|

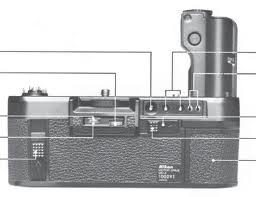

Updated Jan. 7, 2022 In 1976, Nikon found itself at a crossroads with its F-series of professional bodies. The F2 was at the peak of its domination of the market, with 125,000 sold in that year, the greatest annual total achieved by a single F model ever. Compare that to 36,000 Canon F-1s and around 8,000 Minolta XK/-1/Ms and clearly Nikon was sitting pretty with the mighty, mechanical F2. The problem was in coming up with its successor, the F3. The reason for this struggle was that Nikon had to try and balance its desire to make significant strides with the F3 and yet not alienate its customer base of professionals, a group not known for rapid acceptance of change ;-). Especially change involving more reliance upon electronics (where are you going to get batteries in the middle of a fire-fight in the jungle, or what happens if you miss a deadline because of a dead camera?). So here was the challenge: Maintain high reliability and quality while: 1) incorporating automatic operation, 2) making the camera easier and cheaper to build, and 3) convincing pros that it was worth upgrading to. Nothing to it, right? So how did Nikon do? And is the F3 for you? An Electronic F - Skating on Thin Ice? Nikon had begun development of the F2's heir in 1973, initially taking an evolutionary approach. They basically attempted to make an electronically-controlled F2 (otherwise known as HERESY to any F or F2 wielding pro ;-)) using analog ICs (integrated circuits). The engineers came to the realization that there was going to be too much information for these ICs to carry without enlarging the camera excessively. They had also decided to include electromagnetic shutter release, to use an electronic quartz-timed shutter, and to use an LCD (liquid crystal display) readout in the viewfinder instead of the LED (light-emitting diode) displays then current. They had made some progress in these areas, but two revolutionary products from other camera makers soon made their impact felt on the design team. The Olympus OM-1 of 1973 had major ramifications for the size and weight of SLRs in general, and the F3 designers felt the need to reduce size and weight from the F2. This was going to be impossible, however, with the analog ICs requiring too much physical space. So the program stalled for a time. But with the release of the digitally-controlled, microprocessor-powered Canon AE-1 (1976), the engineers found the answer to this dilemma. They could now use the advantages of digital circuitry to meet the first two challenges mentioned above: automate certain camera operations & simplify construction while reducing the size and cost of the F3.  DE-2 Finder w/ "P" Screen DE-2 Finder w/ "P" Screen Another decision the development team made was to move the metering cells from the finder to the body. This was a major change in design philosophy for Nikon, as from the Nikon F Photomic (1962) onward, metering cells were built-in to the Photomic interchangeable finders. The problem that this presented was that for finders without metering cells, such as the waist-level and 6x high-magnification finders, no TTL (through the lens) metering was possible. The engineers wanted the F3 to be able to offer TTL metering no matter which finder was used, thereby increasing the versatility and convenience of the camera. Moving the metering in-body also enabled TTL flash metering, and no longer was any exposure compensation required for different focusing screens or finders. The F3 would eventually have 8 different finders and 20 focusing screens available for virtually every situation. This change also allowed for a reduction in size and weight of the finders, which contributed to the overall downsizing of the camera by 4mm in width, 6mm in height, and by 140 grams of weight compared to the F2.  MD-4 Motor Drive MD-4 Motor Drive One of the distinguishing features of the F-series cameras had long been their motor-drive capability. (Indeed, this had probably been one the most important factors in Nikon's subsequent domination of the pro market.) With each generation, motor-drive performance had been improved and usability increased. With the MD-4 for the F3, Nikon was able to set a new standard for ergonomics, accuracy, speed, and energy efficiency. It would be another feature, however, that did much to ease the transition for professionals to a battery-dependent camera. Cleverly, the engineers designed the MD-4 so that it would power not only film advance/rewind, but the F3 itself. Since the vast majority of photojournalists and action photographers used motor drives, and carried batteries to power them, this required no change to their routines and enabled the 2 internal 1.55V button cells installed in the F3 to be used as a backup power source. The MD-4 is able to expose up to 140 36-exposure rolls on one set of 8 AA alkalines while powering the camera, too. To put that in perspective, consider the figures for the closest competitor to the F3 - the Canon New F-1 - with its FN Motor Drive using 12 AA alkalines: just 50 36-exposure rolls with 180 grams more weight! The comparison with the MD-4's predecessor the MD-2/MB-2 (the F2 motor drive with an 8-AA battery pack) is even more jarring: only 30 rolls of 36 exposures per set of alkaline batteries and with a slower maximum speed of 2.5 fps (frames per second; without mirror-lock-up) versus the F3's 3.8 fps (also without MLU). That's more than 4 times the battery life! So the performance was there under the hood. But, what about the styling? Wait a minute! Since when did styling have anything to do with a Nikon??!! Nikon's were supposed to get the shot no matter what, with no frills, and maybe stop a bullet in the process! We don't need no steeenkin' styling!!! The beauty is in the function, not the form rant, rant, rave, rave!!!! Ok...easy boy...just relax...easy there now...just take a breath...that's it. Could it just be possible to have both? Enter the thin red line... An international product like a Nikon camera should have an international design. Kazuhiko Mitsumoto - Automotive photojounalist There was one other factor that led to the redesign of the F3 from its original conception. Kazuhiko Mitsumoto was an automotive journalist and also a photographer who used Nikons. He happened to know one of the greatest automobile designers of the 20th century, Giorgetto Giugiaro. Mitsumoto-san would introduce Giugiaro to Nikon in the mid-1970's and would set off a collaboration that would last well into the 21st century. Nikon cameras would never look the same. And it all began with one thin red vertical line :-).  The "Bold" F3 Grip The "Bold" F3 Grip The thin red line is appropriate, seeing as it neatly delineated the break from the traditional design of the F2 towards the definitely more modern-looking F3 which had (GASP!!) actual curves ("hedonism!", cries the purist). Popular Photography, in its April, 1981 Lab Test of the F3 called the grip design "bold". To the purist the thin red line symbolizes the fall of Nikon into unforgivable sin (electronics, automation, plastics, batteries, batteries, and more batteries. "Curse you, Niiikonnnn!!...") from which it has never recovered. And that blasted red line has become like some sinister, amorphous mass that changes shape with each new Nikon model, and just when you hope it has been banished...there it comes again, and now smiling so insolently at you! Mr. Giugiaro knowingly spoke of people's emotions being stirred by the appearance of their cameras. It appears that the F3's styling was so effective that it can stir the emotions of its detractors to a pitch of extreme intensity ;-). For anybody else, the red line can at turns be elegant, stylish, or invisible (particularly behind the MD-4 motor drive or the photographer's right hand, just in case you are using your F3 for surveillance. (Well-played, Giugiaro.) So it would seem, that in actual use, the thin red line has little to no impact on the capability of the camera. Its effect appears to be entirely psychological. So how did this new direction for the F3 affect sales? While Nikon likes to say that the F3 was embraced immediately by pros, the truth is a little more complicated than that. Some pros never did make the switch, feeling that there were just too many compromises in an electronic camera over a mechanical one. Others took a "wait and see" attitude, deciding to let others be the beta-testers ('guinea pigs' in '80s-speak) of the camera. And, finally, there were some early adopters who were willing to take the chance that Nikon hadn't completely lost its mind. Introduced in March of 1980, the F3 sold between 35 - 40,000 copies in 9 months. Not bad, but compared to the 60,000 F2s sold in 1979, and 10 - 12,000 F2s in 1980 up to and concurrent with the F3's introduction, it seems clear that acceptance was far from unanimous. Also demonstrating the resistance of the market was the fact that Nikon priced the F3 lower than the remaining F2s to provide incentive to buyers to choose the F3. Nikon could afford to do so because of the savings they had made in partially automating F3 production over the completely hand-built F2. And the market did come around to the F3. Sales doubled in 1981, and reached 100,000 + in 1982 and 1983 and remained above 50,000 annually until 1988. The F3 stayed in production for over 20 years, eventually selling over 790,000 copies. Which was longer than any other F-series Nikon, and it survived the introduction of two successors. Why? Because even with all of the initial hubbub about the automation of the camera, it was still very simple in layout and operation (and downright primitive next to to the F4 & F5), and was reliable enough to remain the choice of many a pro or serious amateur. For pros, it comes down to whether you get the shot or not, and evidently the F3 got enough shots to remain, by far, the best-selling professional camera of the 1980s. But Is the F3 for You? Today, you can pick up a nice F3 for around $250 USD (update: more like $300 - $350 USD in mid-2020 ;-)). A sweet deal, especially when you compare it to the prices of new ones in the 1980s. Check out some inflation-adjusted prices (2016) for F3 and F3HP bodies from specific years:

70% depreciation definitely makes for a buyer's market :-). But cost should be the least of your considerations when considering an F3. After all, there are plenty of excellent vintage SLRs at or below this price range. So what can make or break an F3 for you? Here is a short questionnaire (tongue only slightly in-cheek):

If you answered "yes" to all four bullets, congratulations, you are perfectly suited for an F3! A more in-depth buyer's guide-style look at the features of the F3 (in comparison with the F4, which is still available for around $250 US these days) can be found here. But if you really do want a simple, uber-reliable camera with pro-level build quality without modern pro-level pricing, the F3 is very, very tough to beat. And drop dead gorgeous with that thin red line. ;-) References:

Debut of Nikon F3 @ www.imaging.nikon/history/chronicle The Story of the Nikon F3 @ www.imaging.nikon/history/chronicle Nikon F3 & Nikon F3 serial numbers @ www.nicovandijk.net Nikon F3 @ Photography in Malaysia Nikon Production Numbers @ Knippsen virtual camera and photo museum Lab Report: Top of line Nikon F3. Popular Photography, p. 111, April 1981 Historical Cameras: Nikon F3 April 2007, Shutterbug magazine Nikon F3 User Manual @ http://cdn-10.nikon-cdn.com/pdf/manuals/archive/F3.pdf Nikon MD-4 Manual & picture credit @ www.butkus.org Nikon - A Celebration (Third Edition) by Brian Long

2 Comments

Hi there,

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

9/24/2022 10:34:53 am

Nice to hear that you enjoyed it, James. Sorry for the late reply as your comment was misfiled somehow. I find I have similar experiences with the F3...I end up with a few more keepers than average. It just works :-). Take care.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed