In this same poetic sense, there are truly creative individuals who can find limitless nuances of light and color within a single blossom. These are true artists even if they've never held a paintbrush in their hand or drawn a single line. These are the souls endowed with the innate gift of being able to see with a Renoir's eyes. Whew!! You've got to hand it to the ad agency for CONTAX in the early-1990s; they came up with some doozies. Now, it's Advertising 101 to hype your product, but not even Leica dared to push it as far in their ads of the time ;-). Nothing like buttering up your potential customers by comparing them to an Impressionist master (eyeroll). By comparison, when they introduced the ST two years later, they were slightly more subdued, if only when referring to the potential users of this "extra" perfect camera:

4 Comments

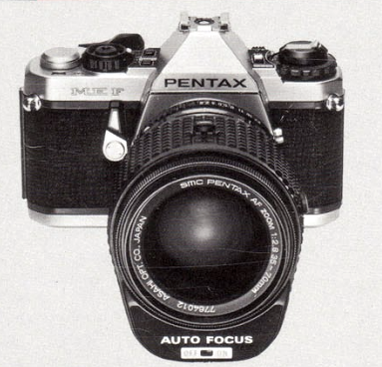

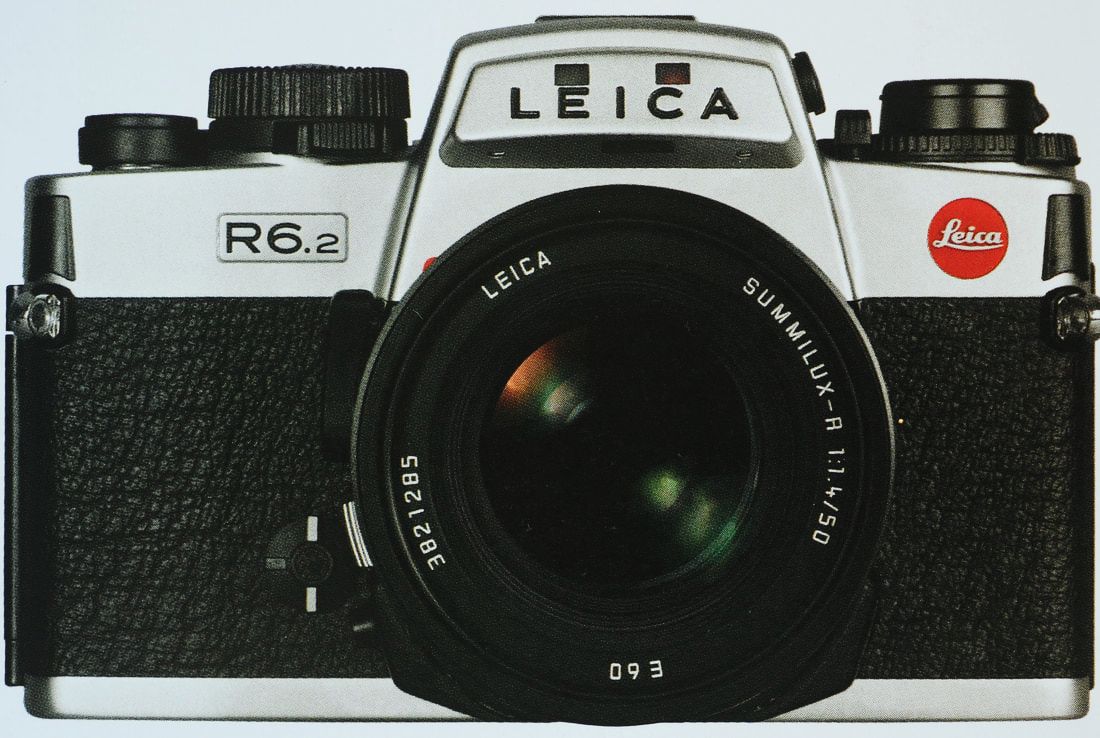

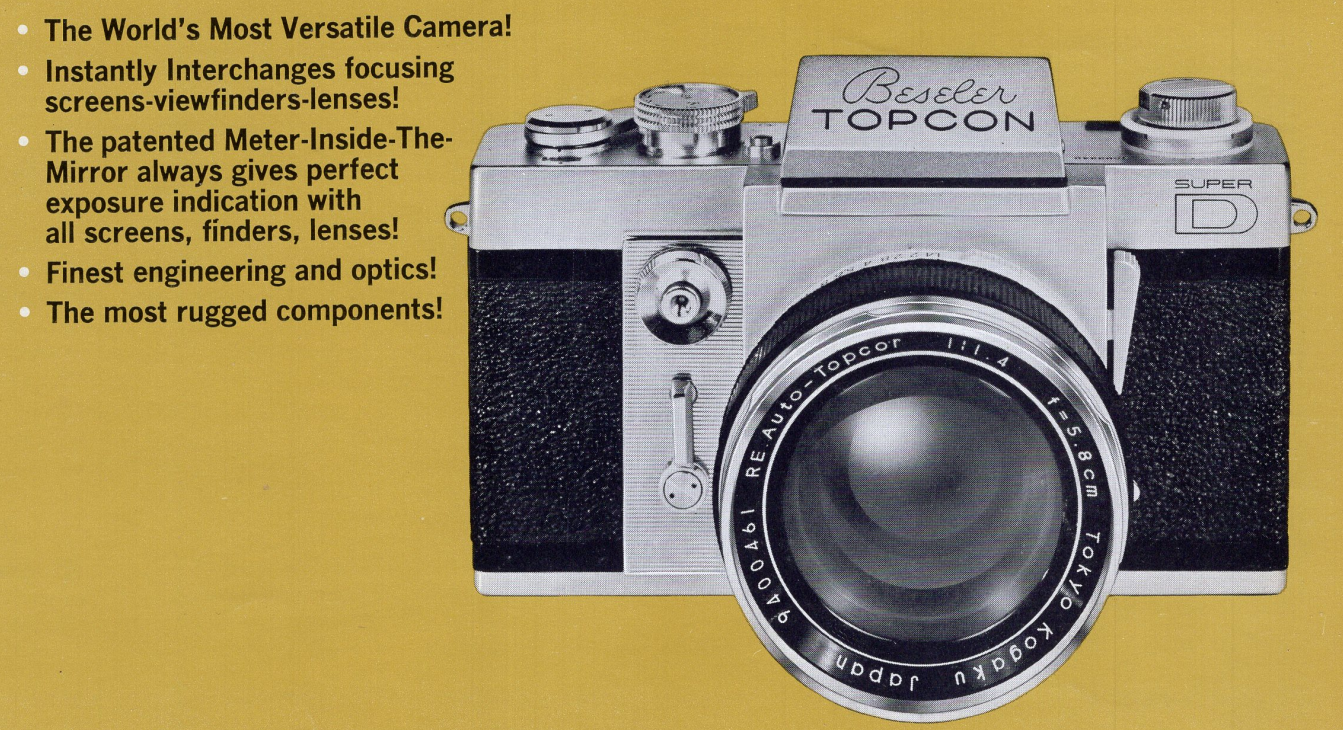

The 58mm focal length is inextricably tied to the introduction of the 35mm SLR in the mid-1930s. This was due entirely to the physical difference in construction required by the mirror (the "reflex" part of the Single Lens Reflex designation) used for viewing the subject directly through the lens versus the then-standard rangefinder design. Because of the greater depth including the mirror in the optical path required, this entailed more distance between the rear of the mounted lens and the film plane, which is termed "back focus". The longer back focus of the SLR meant that the standard 50mm focal length rangefinder lenses of the day could not bring the rear focus node to the proper distance from the film plane if simply converted to the SLR mount (in this case, the Kine Exakta of 1936). By the mid-1960s, 50mm would become the standard for SLR lenses as optical designers were able to gradually overcome the design challenges presented by the SLR. In the meantime, the easiest way to overcome the back focus issue was to simply bump the focal length a bit to accommodate the extra back focus. And that is what Willy Merte of Zeiss did in developing the famous 58mm f/2 Biotar, released in 1938. The Biotar would set the bar for standard SLR lenses for the next 25 years, famously duplicated in the Helios 44-2, among others. Most manufacturers of SLR lenses followed Merte's lead by producing 55 to 58mm lenses, particularly for faster-than-f/2 maximum apertures. Minolta was no exception, and would, in fact, be the last holdout among the Japanese manufacturers when it came to adopting 50mm as its normal lens focal length. They introduced their fast 58/1.4 only three years after their first SLR, the SR-2, and supplemented it with a 58/1.2 seven years later. The 58/1.4 would remain in production until 1973, and the 58/1.2 until 1978, with both being replaced by 50mm lenses, accordingly. This is their story. Updated May 29, 2024 When Canon management decided on March 31, 1985 to embark on a two-year program to develop a completely clean-sheet auto focus (AF) 35mm SLR system, they were granting Minolta a two-year head-start in that burgeoning market. This was a result of the instantaneous success of the Minolta 7000, introduced almost two months before. Canon realized that their first FD-mount AF SLR, the T80, due to be introduced in April of that year, was completely outclassed by the 7000 and bold measures were thus imperative. Consequently, Minolta had the 35mm AF SLR market to itself for 14 months, until Nikon introduced their F-501 (N2020 in USA) in April 1986. Right on schedule, in time for their 50th anniversary as a camera manufacturer, Canon brought out the EOS 650 on March 1, 1987. Within two months, it became the top-selling AF SLR in Japan and Europe and was a match and more for the 7000 and F-501. But Minolta had not been sitting idly by. The summer of 1988 brought their second-generation enthusiast AF SLR, the Minolta 7000i, which was a huge jump forward from its not-exactly-ancient ancestor, as is usually the case in the early stages of the growth cycle of any technology. Canon had caught up to (and surpassed in a few areas) Minolta's and Nikon's first-gen AF SLRs, but how would the second generation of EOS fare against a much more sophisticated competitor? Middle-of-the-road. Middle-child-syndrome. When it comes to lenses you would be hard-pressed to find another optical specification that seemingly fits either of those epithets more closely than a plain ol' 200mm f/4 prime. A middling focal length, a middling maximum aperture, middling size and weight, and no optical development for almost fifty years...all of these added together must up to a middling "meh" experience. Or do they? Could it be that this valedictorian of the Class of the Overlooked is actually an overachiever and more than the sum of its moderate specifications? Well, you will have to decide that for yourself :-). Yes, it's been a long time in coming, but we will now resume our "Choosing a Vintage SLR System" series. Previous articles delved into the Big 5's (Canon, Minolta, Nikon, Olympus, and Pentax) manual focus (MF) 35mm SLR ecosystems, breaking them down into five main sections: 1) Lenses, 2) Bodies, 3) Flash, 4) Accessories, 5) Reliability & Servicing. We will now start digging into a series of smaller Japanese manufacturers that, while perhaps not as well-known nor heralded, were certainly influential in the industry and can offer interesting alternatives to the Big 5 in your search for an SLR system. We (re)start with CONTAX/Yashica, a collaboration between Zeiss and Yashica. As before, we will confine our consideration to the MF system, which is where C/Y made their greatest mark (their Auto Focus or AF system, unfortunately, never amounted to much, in spite of a promising R&D program in the early-'80s). Regular visitors to this site may have noticed a bit of a trend: As much as we love the classics, we also have a thing for "sleepers", those anti-Instygrammy, tacky Tik-Tok-immune cameras that do one thing: take great pictures ;-). And if you are looking to dabble in a bit of film, but don't feel like auctioning off a body part or two to look all the business, here is yet another option to consider... Although they came late to the 35mm Auto Focus (AF) SLR party in 1987 (trailing Minolta by just over two years, and Nikon by 11 months), when Canon debuted their EOS 650 (March 1987) and EOS 620 (May 1987) models, they rapidly closed the gap to their two main competitors. Within two months of its introduction, the EOS 650 became the best-selling 35mm SLR in Japan and Europe. The 650 was easily a match, technologically, for its main competitors: the Minolta 7000 and Nikon N2020 (F-501 outside North America). When combined with Canon's decade-long lead in marketing prowess, it was a recipe for success. However, Canon's initial delay in the AF market meant that they would not have their second-generation EOS models ready until 1990, while both Minolta and Nikon would both introduce theirs in 1988. As with any new technology, the improvements in early generations are markedly larger than in later ones. And so it was with AF SLRs. The Minolta 7000i and Nikon N8008 (F-801 outside North America) were massive leaps from their forebears and vaulted both back ahead of Canon in the AF techno-battle. How would Canon respond? By the time the 1990s rolled around, Auto Focus (AF) 35mm SLRs had become the de facto standard for amateur photogs and were well on their way to domination amongst professionals, too. Manual focus (MF) market share had fallen to less than 10% of total SLR production by 1989. As is common when such market shifts occur, manufacturers will often try to compensate for a loss of sales volume by trying to sell higher-margin products. And so it was in the early-'90s: you had dirt-cheap (often sub-contracted), beginner-targeted MF SLRs on one hand, and a retro-wave of premium manual exposure, mechanical-shuttered models at the other, with the previous mid-level MF models all but abandoned. Ever since the advent of practical auto exposure models, there was a small, but vocal, group of hardcore traditionalists who railed against the constant march of automation & polycarbonization of their beloved SLRs. This niche market may have been small, but to the manufacturers with either zero AF market presence (READ: CONTAX, Leica, Olympus), or a relatively strong base of MF users (READ: Nikon) it was one definitely worth pursuing. This is their story... If the Minolta MD Rokkor-X 100/2.5 we looked at previously is the definition of a sleeper, the subject of this post is anything but. I feel quite safe in postulating that there has been more virtual ink spilled over the Nikkor 105/2.5 (in all its guises) than any other medium (75-105mm) telephoto of the vintage 35mm era :-). Well, let's spill a little more, but hopefully we will cover some fresh territory in the process and see why Nikon kept this lens design all the way to the end of the film era in the early 21st century and why it remains one of the best performance-to-price ratio vintage lenses you can lay your hands on today :-). Updated Apr. 4, 2024 From its inception in late-1958, the Minolta SR system included at least one short telephoto of 100mm focal length, predating their first 85mm optic by over a decade. The last listing at B&H that I could find for the final New MD 100/2.5 iteration was from July 1994 (production had obviously ended back in the mid-'80s when the Alpha/Maxxum AF mount was introduced). So a successful (albeit fairly quiet) 35-year sales run in total for the manual focus Minolta 100mms. And yet, when talk turns to short Minolta manual focus (MF) telephotos, almost invariably, the 85/1.7 (first introduced in MC Rokkor form in 1970) tends to dominate the conversation. Not without reason, mind you; the 85/1.7 and its successor, the 85/2, are some of the finest examples of the type, regardless of brand. As a result, the 100s have slipped into the shadows somewhat. But they are definitely worth your consideration...so let's dive in. Updated Mar. 8, 2024 So where does our fixation with Top Ten Lists come from, anyways? Letterman? The Ten Commandments? Well, if you can't beat 'em.....Here, for your casual perusal, is a chronological consideration of ten important Japanese SLRs that pushed the development of such cameras forward for over 30 years. This is not to say that these are the 10 "top" or "best" SLRs of all time (far be it for me to be the arbiter of such things ;-)), and some may be less familiar than others, but all of them had an undeniable effect on the industry or market as a whole. Let's dive in :-).  1981 saw some major technological milestones: the first manned orbital mission of the Space Shuttle...the debut of IBM's Personal Computer (aka the PC)...the first flight of Boeing's second-gen wide-body, the 767...and the first Delorean DMC-12s began to roll off the line in Ireland. In step with such advancements, Pentax sought to push the technological boundaries of the 35mm SLR, much as they had a decade earlier with their Electro Spotmatic (ES) aperture priority autoexposure model. Only this time it was focus rather than exposure that they were seeking to automate. In late-'81, the ME F would become the first production 35mm auto focus (AF) SLR (with a caveat ;-)) to hit the scene. Updated Jan. 10, 2023 Although Canon was not the first to the 35mm lens-shutter AF (auto focus) party with their Sure Shot (aka AF35M in Europe, aka Autoboy in Japan) model, with it they did introduce the auto focus technology that would come to dominate that burgeoning market until digital came on the scene. Not to mention, the Sure Shot was the first compact 35mm to combine AF with automated film winding and rewinding at the push of a button, i.e. the first proper Point & Shoot. The Sure Shots would go on to be the most commercially successful P&S lineup for the next 25 years. Updated Mar. 8, 2024 As the purveyor of choice for professional SLRs for over three decades, it shouldn't come as a surprise that Nikon was among the more conservative of manufacturers. After all, most professionals in any field are inclined to stick with the tried-and-true over any newfangled gee-whizzery that comes along. Case in point: the original F lasted in production for 14 years, the whippersnapper F2 for 9, and the last bastion of manual focus pro Nikons, the F3, stuck around for 21 years. Likewise, the enthusiast-targeted FM/FE/FA platform barely changed in layout (a couple of minor control changes from the original FM to FE in 1978, and in the final FM3A model of 2001 being the biggest modifications) in nearly a quarter-century of production. So when Nikon did make major design changes, even in their non-professional models, it was a...big...deal. The summer of 1988 brought such a change, the DNA of which has managed to leapfrog from the venerable F-mount (in both film and digital forms) to the latest Z-mount mirrorless models. Worst of all for Nikonistas, it originally came from C...C...C...Canon (aaauuuggghhh!!!). Updated June 21, 2024 It is common knowledge among Nikonistas that the Series E line of lenses are unworthy of the Nikkor designation, due to the copious amounts of "plaaaastic" in their construction and their intended audience of wet-behind-the-ears beginner hacks (the only thing worse than "plaaaastic" to a Nikonista is a "baaaattery", always uttered with head reared back and clenched fists shaking at the heavens). Even having "Nikon" engraved on these "re-badged third party" lenses went way too far for these gatekeepers. Seeing as the little EM consumer SLR that the E lenses were designed for deservedly "failed" on the market (selling a paltry 400,000+ units in its first full year of worldwide distribution and "only" 1.5 million in less than 5 years overall) it should come as no surprise that the Series E line of lenses turned out to be one of Nikon's greatest blunders. Read on to see how they barely survived and the lessons they learned (or rather, failed to learn ;-)). Updated Jan. 20, 2023 1957. A year of events that would reverberate for years to come. Sputnik. The debut of cable TV in the USA. "I Love Lucy" ended production. The Cat in the Hat was published. And a musical duo that would be as influential as anyone on the next two decades' of popular music (the Beach Boys, Beatles, and Bee Gees were only a few among the many that would cite themselves as being significantly impacted by them) had their first #1 hit: 1957 would also see the introduction of the first 35mm SLR from a relatively small Japanese manufacturer that was to have an outsized influence on the industry that would continue for over thirty years. In that year, TOPCON (Tokyo Kogaku) would find themselves at the leading edge of 35mm SLR technology and they would remain there for the next decade. The 1960s would see them emerge as Nikon's (Nippon Kogaku) most serious competitor in the professional 35mm SLR market. By 1977, however, Topcon's photography division would be a shell of its former self, outsourcing its remaining SLR production and diving right to the bottom of the market. By 1981 (with Nikon owning over 75% of the pro market), Topcon was out of the 35mm business completely, even though they live on to this day in the industrial and medical optics arenas. So, what happened? How did Topcon go from industry leader to also-ran in the space of a generation? Updated July 23, 2020 PROGRAM...the buzzword for SLRs in the early 1980's. Only with this technological breakthrough could photographers now surmount the barrier of having to think about camera settings and composition at the same time! Freedom from Aperture- or Shutter-priority or (heaven forbid you were still using) m...mm...mmm...Manual exposure beckoned. At last, focus (no pun intended) only on composition...unencumbered by such banalities...and our wunderkamera will do it all better than you ever could, anyways...(Okay, okay, that's enough...1980's marketing-speak now set to OFF). Riiight. Anyhoo, Program was going to be the next big thing to save the Japanese manufacturers from the the slippery slope of the latest SLR sales slide (Aside: it didn't ;-)). From the introduction of the Canon A-1 (1978), the first proper Program mode SLR (along with the three more familiar exposure modes mentioned above), to the 1985 introduction of the real "next big thing" (Auto Focus), the profligate proliferation of Program SLRs only accelerated. Followers included: Fujica's AX-5 (1979), Canon's AE-1 Program (1981) & T50 & T70 (1983 & '84), Minolta's X-700 (1981), Nikon's FG & FA (1982 & '83), Olympus' OM-2S & OM-PC/OM-40 (1984 & '85) , Ricoh's XR-P (1983), Yashica's FX-103 Program & the Contax 159MM (1985), and the two subjects of this article: the Pentax Super Program (1983) and Program Plus (1984). That's 16 models within seven years. So what set the Pentaxes apart from the rest of their competitors? Read on at your leisure ;-). In the first two parts (Part 1 & Part 2) of this series, a recurring cycle of market saturation and obsolescence as the drivers of the Japanese camera industry for the past five decades was clearly seen. The manufacturers relied upon a series of technological advances and clever marketing to combat these repetitive downturns. And as long as they remained the providers of such advances, their position as the standard-bearers of photographic capability remained secure. But in this 21st century, a major disruption has taken place, one that the Japanese camera companies collectively and individually failed to anticipate. Before we look at the magnitude of this disruption and its eventual outcome, let's briefly look at how things have gotten to this point. Updated June 18, 2022 In our previous article, we started searching for a possible precedent in the film SLR era for today's sea-change in the digital (and DSLR, in particular) age. Is Canon president Fujio Mitarai's forecast of a possible 50% reduction in digital camera sales within the next two years overly pessimistic? (UPDATE: As it turned out the decline from 2018 to 2020 came to 55%, so no it wasn't :-)) Sigma Corporation president Kazuto Yamaki's recent comparison of the current state of transition from DSLRs to Mirrorless ILCs (Interchangeable Lens Cameras) with the MF to AF SLR transition of the late-'80s begs further investigation. So, just how quickly did the transition from manual focus (MF) to auto focus (AF) SLRs as far as market dominance actually take in the late-1980's? Before we answer that, let's identify our Cast of Corresponding Characters. Updated June 18, 2022 "plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose" - Jean-Baptisite Alphonse Karr c. 1849 or as it is commonly rendered en Anglais: "the more things change, the more they stay the same" As of the spring of 2019, this maxim still rings true in the photographic equipment world (and the larger world in general :-)). ***FAIR WARNING*** - This series of articles contains numbers (please, no), history (bleccch!), and eventually, analysis (make it stop!). 678 Vintage Cameras cannot be held responsible for drowsiness, general lethargy or any other sleep-inducing effects should you choose to continue. Parallels are about to be drawn between the digital and film eras, which will be an immediate turnoff for adherents of the "either/or" crowd, and therefore an utter and complete waste of such a person's time. (As opposed to the standard waste of a person's time that this space traditionally occupies ;-)) Now that we've got that out of the way (is it too early in the spring for crickets to be out and about?), let's see how a 170-year-old saying relates to events in the camera industry today. In this first portion, we will look at the present state of affairs and some underlying factors, and Part 2 will deal with the breathtaking details of the Auto Focus revolution of the 1980s. (I swear I keep hearing crickets...) Today, weathersealing is taken for granted as a common, although not ubiquitous, feature in cameras. Over 30 years ago, however, it was rare in professional SLRs (the Pentax LX being the only model with what would now be considered to be even a modicum of such protection) and non-existent as far as any enthusiast or consumer-level 35mm model went. A plastic bag and some elastics were the standard means of improving the survivability of your rig in the rain or at the beach, with all of the compromises that implies. The time was ripe for innovation. And who better than Olympus to shake things up? In the manual focus (MF) era, the XD was arguably Minolta's biggest step forward technologically. It was the first 35mm SLR to feature both aperture- and shutter-priority auto exposure modes and all within the flanks of the first compact Minolta SLR body. The new form factor and added electronic sophistication necessitated the adoption of integrated circuits (ICs) by Minolta. The XD was thus far more complex electronically than its predecessor, the XE, which did have an electronically-controlled shutter and aperture-priority, but was still largely mechanical in its actual operation. The XD's basic electronic layout would prove to be the pattern for all subsequent manual focus Minoltas (including the XG and X-xxx series). And it was the XD that made capacitors front and central in the basic operation of the mirror and shutter assemblies of every succeeding Minolta MF SLR. Capacitor failures are few and far between with XDs and the majority of XGs, but became much more prevalent with the X-xxx series. My personal X-700 fell victim to "capacitor-itis" almost 20 years ago, but my XD 11 has never skipped a beat. That set me to wondering... Updated Sept. 13, 2021 Canon the innovator...Canon the boundary pusher...Canon the...wait just a minute! Are we talking about the same Canon that moves today at what appears to be a less-than-glacial pace? Nope, we are talking about the Canon of over three decades ago...the vintage Canon ;-). A Canon that, while still the market leader, was determined to meet a declining SLR market with more than retrenchment. From an all-time peak of nearly 7.7 million SLRs sold in 1981, by 1983 sales for all brands of SLRs had fallen by over 30%. Sound familiar DSLR users? Canon had wrung the last drops from their A-series of SLRs (1976-84), the most successful line of manual focus SLRs ever, and the catalyst to the SLR boom of 1976-81. The question now facing Canon (along with very other SLR maker) was: Where to go from here? Their first response would be the T-series of SLRs (1983-1990). So how did that work out for them? From a sales perspective, the T-series failed to accomplish Canon's goal of revitalizing the SLR market. Each model seemed bedeviled by at least one Achilles' heel. But one thing was for certain, the problems came down to execution and timing, not a lackadaisical attitude on Canon's part. And ironically, out of the (relative) failures of the T-series would come Canon's greatest period of success, the seeds of which were sown by the most tragic of the Ts...the T90. Just sit right back and you'll hear a tale, a tale of a fateful slip that happened to three companies who thought they were so hip... In Part 1, we focused on Pentax, Olympus, Nikon, and Minolta, respectively, as the first companies to introduce production auto focus (AF) 35mm SLRs in the early to mid-1980s. Although Pentax was the first-mover (1981), and Olympus & Nikon followed two years later, it was not until the introduction of the trendsetting Minolta 7000 in February 1985 that the AF SLR truly came of age. This was borne out by the other three manufacturers' abrupt decision to adopt Minolta's idea of AF motor-in-body (MIB) design, abandoning their previous allegiance to the motor-in-lens (MIL) philosophy. These companies' next AF SLRs bore an uncanny resemblance to the all-conquering 7000, at least in the lens mount area ;-). Minolta appeared poised to dominate SLR sales for the foreseeable future, yet within three years, they would be toppled from the peak and by the time the early-'90s rolled around, they would be back in their familiar third-place sales position that they had held from the early-'70s onward. So, even being the first successful AF SLR manufacturer was no guarantee of being the long-term winner. How could that happen? This time, we will take a closer look at the reaction to the AF revolution by the then-biggest fish in the SLR pond. Updated May 2, 2022 In the land of manual focus SLRs circa 1984, things were looking grim. That old implacable foe, "market saturation", had once again surfaced from the depths of the eastern Pacific to wreak havoc on the sales charts of the Japanese manufacturers. Over a decade had elapsed since its previous appearance in the early to mid-'70s. The proliferation of affordable autoexposure SLRs, from 1976 onwards, had not only blunted that attack, but had then led to the greatest sales extravaganza for 35mm SLRs, EVER. But now, the denizen of the deep was back with a vengeance and taking names. Internal motors for film advance, LCD displays, and angular '80s styling were doing nothing to stem the tide. Only another big-time innovation was going to give the SLR makers a chance. Their trump card? The 1980s were the heyday of the quality, yet relatively affordable, automatic auto focus (AF) 35mm camera. Competition was intense between manufacturers, and they were constantly trying to leapfrog one another in features and capability. Every year saw some kind of improvement until about 1988 or so, when the inevitable "race to the bottom" really started to heat up. Within this era, the years from 1983 to 1987 were arguably the high-water mark for quality and innovation, and some ingenious engineering. In this article, we are going to key in on a quirky category of cameras that served as a bridge between the original, fixed-focal-length AF point & shoots and the first P&S zooms: the temporary titans of P&S technology..the twin-lens (or bifocal) AFs. |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed