|

Middle-of-the-road. Middle-child-syndrome. When it comes to lenses you would be hard-pressed to find another optical specification that seemingly fits either of those epithets more closely than a plain ol' 200mm f/4 prime. A middling focal length, a middling maximum aperture, middling size and weight, and no optical development for almost fifty years...all of these added together must up to a middling "meh" experience. Or do they? Could it be that this valedictorian of the Class of the Overlooked is actually an overachiever and more than the sum of its moderate specifications? Well, you will have to decide that for yourself :-). Before we get too far, let me be the first to say that a 200/4 is not for everyone. Nor is any other focal length/aperture combination, for that matter. If you are a 24/28mm...50/58mm...100/105mm...and so on type of person, a 200/4 fits the focal length progression quite nicely. But, if you are more of the 35/85/135mm-type, it likely will not be enough of a jump from the 135 to make carrying one worthwhile. Most people also find manually focusing a lens with an f/4 maximum aperture and a split-image focusing aid to be a challenge. The solution: using the microprism collar or matte field aids in your SLR viewfinder instead. Of course, that does not work for everyone, either, due to each individual's particular eyesight situation. The trick is to figure out whether a 200/4 will match up with your personal capabilities and limitations. The nice thing is that values have bottomed out, so you can try one and then move it along for at least what you paid for it if it doesn't work out for you. Now, while we will be diving in with the 200/4 Nikkors specifically, the same principles will apply to virtually any Japanese OEM 200/4 from the mid-'70s era, when development of these lenses peaked. Hopefully, you will find this helpful in deciding whether or not to fall down the 200/4 rabbit hole, small as it may be. We are talking f/4, after all, where photons go to die ;-). Origins The market for 200mm lenses basically coincided with the rise of the SLR as the 35mm choice for professional photojournalists and enthusiasts. While Zeiss had developed the first successful, fast 35mm-format long telephoto Olympia 180/2.8 Sonnar, back in 1935 (for the 1936 Berlin Olympics as the name implies), it was a very limited-production lens and it required a reflex adapter for practical use on the Contax rangefinder cameras then en vogue. SLRs basically incorporated that reflex box within themselves, making the use of focal lengths longer than 135mm (the upper limit of a rangefinder) a cinch. Nikon themselves had developed their own 18cm (180mm) f/2.5 lens for their S-mount (a few in M39 Leica Thread Mount also escaped into the wild :-)) rangefinders which was released in 1953. It weighed a staggering 1.7kg/60 oz. The 18/2.5 Nikkor-H could be adapted for use on F-mount SLRs, which added even more length and weight to more than a handful of lens ;-). With the proliferation of Japanese SLRs in the late-'50s and early-'60s, 200mm (and longer) lenses came right alongside. Nikon introduced their first F-mount 20cm (200mm) f/4 Nikkor-Q Auto in 1961 and some version would be sold for the next 35 years or so, even as they expanded into 180/2.8, 200/2, and 200/3.5 F-mount optics during that same period. The 200/4 would go from being a top-of-the-line offering...to budget option...to gone...within that timeframe. And it remains a largely-ignored focal length/aperture combination today. So what happened? And why might it be worth your time to give one a first or maybe a second look? The Rise of the 200mm Lens The development of 200mm SLR lenses progressed nicely through the 1960s, with f/3.5 being a "fast" aperture at the time, and f/2.8 confined to the drawing board :-). While many of their competitors offered two lenses in the 200mm category for part or most of the decade, Nikon split the difference by offering a single f/4 lens:

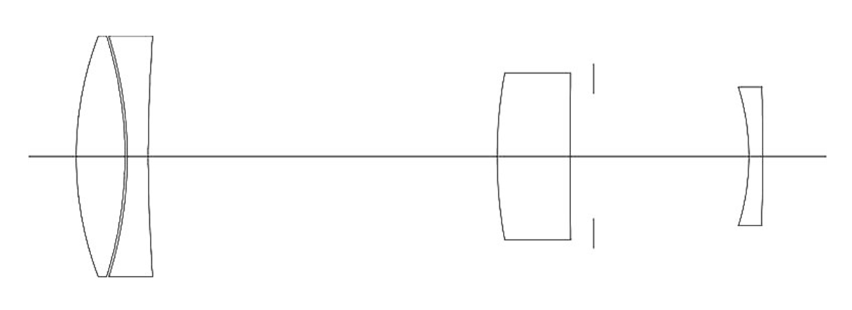

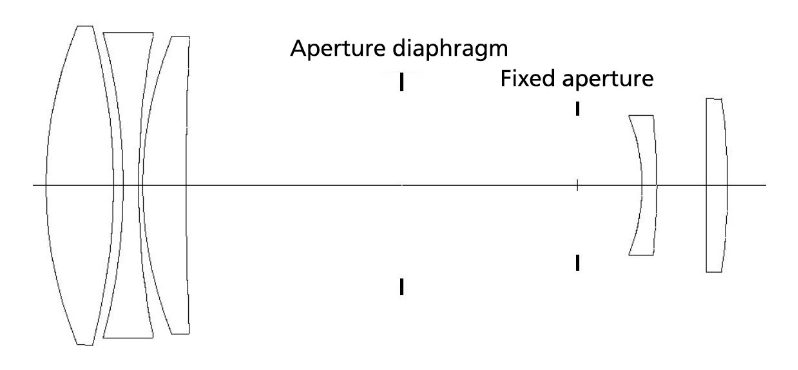

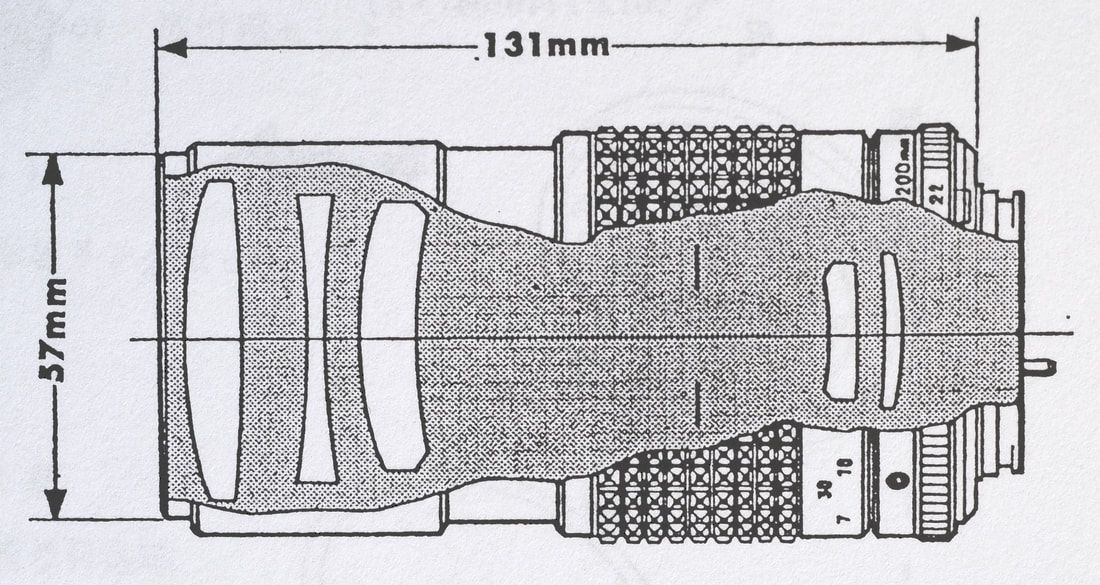

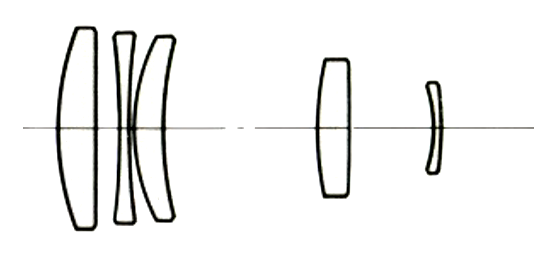

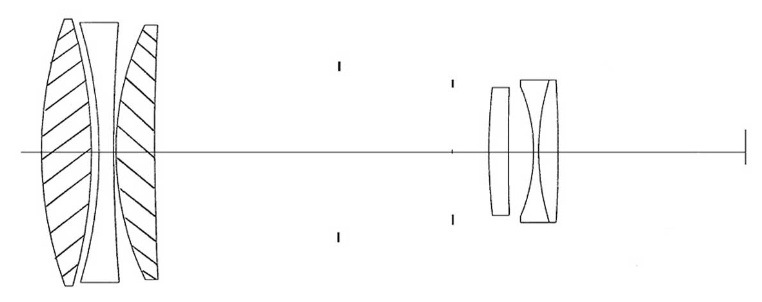

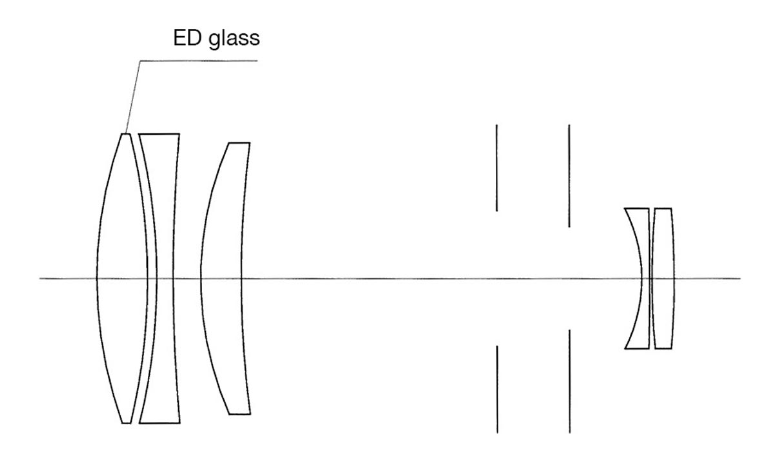

All lens manufacturers are faced with this dilemma of balancing performance, speed, physical size, and cost within the limits of their optical technology at any given time. With their original 200/4, Nikon opted for a moderate aperture together with a physically longer lens to accommodate the fact that they had no ED (Extra-low Dispersion) glass, no multicoatings, and no computer-aided lens design in 1959-61. By the early-1970s, major advancements had been made in all of those areas. Consequently, Nikon was able to introduce their first F-mount f/2.8 telephoto longer than 135mm: the 180/2.8 Nikkor-P Auto in 1970-71 (with a still-moderate telephoto ratio of 0.95x, by the way). What did that bode for our friendly 200/4? First, a bump down the Nikkor lineup ladder. The new 180/2.8 was double the price of the 200/4, pushing the latter out of its previous top-of-the-line role. Nikon also decided it was time for development of a full-scale redesign of the 200/4, whose basic formula was now a decade old, although it had been recently "remodeled" (in Nikon's own words) in 1969 for improved color balance (using newly-developed glass with a lower transmission of blue wavelengths) and resolution (achieved by improved correction of spherical aberration) which permitted a sizeable 1/3-reduction in minimum focus distance from 3m/10' to 2m/7'. Nikon also added another aperture blade (going from 6 to 7). Multicoatings would be added in 1973 (Serial # 570001 and up). Because of this relatively recent update to the 200/4 Nikkor-Q, Nikon could afford to take their time with its successor. And they did. Designer Teruyoshi Tsunashima would submit no fewer than four design proposals between March 1971 and February 1974 for what would become the New (aka "K") Nikkor 200/4 that was eventually released for sale a further two years later in February 1976. It would be the final 200/4 Nikkor optical design to date. The New 200/4 Nikkor With the arrival of the 180/2.8, the role of the 200/4 Nikkor was redefined, and this informed Nikon's decision-making when it came to the composition of the succeeding edition of the lens. Right from the first design proposal, Tsunashima-san knew that he would not be permitted to use the then-brand-new, extra-low dispersion (ED) glass that Nikon was implementing in its new 300/2.8 Nikkor-H super-telephoto then in final development. And this made practical sense: you do not put more expensive glass in a budget or standard lens than your premium offerings, and the 180/2.8 itself wouldn't get ED glass for another 10 years. In fact, in 1971, Nikon wasn't even yet able to produce its own ED glass; they had to purchase the FK52 (Fluour Krown) from Schott in Germany for the first production run of the 300/2.8 Nikkor-H to have the lens ready in time for the Sapporo Winter Olympics of 1972. The New 200/4 was not going to be a flagship lens, it was to be a workhorse and attainable for the average enthusiast photog. So what was Tsunashima left with? Maximize the performance of the lens with conventional glass types while reducing size and weight. Now it becomes apparent why it took him three years to come up with the final design. When you can't solve problems by just throwing money and premium materials at them, it pushes you harder and Tsunashima was up to the challenge, judging by the results. Granted, it's not like he had nothing to work with at all. During the decade-plus since the original 200/4 Nikkor-Q Auto was introduced, even conventional glass types had seen significant improvements and designers now had access to more sophisticated computer-aided design and calculation of optical formulas. But there was still plenty of trial-and-error involved as evinced by the multiple design proposals Tsunashima submitted. So what was he able to accomplish in the end? First, he was able to reduce the telephoto ratio of the lens to 0.8x, while still markedly improving optical correction and performance. That is noteworthy. Remember that increasing the magnification of the rear lens group to reduce the telephoto ratio leads to an increase in axial chromatic aberration (CA) by the square of the magnification increase. The 0.19x reduction in telephoto ratio produced a big jump in axial CA that would have to be rectified by the optics of the lens. The drop in telephoto ratio enabled a nearly-25% reduction in overall length of the lens, and Nikon was also able to trim the weight by almost 15% from the previous-generation 200/4 Nikkor Q-C. Something interesting about the New 200/4 was the inclusion of a decidedly non-budget 9-blade aperture, rather than the usual 7 blades for Nikon's standard lenses of the time. Perhaps Tsunashima-san was granted that small gift for having to sacrifice on the glass end and his three years of hard work. Or maybe it was simply a matter of beating Canon and their then-current, 8-bladed, 200/4 S.S.C. model ;-). Even the 180/2.8 Nikkor-P and AI models used "just" a 7-blade diaphragm (although it would also be upgraded to 9 blades when the ED AI-s version appeared in 1981). The general efficacy and acceptance of this basic 5-element formula for 200/4 lenses was borne out with its coincidental adoption by Nikon's competitor Minolta for their mid-'70s introduction of their own 200/4 optic (which replaced their previous f/3.5 & f/4.5 models in one shot). Minolta's MC-Rokkor(-X) was introduced just a couple of months prior to the New Nikkor in December 1975 and bears quite the internal resemblance: The Minolta lens could not quite match the New Nikkor's impressive telephoto ratio (0.85x vs. 0.80x) nor its 2m/6.5' minimum focus distance (2.5m/8.2'), and it only sported 6 aperture blades as was Minolta's standard at the time. It was 11% longer and weighed a touch less (520g/18.3oz vs. 540g/19 oz). Performance was nonetheless excellent and very similar to the Nikkor's. Not too shabby for a lens priced 40% lower. Filter size was 55mm. Note, too, the SMC Pentax 200/4 introduced in the Fall of 1975 that retained the basic 5e/5g layout of the 200/4 Super Takumar from 1965 but updated it with a closer focusing distance (2m vs. 2.5m) that matched the Nikkor's and improved SMC multicoatings over the first-generation S-M-C Takumar's. The SMC Pentax utilized 6 aperture blades like the Minolta and its telephoto ratio stretched even further to 0.89x. Overall length was 16% longer, but it undercut the New Nikkor by all of 5g/0.2 oz in weight. It was priced 45% below the Nikkor. Filter size was 58mm. All three optical designs are viewed as the highest performing 200/4 lenses each manufacturer ever produced. Both Minolta and Pentax would introduce newer, shorter (10% for the Minolta, and 20% for the Pentax), and considerably lighter (400-410g/14.3 oz) 200/4 lenses in the coming years, but both sacrificed some of their optical performance (shorter = lower telephoto ratio = more aberrations) as 200/4s faded in popularity and were pushed even further into the budget category. Nikon would knock a couple more millimeters off of the overall length of their final AI-s version and also trim the weight to 510g/18 oz, but made no optical compromises through the end of production. When compared to the Nikkor-Q, the new design offers noticeably better performance wide-open and is basically at peak capability from f5.6 to f/11. The older lens needs at least f/8 to reach its peak. The overall competence of the optical layout of the New 200/4 should not be surprising because of how closely it resembles the original 300/2.8 ED's (possibly a source of inspiration for Tsunashima) and it was further demonstrated when Nikon virtually reused it over five years later for the 180/2.8 ED AI-s with the substitution of ED glass for the front element. ED glass is harder to manufacture and work with than conventional glass, thus its higher cost. It is also more sensitive to temperature variations and is more delicate than standard glasses. Nikon did manage to improve the hardness and durability of their own ED glass over time but they still ended up having to add a built-in, protective front filter to the various newer 300 - 1200mm ED AI & AI-s lenses because of their exposed front ED elements, and it is a good idea to use a high-quality, multicoated 72mm UV or Skylight filter on the 180/2.8 ED AI-s, too. There is not much point in putting a cheap filter in front of good glass that can undo much of the performance built into the lens. No such worries with the lowly 200/4 :-). A further bonus is that any version of the New 200/4 can be had for the same or less money than the older Nikkor-Q(-C) versions, likely due to the predilection among vintage camera nerds for "all-metal" lens construction. For shame the New Nikkors would dare to use a rubber focus ring ;-). A Poor-Man's 180/2.8 ED AI-s? Obviously, the 200/4 cannot possibly match the overall imaging capability of its younger, faster, ED-equipped sibling. You can't beat physics :-). But, what the question really should be is this: "How much is that extra stop of aperture and bit of aberration correction worth to you, personally? Is it worth:

The 180/2.8 ED AI-s is rightly famed for its performance in astrophotography (one of those situations where determining infinity focus can be tricky, initially; stars are very hard to focus manually...after all it's dark out :-)), and was also a go-to for indoor sports and stage performances in its heyday. The bulk and weight are not a big deal for astro, since you would be mounting it on a tracking mount or tripod, anyways. But handholding it for the other activities could be a stretch for some. If you are more of a hiker/landscape shooter, the lighter weight and compactness of the 200/4 are major drawing cards. Now, you will always be able to find a hardcore 180/2.8 ED AI-s-wielding hiker somewhere, but we are talking in generalities here :-). The 200/4 will give you 90-95% of the performance of the 180/2.8 ED AI-s in almost any situation. If you happen to be shooting on any digital body made within the last 15 years, a simple ISO bump of one step is all you need in low light to keep up with the 180/2.8 ED AI-s, which also often needs a similar ISO bump just to keep the shutter speed high enough to prevent blurring with that extra weight swinging around when handheld ;-). If you can handle the 180/2.8 ED AI-s, you will not be disappointed. But the gains are incremental rather than monumental in most situations over the 200/4. Recommendations If you decide that a 200/4 Nikkor might meet your telephoto needs the best, what should you bear in mind? Seeing as the optics of the K, AI, and AI-s are identical, and weight only ranges between 30g/1 oz, there are only a few considerations when choosing one:

Wherefore Hast Thou Gone, O 200/4? The late-'70s were the last hurrah for the 200/4s of any brand. Nikon sold nearly 150,000 of the AI version over a four-year period from 1977-81. Compare that to just over 18,000 copies sold of the 180/2.8 AI (non-ED) for a ratio of 8 to 1 over the same period. The succeeding 200/4 AI-s version would accrue sales just above 80,000 over fifteen years as the Zoom and then AF Ages took hold. Third-party telephoto zooms (70-210ish mm focal lengths @ f/3.5-4.5 apertures) in particular became the undoing of the 200/4s. I can recall this from personal experience as a kid. Every person I knew with an SLR (including my Dad :-)) had a 50mm, a 28mm (usually aftermarket), and the aforementioned telephoto zoom (almost invariably aftermarket, usually a Vivitar or something similar, maybe a Series 1 if they were real extravagant; my Dad was not ;-)). And it isn't hard to see why, in retrospect, for the consumers that the manufacturers (Nikon included) were chasing at the expense of enthusiasts:

And that trend would only accelerate once the '80s came along. From 1977-85, Nikon sold over 502,000 manual focus telephoto zooms that reached 200-210mm at the long end. From 1977-96 (an extra 11 years) they sold just under 230,000 manual focus 200/4s (and nearly two-thirds of those were sold before 1982). Tellingly, no manufacturer has ever produced an autofocus 200/4 non-macro/micro lens. They simply let them die out. Zooms won. But did photographers? Well, there may have been more money left in their wallets and less overall weight in their camera bags, but there was no free lunch (funny how that keeps popping up ;-)). First, even the lightest, and arguably the strongest optically, zoom in our little informal comparison above is nearly 40% heavier in the hand than the 200/4 and that trend only increases with the shorter lenses it "replaces". It gets even uglier with the Vivitar duo: 67-75% heavier in the hand than the 200/4. And then there comes the optical performance. The highest compliment that could be paid to a zoom of the era was that it came close to an equivalent prime, optically. They simply had no hope of matching, let alone exceeding the latter, particularly at the long end of their focal range. The film SLR Zoom-era may well be called the "good-enough"-era. Performance was better than the plethora of AF lens shutter zoom point and shoots that came to dominate the sales charts for the next two decades, so that, taken with the convenience factor, was...good enough...for SLR consumers, and even many enthusiasts, as it turned out ;-). Wrap-Up Does everybody need a 200/4? Nope. Are there viable alternatives depending on your budget and weight restrictions? Absolutely. But I will posit that anyone would be up against it to come up with a better price-to-performance ratio optic in the telephoto range irrespective of the SLR system you have. They were made in sufficient quantities to avoid the age-old supply/demand dilemma; few of them were used extensively, so there is currently plenty of selection for copies in Excellent or better condition; and that moderate aperture also means less-expensive "standard" filter sizes (anywhere from 52-58mm, generally), of which there are boatloads of high-quality, used, multicoated copies to choose from. For half a century of "non-progress", I like mine just fine ;-). References: Roland's Nikon Pages @ http://www.photosynthesis.co.nz/nikon/lenses.html The Thousand and One Nights - No.10 @ https://imaging.nikon.com/imaging The Thousand and One Nights - No. 11 @ https://imaging.nikon.com/imaging The Thousand and One Nights - No. 48 @ https://imaging.nikon.com/imaging The Thousand and one Nights - No. 87 @ https://imaging.nikon.com/imaging SMC Pentax 200/4 Reviews @ https://www.pentaxforums.com/lensreviews Various Nikon Catalogs @ https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/rl/rlNikonNotebook Minolta SR Lens Index @ https://minolta.eazypix.de/lenses/index.html Minolta MC Rokkor(-X) Service Manual

10 Comments

Grant Goodes

2/12/2024 02:53:12 pm

Excellent (as usual) survey of the subject matter at hand. As a primarily wide-angle shooter (Nikkor 24mm/2), I must admit that my yearnings didn't go beyond 105mm for a long time, and then when I did decide to enter the telephoto fray, I was sucked in by all the professional-hype for the 180/2.8 ED, so bought a pretty beat up one rather than the minty 200/4 I could have got for half the money. In the end, although I loved the fantastic results of the 180ED, it was a royal butt-pain to carry and hand-hold, especially at the rock-concerts that I thought would be its forte. In the end I probably shot less than 1% of my shots on that lens, mostly because of the size&weight, as well as the difficulty of nailing focus at f/2.8.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

2/12/2024 04:00:49 pm

Nice to hear from you again, Grant. Especially regarding your literal "hands-on" experience with the 180/2.8 ED AI-s. On paper, the APO-Lanthar is very tough to beat: 485 grams, only 80mm long, 1:4 magnification. The only problem, as you said, is how much plastic it takes to procure one, nowadays ;-). With Poor condition copies sitting around $1000 USD and Excellent condition requiring 50% again as much, I can confidently say that it will be never be within my reach. Ah, the joys of limited production lenses ;-). Looks like I will have to be content with the Nikkors, too.

Reply

Michael Hagburg

2/25/2024 08:36:58 pm

Thank you for all the information on the 200/4. I shot many community newspaper sports photos with my AI-s in the mid 1980s. Finally got my hands on a 180/2.8 in 1992 but the fast AF zoom era was underway by then and MF was left behind.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

2/25/2024 10:00:16 pm

Hello Michael. Nice to hear from someone with hands-on experience with the 200/4 AI-s and glad to hear you enjoyed the article. Shooting sports successfully with manual focus is no small feat :-).

Reply

2/27/2024 06:35:04 am

Fantastic look at a great lens. I got one of these in 1979 when I traded a Vivitar Series 1 70-210mm for it! At the time, I had switched from Minolta to Olympus to Nikon in college (winter in Fairbanks was hard on gear) and had a 20mm, 35mm and 85mm. I bought the zoom used and just wasn't happy with it. When I went home to Ketchikan for the summer, I met a tourist with a 200mm AI who wasn't happy with that one, so we swapped. I had that lens until about 2009, when it finally was so darn worn that I sold it. But I immediately bought another one in new condition, and then an AI-S version in new condition. I still have both.

Reply

C.J. Odenbach

2/27/2024 02:49:37 pm

I can think of no better testimony to the effectiveness and sheer value of this lens than your experience, Gil. That is an amazing personal history with this lens, and thanks for taking the time to share it. And the fact that you were able to compare it back to back with the Series 1 70-210 is very telling about the level performance it offers. There is no substitute for boots on the ground experience when it comes to evaluating gear. Best regards.

Reply

I've had a yearning for this lens in my film collection. In the day (1989), I bought the new EDIF-AF 180 2.8. It was significantly lighter than the MF version and wow was it easier to focus than the MF beast. As for the mm preferences, I shot a 24, 105, 180 and 300. I never liked the 80-200. I did own a little Vivitar 70-150 f3.8. That was a particularly handy little gem. Compact and light.

Reply

Grant Goodes

4/12/2024 06:07:30 am

I assume since you bought the EDIF-AF 180 in 1989 that it was the so-called AF-n version, meaning crinkle-finish/metal exterior and wider focusing ring? I was immensely put off by the initial plastic-fantastic version from 1986, but the AF-n and AF-D versions corrected the horrible aesthetics, and I eventually picked up an AF-D when the advent of mirrorless killed the resale value of Nikkor-AF lenses. Agreed that the EDIF-AF is SO much lighter and easier to focus, to the point where I almost never bring out the MF lens anymore. Sure, the focus "feel" is gritty, not the silky smooth sensation of the MF lens, but my wrists and back appreciate the smaller lens.

Reply

The 180 EDIF -AF is one of Nikon's finest of that genre for certain. Much tougher than I thought it would be. Mine has a very smooth focus...maybe a touch too smooth...but i could move it with one finger. I bought the new version 300mm f4 EDIF-AF at the same time. Both were absolutely tack sharp. The f4 was smooth focuing and bright and the weight (and cost!) savings meant I could carry in my Domke and always have with me.

C.J. Odenbach

4/10/2024 10:23:57 pm

Nice to hear from you again, Matt. Coincidentally, I obtained my 200/4 AI-s from my friend Matt ;-). I can wholeheartedly recommend to give one a try. The size and weight are not far off from the Vivitar, although not quite as versatile in the focal length department :-). Thanks for taking the time to share your experiences.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed