|

Updated Mar. 8, 2024 Coming-of-age. If any term could be applied to Nikon's auto focus SLRs from 1986 to 1991, that one has to be at the top of the list. The transition to AF maturity coincided with Nikon's rise to second place in the overall SLR market to essentially form a duopoly with Canon as the other members of the then-Big 5 (Minolta, Olympus, and Pentax) slid further and further behind, and in Olympus' case, dropped AF SLRs completely. The irony in all of this was that Minolta had gotten the drop on everyone and dominated the first few years in AF SLR sales with their groundbreaking 7000 model. Canon brought out their T80 FD-mount SLR a couple of months after the 7000, and it wasn't even close to the Minolta. So much so, that Canon abandoned further FD-mount AF development and began a crash program to come up with a completely new mount and SLR system. It would be two years before they brought out the EOS 650. For Canon, that would turn out to be time well spent, as the EOS cameras rocketed them to AF SLR sales leadership in rather short order. Nikon got on the board in April of 1986 (over a year after the 7000 made its not-so-subtle entrance). While the F-501 did not surpass the 7000, it was the first true competitor to the Minolta and gave Nikon a toehold (and critically, a one-year head-start over Canon to get established in the market) until they could bring out their second generation enthusiast AF SLR in 1988. By the mid-'90s Nikon had clawed their way past Minolta and tried to maintain pace with Canon in market share (which didn't happen, but they did comfortably establish themselves in second place :-)). Let the retrospecting begin... A Brief History of Nikon AF Up to 1986 Nikon started dabbling with the idea of auto focus prior to 1971, when they introduced a prototype lens that used a built-in motor and sensor to achieve focus. Limitations in then-current technology prevented reducing the motor and power supply size to a reasonable level, among other things, so AF remained in the developmental stage for over a decade. By 1983, Nikon had managed to engineer two lenses with much smaller built-in motors (an 80mm f/2.8 and a 200mm f/3.5) that used a sensor and power supply located in the camera body. The Nikon F3 served as the platform, being fitted with a special finder (designated DX-1) that housed a twin SPD (silicon photo diode) phase-detect AF sensor and used two AAA batteries to power the lens motor. While only the two AF lenses were available, the F3AF's sensor could also be used as an electronic rangefinder with standard manual focus Nikkors. The F3AF did reach production, but was not viable as a practical AF camera. Nikon was anxious at the time to reduce costs when developing new cameras and lenses. The DX-1 module and and the two AF-Nikkor lenses were much more costly to produce than the standard F3 finders and manual focus (MF) Nikkor lenses, so there were two strikes already. More importantly, the AF performance was not nearly sufficient to offset these greater costs. Nikon's AF program was still in its infancy. And they were content to keep working away at it slowly and steadily until...February...1985.. ...and the Minolta 7000. This was an industry-changer on the level of the Canon AE-1 in 1976 and the Pentax Spotmatic in 1964. Every major Japanese manufacturer, whether they had already been working on AF or not, now felt the pressure to get in on this burgeoning AF SLR market. Nikon's reaction was particularly telling. They (like Canon) had heretofore been committed to the idea of putting the AF motor in the lens. But the smashing success of the AF-motor-in-body 7000, caused a major change in their thinking. By utilizing such a configuration, Minolta had been able to keep the size, complexity, and production costs of their new A-mount lenses very close to that of their MF lenses. This had tremendous appeal to Nikon, for a couple of reasons: 1) They were loath to increase production costs at a time when sales of manual focus SLRs and lenses were declining, and 2) adopting such a configuration would allow Nikon to utilize much of their existing lens technology (including the F-mount), cutting down on development time so that they could get a competitive model up and running against the Minolta. Nikon's motor-in-body screwdriver AF system would bear an eerie resemblance to Minolta's as a result ;-). That indicates the level of desperation they felt at the time. Canon, meanwhile, was unwilling to stray from its philosophy that AF-motor-in-lens was a superior concept, so they bit the bullet and took a longer development road to come up with more-compact lens motor designs that would enable them to compete on price and size with Minolta. Nikon introduced their first mass market AF SLR in April 1986, 14 months after the Minolta 7000 and 11 months before Canon would introduce their challenger (the EOS 650). The F-501 (N2020 AF in the USA) One glance at the F-501, and you can see "transitional" written all over it. It and its almost-identical, slightly older (Sept. 1985), manual focus sister, the F-301 (N2000), were positioned as replacements (and a bit more) for the mid-consumer-level FG (May 1982). While incorporating AF and automatic film winding (but not rewind) for the first time on a Nikon SLR, the F-501 still retained the traditional shutter speed dial and rewind knob that had graced most Nikon models since the original F. The new button and lever controls for the AF system made for a somewhat busier user interface than the FG's. The baseplate of the camera now housed four AAA batteries (you could also get the optional MB-3 battery holder that used 4 AAs for longer life). This had the side effect of forcing the tripod socket to be moved to to one side of the camera from the optimal centerline position. But the big question was...how good was the AF? Well...serious progress had been made from the time of the F3AF. The AF sensor was now made up of 96 charge-coupled-devices (CCDs) and could function with lenses having a maximum aperture of f/4.5 or larger. This improved on the F3AF's max. aperture limit of f/3.5. However, Nikon had not been able to better the F3AF's low-light sensitivity of EV 4 - 5 at best. This left the F-501 still trailing the Minolta 7000 by at least 2 EV. Overall performance in one word: Sllooowwww (from a modern perspective), but competitive with the 7000 in good light. The F-501 occupies an awkward place in Nikon AF history. It was a more than a consumer-level (but still not a full-on enthusiast) SLR that offered greater compatibility (full metering and electronic rangefinding with AI & AI-s lenses) with the MF Nikkor lens system than most of its successors would, yet its AF capability would soon be surpassed by even the lowest-specified second-generation Nikon AF models. Such was the price of being at the beginning of the AF development curve. One could say that "tweener" best sums it up. Typical of consumer Nikon SLRs, it lacked depth-of-field (DOF) preview, but atypically, it offered three user-interchangeable focusing screens (exclusive to the F-501; the F-301's screen was non-interchangeable), along with both single and continuous servo AF (which other consumer-, and even some enthusiast-level, AF SLRs lacked at that point in time). In a completely unrelated vein, it was also the final SLR introduced with the classic embossed Nikon script on its prism housing. All subsequent models would use the still-current, italicized Nikon logo. Lens Compatibility - Here comes the big bugaboo with Nikon's decision to retain the F-mount. This was done in the interests of backward-compatibility (newer bodies with older lenses), which the F-501 did very nicely with. However, forward-compatibility (surprise, surprise :-)), has become an ongoing and worsening issue as Nikon has introduced more modern technology to the F-mount. The following lens types are fully compatible with the F-501:

The following are not AF compatible, although they can be mounted, metered, and manually focused on the F-501 as long as they have an aperture ring:

The following are not compatible at all (no metering, aperture control, or AF, though they can be mounted on the F-501):

Verdict - The F-501 was Nikon's first mass-market AF SLR, and should be evaluated as such. Comparing it to a modern DSLR or even a second- or third-gen AF film body and expecting similar performance is stretching it just a touch ;-). Also, comparing it to enthusiast or professional AF SLRs of the period is likewise an exercise in futility. It was at least competitive with the Minolta 7000, and more so than any of the other Japanese manufacturers' first attempts at AF. So, is it worth it to get one? If you are looking at it from a performance perspective, then no. It's comparatively slow, noisy, and lousy in low light (after all, it was the '80s, baby). More modern film AF SLRs offer a lot more capability for a few (and I literally mean a few :-)) dollars more. But if you are drawn to the traditional control layout instead of LCD displays and push buttons and value excellent compatibility with MF Nikkors in a pretty reliable, compact, relatively light package, you just may want to check an F-501 out (or just get the F-301, if you want to skip AF completely; Nikon introduced their BriteView focusing screen technology with the F-301 & -501, and it makes a discernible difference in ease of manual focusing). If nothing else, you will be impressed with how far AF has come in 30+ years. The F-401, F-401s, & F-401x (N4004, N4004s, & N5005 AF in the USA) The F-401 was the first of the second-generation Nikon AF SLRs. It was produced, in three iterations, until 1994 (keeping the same chassis and control layout, but with AF improvements, and other tweaks that were introduced on the more advanced Nikons and then trickled down to the consumer-level). June 1987 brought the F-401 (it was priced about 20% below the F-501), and it was the first AF SLR to have a built-in through-the-lens (TTL) flash unit (according to Nikon, that is; Pentax also claimed to be first with their SF1/SFX which was introduced at the same time ;-)). The F-401 also featured a brand-new AF module with 200 CCDs (designated as the AM200, oh those zany Nikon engineers ;-)) and now with sensitivity down to 2 EV to match the Minolta 7000 (and the aforementioned Pentax). It was also able to AF with lenses having a maximum aperture of f/5.6 or larger, a gain of 2/3 of a stop over the F-501. A simplified 3-segment version of the AMP (Matrix) meter from the FA was adopted; however, if the user selected manual exposure or used the AE-lock, the camera automatically reverted to Nikon's traditional 60/40 centerweighted metering. The 3-segment meter was also used for flash metering, another first for Nikon. The adoption of a more prominent grip, and the vertical orientation of two of the four AA batteries in it, allowed for the tripod socket to be restored to its proper place. Obviously, given its lower price point, the F-401 was one of those cases where Nikon giveth and then taketh away. The deletions:

Due to its new AM200 module, the F-401's AF performance was upgraded to Slooowww. But its overall speed was hampered by very long shutter lag, even after AF was confirmed. It had a new twin-dial control system, but not as we think of in modern terms. The shutter speed dial was moved forward and now had an aperture control dial right behind it. The aperture ring on the lens was turned to its minimum setting and locked in place, ceding control to the dial. All four exposure modes (Program, Aperture-Priority, Shutter Priority, and Manual) were set between the two top dials. The F-401 was really intended to be used as a Program mode camera by Nikon, as there were no indications in the viewfinder of of the shutter speed and aperture settings and a rudimentary "+ o -" readout which the photographer could only be sure of to about 2/3 of a stop/step of exposure. The F-401s/N4004s (April 1989) brought the following improvements:

The F-401x/N5005 AF (September 1991) finished with a flourish:

Lens Compatibility - More Nikon giveth and taketh away. Here are the changes from the F-501:

Verdict - This one is easy. If you are interested at all by the control layout of these cameras or you have some screwdrive "G" Nikkors laying around, get thee to an F-401x/N5005 AF. It has all of the upgrades and deleted nothing from the earlier variants. Remember, though, that although the AF improved with every iteration (and was decent for the time), Nikon reserved the best AF performance for its higher-end models. You don't grab one of these for the AF primarily, it's all about the controls, (slight) weight-savings over higher-level designs, and ergonomics. Don't forget that these cameras do not meter with MF Nikkors (unless a CPU chip has been added to the lens). You'll need to step up to the mid- to high-level enthusiast Nikon AF bodies for that (again, usually for only a few dollars more in today's market). The F-401 was generally priced a bit higher than its main competitor, the Canon Rebel, but it offered a sturdier build (traditionally a Nikon strength, even with their consumer-level products), and had as good or better capabilities. Interestingly, the F-401x gave up nothing capability-wise to its successor the F50 (N50 in the US). Nikon went full-on push-button & LCD with the F50, with nary a dial to be found. The F-801 & F-801s (N8008 AF & N8008s AF in the USA) Remember at the outset, when it was mentioned that the longer road Canon took to develop the EOS was time well spent? Well, in the spring of 1987, this became apparent with the entrance of the EOS 650 and EOS 620 models. Although not quite as pivotal as the Minolta 7000, the long-term impact of these cameras is beyond question. Momentum began to shift back to Canon as it aimed to reclaim its leadership position in overall SLR sales. The EOS 650 & 620 borrowed much from the highly-advanced FD-mount T90, making them a formidable pair of challengers in the enthusiast-level market. Since the Nikkormat FT debuted in 1965, the enthusiast-level (or "prosumer") SLR had been the bread to the F-series butter in Nikon's lineup. Professional SLRs made Nikon's reputation, but they have sold more product to enthusiasts on the basis of demographics, if nothing else. So, when they were marking the jump to AF, Nikon had to come up with a winner in this market segment, especially in light of the success of the EOS duo. In June 1988, they did. Developed concurrently with the F4, which was released to market six months later, the F-801 rapidly became the backup (and sometimes primary) AF body of choice for pros, and amateurs also flocked to snap them up. And the F-801 maintained its popularity throughout its lifespan. Usually, when a model is going to be replaced, it takes a while to clear the vendors' inventory pipeline. Not so with the F-801. When the F-801s was about to be introduced in March 1991, the supply of older models had already dried up. The intrinsic strength of the F-801's design was also testified to by the fact that its successor, the F90, carried over much of its basic chassis and control layout. Innovations and features of the F-801 would also find their way into the lower-level Nikon SLRs as they strove to keep up in their ever-escalating battle with Canon. A few key features of the F-801:

But the the most pivotal feature was the control layout. Nikon had clung to traditional controls with the F-501, even as their competitors had jumped to exterior LCD displays and push buttons before that time. The introduction of the Canon T90 in 1986, with its combination of LCD and buttons + a multi-function dial, however, made a huge impression. The push-a-button + spin-the-dial configuration made for a simpler, more responsive control interface as more and more features were being stuffed into SLRs. With the F-801, Nikon decided to make its break with the past and embrace the present. With a right-side thumb-activated dial and a cluster of buttons on the left shoulder of the camera, where the rewind knob and ISO setting had resided on previous models, the basic control idea of hold-down-the-button and spin-the-dial used on Nikons to this day was established with the F-801. The viewfinder display LCD layout would also influence generations of Nikon SLRs to come. The F-801 was at the leading edge of Nikon AF technology when it was introduced. Nevertheless, that did not mean that it had every feature Nikon was capable of putting in an SLR. With the F4 coming hot on its heels, there had to be some means of elevating the professional model above the top amateur camera. And Nikon definitely had plenty of means:

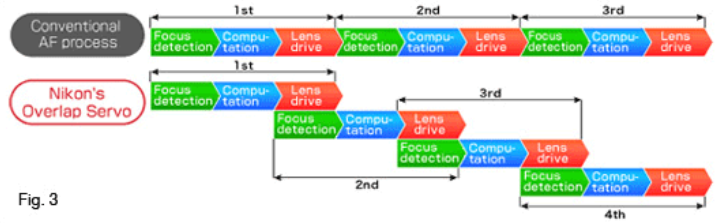

Nikon sensed a hole in their AF lineup between the F-401 and F-801. Hmmm, how to address that? With an F-601, of course :-). While we will take a closer look at the F-601 a bit later, its introduction had a direct impact on the F-801. When Nikon brought out the F-601 in September of 1990, the F-801 had been merrily going about its business for over two years. Two years was a long time for improvements to be made in the AF SLR wars of the time. So when the F-601 came out with a spot meter amid other improvements, the F-801 was due for an update to bolster its position as the top enthusiast Nikon. But there were not just internal forces at work here. By this time, Canon was pressing their advantage in overall AF speed (particularly with the EOS-1) and Nikon was struggling to keep up. And as reluctant as Nikon was to admit it, Canon was now setting the pace and it was Canon who kept Nikon's engineers awake at night. In Nikon's thinking, this was more a matter of perception in photographers' minds rather than outright performance. Nikon argued until they were blue in the face that motor-in-lens AF had no advantage over the motor-in-body configuration when it came to speed. Which was understandable, seeing as they had thrown their lot in with the motor-in-body brigade back in 1986. To backtrack now would mean a major loss of face. And when it came down to using standard focal length lenses (20 - 200mm), there was little or no difference. Magazine comparisons of the day found little to separate the two. But one problem with such tests was that they primarily used 50mm primes or standard zooms (35-70, or 28-70mm), which had small, light focusing groups. Where the Canons killed Nikon was with larger lenses and their heavier focusing groups (bigger pieces of glass are heavier :-)), such as the constant f/2.8 aperture zooms and 300 + mm large telephotos favored by sports and wildlife photographers. And Canon's powerful USM (Ultrasonic Motor) lenses were virtually silent to go with their speed advantage. Nobody could claim that for any Nikon body or lens of the time ;-). Now, at this point, the majority of Canon lenses were not USM models (only 9 out of 35 lenses introduced from 1987 to 1990 were USM, and only three of these cost less than $1,100 USD ($2,075 in 2017 USD)). But Canon wasn't going to let that stop them from promoting their advantages even though the average photographer would likely never get a whiff of them (by the mid-90s, USM motors were being incorporated into many of the consumer-level Canon lenses). Much as Nikon had done for decades, using the professional F-series' aura to rub off onto the lower-line models, Canon skillfully exploited the success of its high-end technology in the hands of pros to promote its consumer and enthusiast-level AF SLRs and lenses. The icing on the cake for Canon was that even its lowest-end body could utilize the full power of any Canon lens motor and was limited only by the capability of its AF sensor(s), whereas only the top Nikon bodies got the most powerful focusing motors. It was an uphill battle for Nikon all the way. The good thing for Nikonistas was that Canon's success forced Nikon to keep improving to try and keep up. So, an enhanced F-801 was inevitable. And in March 1991, the F-801s appeared with:

Lens Compatibility - As Nikon began to reduce backward-compatibility in the consumer-level bodies like F-401, it was left to the enthusiast level bodies to carry on the tradition. Here is the F-801's credit scroll:

Verdict - Why go for an F-801 when you can have an F-801s for the same price? I can't think of a reason, either :-). Today, for about a quarter of the cost of an F4, you can have a camera with 95% of its overall capability and 30% less weight. The F4 is the ultimate AF Nikon SLR for manual focus lenses, and if you prefer its traditional control layout and can live with the weight, by all means, go get one. The only other reason to not go with an F-801s is because you would be better served by its successor, the F90X. The F90X will get you the ultimate in Nikon single-sensor AF performance and the best forward compatibility with Nikon AF-S lenses in a very similar control layout to the F-801s with only 60 grams more weight (but with a considerable increase in bulk) for the same money. Within the single AF sensor Nikon family, the F-801s is the runner-up to the F90X as the preeminent choice for performance and value. The F90 will have its own article, as it was not merely an iteration of the F-801s, as its appearance might suggest, but it was really the first third-generation Nikon AF SLR. The F-601 (N6006 in the USA) The final second-gen Nikon AF SLR for your consideration is another "tweener". As noted above, Nikon sought to plug the considerable gap in price and capability between the F-401 and the F-801 with a model to match up more closely with Canon's EOS 10s (10 QD outside North America). Introduced in September 1990, the F-601 was the result. Deriving much of its control layout from the F-801, marrying this to the shutter (rated for 30,000 exposures vs. the usual 50,000 for the enthusiast-level Nikons) and built-in flash of the F-401s, and adding a spot meter and auto-bracketing to an amateur Nikon for the first time, the F-601 packed in a good amount of value. But here is the big bugaboo with this SLR: Nikon's move from AA-power to a DL223A (CR-P2) 6V lithium battery. On paper, this should have been no problem; lithiums are lighter, better in cold weather, and permit faster flash recycling, but many F-601 users (including Popular Photography in their Test Report of July 1991) complained of much shorter-than-expected battery life from the expensive (compared to AAs) little beasties, particularly when flash was used. As was noted earlier, the F-601 had a major effect on both the consumer and enthusiast lines. The F-801s and F-401x were direct beneficiaries of the development done on the F-601 as their feature sets were strengthened in the wake of Canon's continued onslaught. Lens Compatibility - The F-601 sported the AI coupler so using AI-modified, AI, & AI-s MF Nikkors was no problem (as long as you didn't mind having only A or M exposure modes and centerweighted or spot metering; CPU lenses were necessary for P & S modes and Matrix metering). There are a number of MF lenses that cannot be mounted on the F-601:

The following could be mounted but would give incorrect exposure:

As far as AF lenses go, F-601 compatibility is identical to that of the F-801. As a side note: there was also an F-601M (N6000), which was a non-AF version of the F-601). It sported Nikon's standard K2 manual focusing screen. This required the elimination of the spot meter due to interference from the central microprism/split-image rangefinder focusing aid. Exposure mode & metering compatibility were otherwise identical to the standard F-601 as far as MF Nikkors went. The built-in flash was also deleted, resulting in almost 100 grams lost from the F-601. With MF lenses it offered no technical advantage over the F-301/N2000 that it replaced, and with an interface that the few remaining MF holdouts found to their liking. Nikon sold maybe 70,000 of them. Verdict - Today, the F-601 suffers a bit from younger-brother-syndrome. Back in the day, its strong feature set made it a tempting choice for those who could not afford an F-801. It was the best bang for the buck as far as capability and features went. Now, with the values of this entire generation of Nikon AF SLRs having bottomed out to pretty much the same level, it's not so compelling. You get Many F-801 features, but with an F-401-level of durability. The battery situation doesn't help it at all, either. You can pop a set of 4 lithium AAs into an F-801(s) or F90(X) and have all of the benefits of lithiums for less than the cost of a single DL223A and waayyy longer battery life. The DL223A and other lithiums of its ilk were OK in small point & shoot cameras, but power-sucking SLRs were a whole 'nother ballgame. And the F-601 was even more egregious than its competitors... sucking way more juice for film rewind and flash operation than average. All in all, F-601s were decent cameras, they just have too much competition from their more-destitute big brothers, nowadays :-(. Conclusion So why even bother with Nikon's first- and second-generation AF SLRs? After all, they occupy that no-man's-land where AF performance wasn't awe-inspiring (especially compared to modern SLRs), they are relatively noisy, and they don't have nearly the same feel as the classic MF Nikon bodies? In two words: cheap thrills. If you are looking for the absolute cheapest way to get into a Nikon film body and cheap screwdriver AF lenses that feel cheap but are optically fine, you can't do better. We are talking 80 - 90% percent depreciation from their original prices. Most of the bodies use AA or AAA batteries (cheap). They are so cheap that you won't be afraid to take them places you might hesitate to take something more valuable, meaning more photo opportunities. And the AF is just fine for non-action situations if you want to use it. Yeah, they don't have the same feel as a classic MF body or lens, but the results on film are just as good and with flash are even better. The viewfinders are very good to excellent - no dark, cheesy pentamirrors here - you get real honest-to-goodness glass pentaprisms and BriteView screens that still work well for manual focusing. Try that with modern consumer (and a good many enthusiast-level) DSLRs :-). Recommendations - If your curiosity is getting the better of you or your wallet is thin, which of these relics should you choose? Let's work on the basis of IF & THEN. Now, the prices below are ones that I personally would not go above for copies that look to be good on the big auction site. You should be willing to pay more if purchasing copy that has been tested and confirmed to work from a reputable seller (who will also offer a bit of warranty to boot). I would also recommend trying to buy one with a lens (they are not uncommon) and that will maximize the value of the purchase. If the body turns out to be a dud, you will at least have a lens to show for it. IF:

IF:

IF:

Next time: The finest single-sensor Nikon AF body EVER. References: The New Nikon Compendium: Cameras, Lenses, & Accessories Since 1917 By Simon Stafford, Rudolf Hillebrand, Hans-Joachim Hauschild The Debut of the Nikon F3 @ http://imaging.nikon.com The Debut of the Nikon F4 @ http://imaging.nikon.com Camera Chronicle Part 15: Nikon F-501 and Nikon F-301 @ http://imaging.nikon.com Our Products History 1980s & 1990s @ http://imaging.nikon.com Popular Photography Magazine - SLR World column - June 1988 & May 1989; Autofocus Shootout - Dec. 1988; Nikon F4: Test Report - June 1989; Nikon N6006: Test Report - July 1991; SLR Notebook column - May 1991 & Dec. 1991 Nikon F4 & F-801s Brochures @ http://arcticwolfs.net/ Assorted Nikon Manuals @ http://www.butkus.org/chinon/nikon.htm Camera Hall EOS Film Cameras - Canon Camera Museum History Hall 1987-1991 - Canon Camera Museum

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed