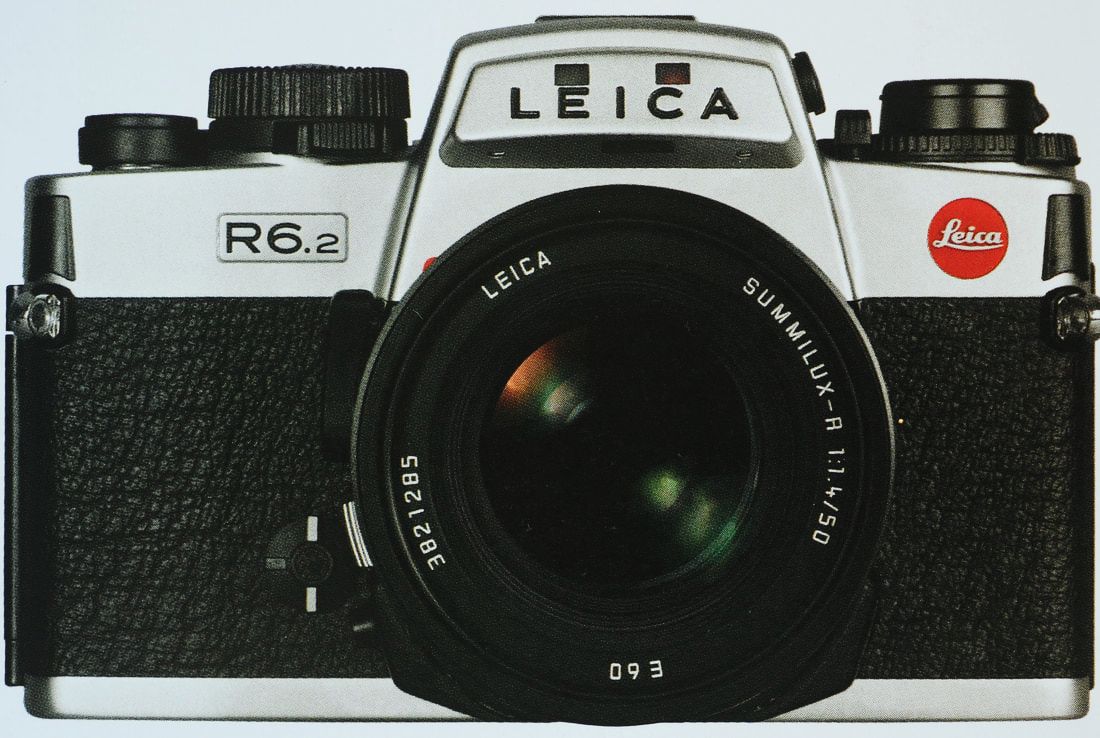

By the time the 1990s rolled around, Auto Focus (AF) 35mm SLRs had become the de facto standard for amateur photogs and were well on their way to domination amongst professionals, too. Manual focus (MF) market share had fallen to less than 10% of total SLR production by 1989. As is common when such market shifts occur, manufacturers will often try to compensate for a loss of sales volume by trying to sell higher-margin products. And so it was in the early-'90s: you had dirt-cheap (often sub-contracted), beginner-targeted MF SLRs on one hand, and a retro-wave of premium manual exposure, mechanical-shuttered models at the other, with the previous mid-level MF models all but abandoned. Ever since the advent of practical auto exposure models, there was a small, but vocal, group of hardcore traditionalists who railed against the constant march of automation & polycarbonization of their beloved SLRs. This niche market may have been small, but to the manufacturers with either zero AF market presence (READ: CONTAX, Leica, Olympus), or a relatively strong base of MF users (READ: Nikon) it was one definitely worth pursuing. This is their story... Updated May 2, 2023 Three decades...Six (and-a-half ;-)) models...ONE platform. Approximately 4.5 million bodies sold. That makes the compact enthusiast/semi-professional manual focus line of Nikon SLRs the longest-lived chassis in the history of the marque, and arguably, the most successful. Spurred on somewhat by the success of the Olympus OM bodies but mostly by the groundbreaking Canon AE-1, Nikon's foray into the world of compact SLRs first bore fruit in 1977 with the FM, and ended up with an "old vines" distillation of body and flavor with the FM3A in 2001. But there was a lot of ground covered between those bookends. So which one will be right for you? Let's dig in :-) Updated Nov. 3, 2021 In an earlier article, we looked at the differences between the Nikon F3 & F4 and how they might affect your purchase and/or usage of either body. Not being able to leave well enough alone, I thought, "seeing as you can purchase an excellent F2 Photomic or Photomic A or a plain F3 for $250 - $300 USD, what if we tried the same sort of comparison between the F2 and F3?" I mean, what could possibly go wrong in attempting a dispassionate, objective analysis of two excellent SLRs made by Nikon? Oh...right...we are dealing with two groups of people: 1) those that believe that the SLR reached perfection in 1971 and everything since is an abomination against the laws of nature, aka "Knights of the Order of F2" (referred to henceforth as KOTOOF2), and 2) everyone else. ...waits 5 seconds... Okay...now that the pitchforks, torches, burning effigies, and other accoutrements to a rational discussion are at hand, let's wind the clock back to 1980 and the seismic shift that occurred in the Kingdom of F. Updated July 23, 2020 PROGRAM...the buzzword for SLRs in the early 1980's. Only with this technological breakthrough could photographers now surmount the barrier of having to think about camera settings and composition at the same time! Freedom from Aperture- or Shutter-priority or (heaven forbid you were still using) m...mm...mmm...Manual exposure beckoned. At last, focus (no pun intended) only on composition...unencumbered by such banalities...and our wunderkamera will do it all better than you ever could, anyways...(Okay, okay, that's enough...1980's marketing-speak now set to OFF). Riiight. Anyhoo, Program was going to be the next big thing to save the Japanese manufacturers from the the slippery slope of the latest SLR sales slide (Aside: it didn't ;-)). From the introduction of the Canon A-1 (1978), the first proper Program mode SLR (along with the three more familiar exposure modes mentioned above), to the 1985 introduction of the real "next big thing" (Auto Focus), the profligate proliferation of Program SLRs only accelerated. Followers included: Fujica's AX-5 (1979), Canon's AE-1 Program (1981) & T50 & T70 (1983 & '84), Minolta's X-700 (1981), Nikon's FG & FA (1982 & '83), Olympus' OM-2S & OM-PC/OM-40 (1984 & '85) , Ricoh's XR-P (1983), Yashica's FX-103 Program & the Contax 159MM (1985), and the two subjects of this article: the Pentax Super Program (1983) and Program Plus (1984). That's 16 models within seven years. So what set the Pentaxes apart from the rest of their competitors? Read on at your leisure ;-). The 1980s were the heyday of the quality, yet relatively affordable, automatic auto focus (AF) 35mm camera. Competition was intense between manufacturers, and they were constantly trying to leapfrog one another in features and capability. Every year saw some kind of improvement until about 1988 or so, when the inevitable "race to the bottom" really started to heat up. Within this era, the years from 1983 to 1987 were arguably the high-water mark for quality and innovation, and some ingenious engineering. In this article, we are going to key in on a quirky category of cameras that served as a bridge between the original, fixed-focal-length AF point & shoots and the first P&S zooms: the temporary titans of P&S technology..the twin-lens (or bifocal) AFs. Updated Mar. 8, 2024 Coming-of-age. If any term could be applied to Nikon's auto focus SLRs from 1986 to 1991, that one has to be at the top of the list. The transition to AF maturity coincided with Nikon's rise to second place in the overall SLR market to essentially form a duopoly with Canon as the other members of the then-Big 5 (Minolta, Olympus, and Pentax) slid further and further behind, and in Olympus' case, dropped AF SLRs completely. The irony in all of this was that Minolta had gotten the drop on everyone and dominated the first few years in AF SLR sales with their groundbreaking 7000 model. Canon brought out their T80 FD-mount SLR a couple of months after the 7000, and it wasn't even close to the Minolta. So much so, that Canon abandoned further FD-mount AF development and began a crash program to come up with a completely new mount and SLR system. It would be two years before they brought out the EOS 650. For Canon, that would turn out to be time well spent, as the EOS cameras rocketed them to AF SLR sales leadership in rather short order. Nikon got on the board in April of 1986 (over a year after the 7000 made its not-so-subtle entrance). While the F-501 did not surpass the 7000, it was the first true competitor to the Minolta and gave Nikon a toehold (and critically, a one-year head-start over Canon to get established in the market) until they could bring out their second generation enthusiast AF SLR in 1988. By the mid-'90s Nikon had clawed their way past Minolta and tried to maintain pace with Canon in market share (which didn't happen, but they did comfortably establish themselves in second place :-)). Let the retrospecting begin... Updated June 30, 2021 Welcome to our second system overview, this time featuring the Canon FL/FD system, in our "Choosing a Vintage SLR System" series. Following a brief introduction we will break things down via the format of 1) Lenses, 2) Bodies, 3) Flash, 4) Accessories, and 5) Reliability & Servicing. Canon was an early entrant into the SLR market in 1959 (the same year as Nikon) with its Canonflex model in what it called the R-mount. Compared to its competitors Asahi Optical Co. (Pentax), Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta), and Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Canon got off to a slower start in SLRs as far as sales went. This was due to a couple of factors: 1) Canon remained focused on the rangefinder market as the others went pretty much all-in on SLRs, and 2) the Flex and its immediate descendants the RP, and R2000 were quirky machines with a bottom plate-mounted film advance trigger which was rangefinder-derived. The R-mount, with its breech lock lens coupling, did serve as the basis for the succeeding FL and FD mounts, although it used different internal controls for aperture functions. With the final R-mount camera, the heavyweight RM (1962), Canon went more mainstream with the control configuration and it was their first SLR with a built-in meter. They still remained fourth in sales, however, because they trailed the other three manufacturers in camera/lens automation. Updated Aug. 30, 2021 In 1962, Nikon decided to take the plunge into the amateur enthusiast SLR market with a new model, the Nikkorex F. From 1959 to this point, they only had the solitary, professional-oriented, Nikon F in their SLR lineup. The price of the F put it out of reach of the average 35mm photo enthusiast. In the meantime, Minolta and Pentax were cleaning up in the sales department in the amateur market, with Pentax having approximately four times and Minolta ten times the overall sales of Nikon in the whole interchangeable lens SLR market in 1962. This would prove to be a very consequential decision by Nikon, one that would impact their growth for decades to come. And not just in camera body sales. However, the Nikkorex F would fail to achieve Nikon's goal of successfully breaking into the enthusiast market. So it was back to the old drawing board... "Endling" - an individual that is the last of its species. -The journal Nature- Updated Feb. 6, 2021 Meet the last great manual focus Minolta...the XD (XD 11 in North America/XD 7 in Europe). Steady on, now! Wasn't the X-700 (1981) an award-winning camera with a more extensive and capable system of accessories?! Yes...yes it was, and it sold very well (2.1 million copies versus 750,000 XDs)...and lived a much longer life...and it has TTL flash...and a real motor drive...yadda, yadda, yadda. Just pick up an example of each and stroke the film advance lever. Case closed. Well, not really closed...I'm just getting warmed up ;-). Now the objective of this article is not to denigrate the X-700. (That would be rather unappreciative, seeing as it was my first real camera, it got me hooked on photography, and it is a good camera.) But a funny thing happened when I was looking for a backup body, back in 2000. I chanced upon a black XD 11 at my local pusher...I mean camera store, and for $50 less than I had paid for the X-700! Fast forward 16 years, and the 11 is still with me while the X-700 was sent down the road a few years back. Why? Minolta was one of the most successful SLR manufacturers throughout the 1960s. With their SR and SRT series of cameras and Rokkor lenses they were consistently among the top 2 in SLR sales by the Big 4. (Pentax was the other market leader. Canon and Nikon were the two junior members as far as sales went.) They had sold more than 400,000 SLRs per year from 1966 through 1970. Nevertheless, they (as did the other members of the Big 4) realized that the market for fully-mechanical, manual-exposure SLRs was starting to reach a saturation point. And competition between the Japanese companies was heating up now that they had collectively pushed the German camera makers into irrelevance in the SLR market. Electronically-controlled SLRs would be the new weapons in the battle for market supremacy during the 1970s. The Big 4 had all begun development of these in the mid-'60s and now the fruitage of that labour began to appear: the Pentax Electro Spotmatic & ES (1971); the Nikkormat EL (1972); and the Canon EF (1973). Although Minolta would be the last to introduce their challenger in 1974, the XE-7 (XE-1 in Europe & XE in Japan) would turn out to be the best-seller among these first-generation electronic SLRs.

Updated May 20, 2021 $250 - $350 USD. That's what it takes to have one of these beauties for your own nowadays (2020). For those of us who couldn't afford to own a pro-level camera back when the F3 & F4 were current, now is a golden opportunity to obtain a little slice of photographic history that is as usable as ever. If you have ever picked up one after holding a consumer-level body, there is simply no comparison (Yeah, they are that solid & heavy! Especially the F4! :-)). Even with F3 values rising again (and at a faster rate than the F4's), it still comes down to the attributes most important to you, the individual photographer, when making a choice between the two (if you can't have both, that is ;-)). It is the objective of this article to clearly delineate the differences between the F3 and F4 that could influence your decision-making process. So here we go... |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed