|

Updated Mar. 16, 2021 The Pentax K1000. The Minolta X-700. The Nikon F3. When it comes to naming the Japanese 35mm SLRs that remained in production the longest, those three models are at the top of most lists with both the Pentax and Nikon breaking the two-decade barrier (21 years for the Pentax and over 20 years for the Nikon to be more exact), and the Minolta clocking out after 19 years. Unsurprisingly, all three of these models are very popular with film enthusiasts today, with the Pentax and Minolta routinely being recommended as "Best Beginner Film SLR" and the Nikon being lauded as an all-time classic and sometimes espoused as the "Best 35mm SLR of All Time". The objective of this article is not to wade into any fray over "the Best..." (seeing as what's best for me or you will not necessarily be the same in any case), but rather, to introduce you to another entrant in the longest-produced sweepstakes; one that receives far less notoriety, yet can prove to be an excellent choice as an introduction to film photography.

12 Comments

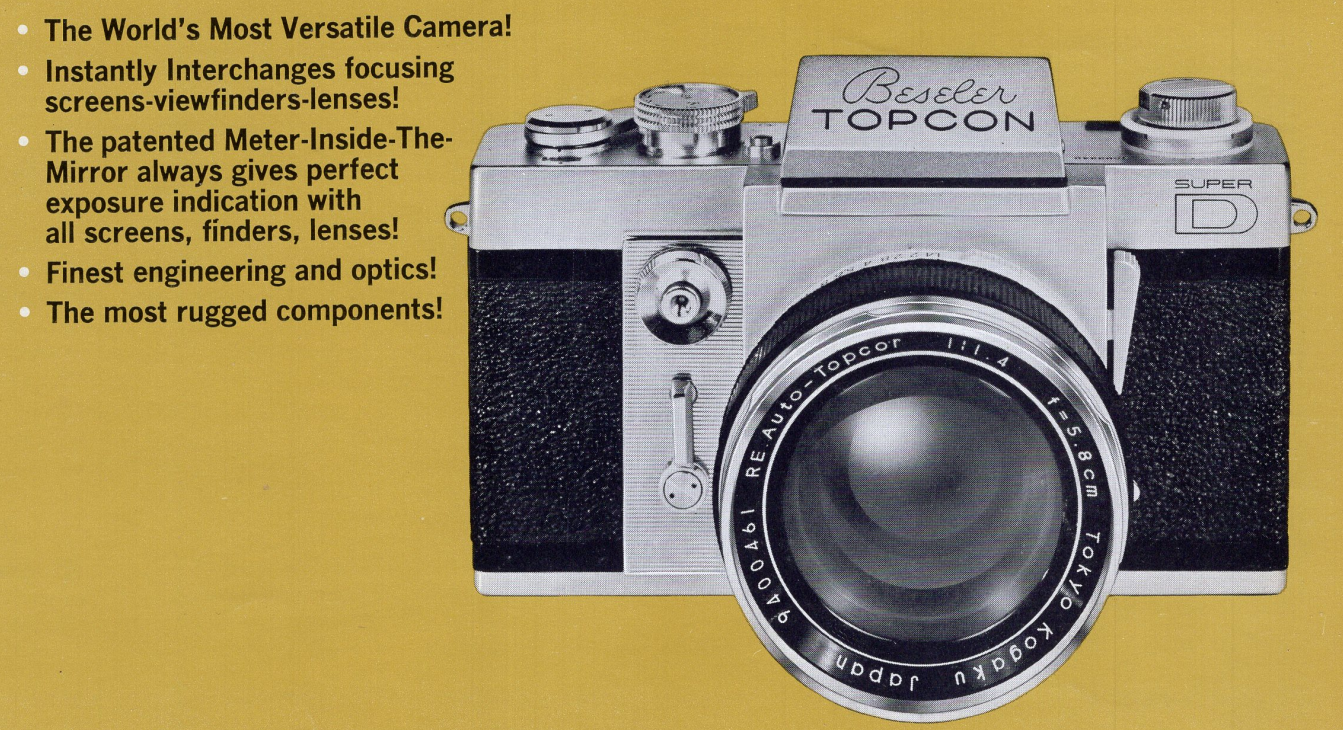

Updated May 2, 2023 Three decades...Six (and-a-half ;-)) models...ONE platform. Approximately 4.5 million bodies sold. That makes the compact enthusiast/semi-professional manual focus line of Nikon SLRs the longest-lived chassis in the history of the marque, and arguably, the most successful. Spurred on somewhat by the success of the Olympus OM bodies but mostly by the groundbreaking Canon AE-1, Nikon's foray into the world of compact SLRs first bore fruit in 1977 with the FM, and ended up with an "old vines" distillation of body and flavor with the FM3A in 2001. But there was a lot of ground covered between those bookends. So which one will be right for you? Let's dig in :-) Updated Mar. 9, 2024 With only a two-and-a-half-year market life (Spring 1983 - Winter 1985), it might seem that the Zoom-Nikkor 50-135/3.5 AI-s was a failure (just over 31,000 produced) for Nikon. Adding to this perception is the fact that it never made the transition to auto focus (AF), as did its pseudo-successor, the much longer-lived AI-s 35-135/3.5-4.5 (almost 92,000 produced from 1984 - 98 in MF and over 282,000 produced from 1986 - 98 in AF form). But when we dig a little deeper, a fascinating (for a lens geek, anyways ;-)) tale emerges. What were the real reasons for the 50-135's untimely demise? Here is the story of a sleeper Nikkor lens...one that still performs surprisingly well in the current digital age. Expectations. That is what it really comes down to. More than the optical performance, build quality, or outright cost (all of which can vary wildly) of any vintage aftermarket lens, it is your level of expectation that should determine whether you bother with them at all. If you are expecting OEM-grade (Original Equipment Manufacturer) performance and build quality out of something that was originally half-or-less of the cost, you are going to be disappointed. It is as simple as that. However, if you reasonably expect (oh come on, since when does that apply on the Interwebs ;-)) somewhat-lesser-but-still-capable performance from that $10 or $20 flea-market find, you may find yourself completely satisfied with a third-party alternative. Well now. That took care of that in short order. Cheerio... Okay...okay...okay. You know I can't leave well-enough alone. Read on if you feel the need for a long-winded, over-analyzed version of the above. Otherwise, just go out and keep snapping away with any cheap old light-sucker you find. After all, ignorance is bliss... ;-) Updated Jan. 20, 2023 1957. A year of events that would reverberate for years to come. Sputnik. The debut of cable TV in the USA. "I Love Lucy" ended production. The Cat in the Hat was published. And a musical duo that would be as influential as anyone on the next two decades' of popular music (the Beach Boys, Beatles, and Bee Gees were only a few among the many that would cite themselves as being significantly impacted by them) had their first #1 hit: 1957 would also see the introduction of the first 35mm SLR from a relatively small Japanese manufacturer that was to have an outsized influence on the industry that would continue for over thirty years. In that year, TOPCON (Tokyo Kogaku) would find themselves at the leading edge of 35mm SLR technology and they would remain there for the next decade. The 1960s would see them emerge as Nikon's (Nippon Kogaku) most serious competitor in the professional 35mm SLR market. By 1977, however, Topcon's photography division would be a shell of its former self, outsourcing its remaining SLR production and diving right to the bottom of the market. By 1981 (with Nikon owning over 75% of the pro market), Topcon was out of the 35mm business completely, even though they live on to this day in the industrial and medical optics arenas. So, what happened? How did Topcon go from industry leader to also-ran in the space of a generation? Updated Nov. 3, 2021 In an earlier article, we looked at the differences between the Nikon F3 & F4 and how they might affect your purchase and/or usage of either body. Not being able to leave well enough alone, I thought, "seeing as you can purchase an excellent F2 Photomic or Photomic A or a plain F3 for $250 - $300 USD, what if we tried the same sort of comparison between the F2 and F3?" I mean, what could possibly go wrong in attempting a dispassionate, objective analysis of two excellent SLRs made by Nikon? Oh...right...we are dealing with two groups of people: 1) those that believe that the SLR reached perfection in 1971 and everything since is an abomination against the laws of nature, aka "Knights of the Order of F2" (referred to henceforth as KOTOOF2), and 2) everyone else. ...waits 5 seconds... Okay...now that the pitchforks, torches, burning effigies, and other accoutrements to a rational discussion are at hand, let's wind the clock back to 1980 and the seismic shift that occurred in the Kingdom of F. Updated July 23, 2020 PROGRAM...the buzzword for SLRs in the early 1980's. Only with this technological breakthrough could photographers now surmount the barrier of having to think about camera settings and composition at the same time! Freedom from Aperture- or Shutter-priority or (heaven forbid you were still using) m...mm...mmm...Manual exposure beckoned. At last, focus (no pun intended) only on composition...unencumbered by such banalities...and our wunderkamera will do it all better than you ever could, anyways...(Okay, okay, that's enough...1980's marketing-speak now set to OFF). Riiight. Anyhoo, Program was going to be the next big thing to save the Japanese manufacturers from the the slippery slope of the latest SLR sales slide (Aside: it didn't ;-)). From the introduction of the Canon A-1 (1978), the first proper Program mode SLR (along with the three more familiar exposure modes mentioned above), to the 1985 introduction of the real "next big thing" (Auto Focus), the profligate proliferation of Program SLRs only accelerated. Followers included: Fujica's AX-5 (1979), Canon's AE-1 Program (1981) & T50 & T70 (1983 & '84), Minolta's X-700 (1981), Nikon's FG & FA (1982 & '83), Olympus' OM-2S & OM-PC/OM-40 (1984 & '85) , Ricoh's XR-P (1983), Yashica's FX-103 Program & the Contax 159MM (1985), and the two subjects of this article: the Pentax Super Program (1983) and Program Plus (1984). That's 16 models within seven years. So what set the Pentaxes apart from the rest of their competitors? Read on at your leisure ;-). In the first two parts (Part 1 & Part 2) of this series, a recurring cycle of market saturation and obsolescence as the drivers of the Japanese camera industry for the past five decades was clearly seen. The manufacturers relied upon a series of technological advances and clever marketing to combat these repetitive downturns. And as long as they remained the providers of such advances, their position as the standard-bearers of photographic capability remained secure. But in this 21st century, a major disruption has taken place, one that the Japanese camera companies collectively and individually failed to anticipate. Before we look at the magnitude of this disruption and its eventual outcome, let's briefly look at how things have gotten to this point. Updated June 18, 2022 In our previous article, we started searching for a possible precedent in the film SLR era for today's sea-change in the digital (and DSLR, in particular) age. Is Canon president Fujio Mitarai's forecast of a possible 50% reduction in digital camera sales within the next two years overly pessimistic? (UPDATE: As it turned out the decline from 2018 to 2020 came to 55%, so no it wasn't :-)) Sigma Corporation president Kazuto Yamaki's recent comparison of the current state of transition from DSLRs to Mirrorless ILCs (Interchangeable Lens Cameras) with the MF to AF SLR transition of the late-'80s begs further investigation. So, just how quickly did the transition from manual focus (MF) to auto focus (AF) SLRs as far as market dominance actually take in the late-1980's? Before we answer that, let's identify our Cast of Corresponding Characters. Updated June 18, 2022 "plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose" - Jean-Baptisite Alphonse Karr c. 1849 or as it is commonly rendered en Anglais: "the more things change, the more they stay the same" As of the spring of 2019, this maxim still rings true in the photographic equipment world (and the larger world in general :-)). ***FAIR WARNING*** - This series of articles contains numbers (please, no), history (bleccch!), and eventually, analysis (make it stop!). 678 Vintage Cameras cannot be held responsible for drowsiness, general lethargy or any other sleep-inducing effects should you choose to continue. Parallels are about to be drawn between the digital and film eras, which will be an immediate turnoff for adherents of the "either/or" crowd, and therefore an utter and complete waste of such a person's time. (As opposed to the standard waste of a person's time that this space traditionally occupies ;-)) Now that we've got that out of the way (is it too early in the spring for crickets to be out and about?), let's see how a 170-year-old saying relates to events in the camera industry today. In this first portion, we will look at the present state of affairs and some underlying factors, and Part 2 will deal with the breathtaking details of the Auto Focus revolution of the 1980s. (I swear I keep hearing crickets...) Today, weathersealing is taken for granted as a common, although not ubiquitous, feature in cameras. Over 30 years ago, however, it was rare in professional SLRs (the Pentax LX being the only model with what would now be considered to be even a modicum of such protection) and non-existent as far as any enthusiast or consumer-level 35mm model went. A plastic bag and some elastics were the standard means of improving the survivability of your rig in the rain or at the beach, with all of the compromises that implies. The time was ripe for innovation. And who better than Olympus to shake things up? In the manual focus (MF) era, the XD was arguably Minolta's biggest step forward technologically. It was the first 35mm SLR to feature both aperture- and shutter-priority auto exposure modes and all within the flanks of the first compact Minolta SLR body. The new form factor and added electronic sophistication necessitated the adoption of integrated circuits (ICs) by Minolta. The XD was thus far more complex electronically than its predecessor, the XE, which did have an electronically-controlled shutter and aperture-priority, but was still largely mechanical in its actual operation. The XD's basic electronic layout would prove to be the pattern for all subsequent manual focus Minoltas (including the XG and X-xxx series). And it was the XD that made capacitors front and central in the basic operation of the mirror and shutter assemblies of every succeeding Minolta MF SLR. Capacitor failures are few and far between with XDs and the majority of XGs, but became much more prevalent with the X-xxx series. My personal X-700 fell victim to "capacitor-itis" almost 20 years ago, but my XD 11 has never skipped a beat. That set me to wondering... Updated Sept. 13, 2021 Canon the innovator...Canon the boundary pusher...Canon the...wait just a minute! Are we talking about the same Canon that moves today at what appears to be a less-than-glacial pace? Nope, we are talking about the Canon of over three decades ago...the vintage Canon ;-). A Canon that, while still the market leader, was determined to meet a declining SLR market with more than retrenchment. From an all-time peak of nearly 7.7 million SLRs sold in 1981, by 1983 sales for all brands of SLRs had fallen by over 30%. Sound familiar DSLR users? Canon had wrung the last drops from their A-series of SLRs (1976-84), the most successful line of manual focus SLRs ever, and the catalyst to the SLR boom of 1976-81. The question now facing Canon (along with very other SLR maker) was: Where to go from here? Their first response would be the T-series of SLRs (1983-1990). So how did that work out for them? From a sales perspective, the T-series failed to accomplish Canon's goal of revitalizing the SLR market. Each model seemed bedeviled by at least one Achilles' heel. But one thing was for certain, the problems came down to execution and timing, not a lackadaisical attitude on Canon's part. And ironically, out of the (relative) failures of the T-series would come Canon's greatest period of success, the seeds of which were sown by the most tragic of the Ts...the T90. In automotive circles, the "sleeper" has a long and roguish history. Take a plain-Jane car and throw some serious performance bits under the hood and prey upon the unsuspecting (bwahahaha). A frumpy four-door with a quiet (at least at idle) exhaust makes it even tastier :-). When it comes to old SLRs, there is no such post-purchase hopping-up per se, but there were enough models that followed the spirit of the sleeper as far as looks and features went to make things interesting. The bonus today is that you can snag one of these soporific snappers for a fair bit less than their more-celebrated contemporaries, while giving up very little (if any) outright performance. Now, if I happen to leave out your favorite flies-under-the-radar film-burner, don't get uptight. Feel free to mention my misses in the comments, and who knows, maybe we will have to do a sequel. So...in no particular order... Just sit right back and you'll hear a tale, a tale of a fateful slip that happened to three companies who thought they were so hip... In Part 1, we focused on Pentax, Olympus, Nikon, and Minolta, respectively, as the first companies to introduce production auto focus (AF) 35mm SLRs in the early to mid-1980s. Although Pentax was the first-mover (1981), and Olympus & Nikon followed two years later, it was not until the introduction of the trendsetting Minolta 7000 in February 1985 that the AF SLR truly came of age. This was borne out by the other three manufacturers' abrupt decision to adopt Minolta's idea of AF motor-in-body (MIB) design, abandoning their previous allegiance to the motor-in-lens (MIL) philosophy. These companies' next AF SLRs bore an uncanny resemblance to the all-conquering 7000, at least in the lens mount area ;-). Minolta appeared poised to dominate SLR sales for the foreseeable future, yet within three years, they would be toppled from the peak and by the time the early-'90s rolled around, they would be back in their familiar third-place sales position that they had held from the early-'70s onward. So, even being the first successful AF SLR manufacturer was no guarantee of being the long-term winner. How could that happen? This time, we will take a closer look at the reaction to the AF revolution by the then-biggest fish in the SLR pond. Updated May 2, 2022 In the land of manual focus SLRs circa 1984, things were looking grim. That old implacable foe, "market saturation", had once again surfaced from the depths of the eastern Pacific to wreak havoc on the sales charts of the Japanese manufacturers. Over a decade had elapsed since its previous appearance in the early to mid-'70s. The proliferation of affordable autoexposure SLRs, from 1976 onwards, had not only blunted that attack, but had then led to the greatest sales extravaganza for 35mm SLRs, EVER. But now, the denizen of the deep was back with a vengeance and taking names. Internal motors for film advance, LCD displays, and angular '80s styling were doing nothing to stem the tide. Only another big-time innovation was going to give the SLR makers a chance. Their trump card? I don't know if Rodney Dangerfield was into photography, but if he was he must have used f/3.5 lenses, judging by the way he was always bugging his eyes out. Which would be understandable, because any half-baked photographer knows that f/3.5 is a raging vortex where photons go to die, leaving your eyes straining for the faintest trace of light. Not to mention the utter impossibility of achieving anything remotely resembling shallow depth of field (DOF) with such an infinitesimal iris. No proper lens jockey would be caught dead with such a miserable excuse for a photographic tool. So if you have any remaining shred of photographic self-respect, let me save you the trouble now of reading any further ;-). The 1980s were the heyday of the quality, yet relatively affordable, automatic auto focus (AF) 35mm camera. Competition was intense between manufacturers, and they were constantly trying to leapfrog one another in features and capability. Every year saw some kind of improvement until about 1988 or so, when the inevitable "race to the bottom" really started to heat up. Within this era, the years from 1983 to 1987 were arguably the high-water mark for quality and innovation, and some ingenious engineering. In this article, we are going to key in on a quirky category of cameras that served as a bridge between the original, fixed-focal-length AF point & shoots and the first P&S zooms: the temporary titans of P&S technology..the twin-lens (or bifocal) AFs. Updated Oct. 19, 2021 The mid-1960s were heady days in SLRland. From 1964-66 all of the Big 4 Japanese manufacturers brought out new top-of-the-line enthusiast models: the Pentax Spotmatic (1964); the Nikkormat FT (1965); Canon's Pellix (1965) and FTQL (1966); and the object of our attention in this article...Minolta's SRT (1966). The feature all of these cameras had in common was: built-in through-the-lens (TTL) metering. We take it for granted now, but five decades ago this was revolutionary. Of the five models, the Pentax and Canons used stop-down metering (meaning that the photographer had to manually close (stop-down) the aperture on the lens to get an accurate reading and then focus at maximum aperture). The Nikkormat offered full-aperture metering (the lens remained at maximum aperture for the brightest view and ease of focusing while the meter reading was taken), but required the user to manually index the aperture ring every time that they changed lenses. Then came the SRT-101. Full-aperture metering and the aperture automatically indexed whenever you mounted a lens. No muss, no fuss. And all it took was: Updated Oct. 19, 2022 At first glance, the FE (along with its slightly-older sister the FM) is as nondescript a Nikon as there ever was. Its specifications are nothing out of the ordinary for a late-'70s enthusiast SLR: 1/1000 sec. fastest shutter speed, Nikon's venerable 60/40 centerweighted metering, sub-600 gram weight, and a seeming dearth of innovation. Looks? Nothing to see here people...move along...move along. Flanking the classic Nikon logo on the pentaprism housing are two virgin swathes of metal betraying no clue as to the identity of this wallflower. Only once you go to bring the camera to your eye is there the possibility of positive identification, that is, if your right thumb isn't already covering the tiny "FE" that precedes the serial number on the rear of the top plate. But don't sleep on the FE, there is more here than meets the eye ;-). Canon got off to the slowest start of the original Big 4 Japanese camera makers (Minolta, Nikon, & Asahi Pentax were the others) when it came to SLR development and sales . This was partially due to their commitment to interchangeable lens rangefinders for longer than their competitors. By the mid-1960s, however, they had embarked on a slow but steady climb that would lead them to market dominance by the late-1970s. Their first truly competitive SLR was the FT of 1966, and it would spawn one of the finest series of mechanical-shuttered enthusiast SLRs of the age and Canon's most successful non-A-series manual focus model. The second- and third-iteration FTb & FTb-N would prove to be the backbone of Canon's amateur lineup in the first half of the '70s and sold extremely well while both Pentax and Minolta were facing declining sales of their excellent Spotmatic & SRT mechanical SLRs at that time. That alone makes it a pivotal model in Canon's history. But it is much more than a sales footnote, it was one of the best enthusiast-level SLRs of its day, and that makes it a great choice today for the film-SLR aficionado. You could call the FT the analog 5D of its era :-). Updated Aug. 11, 2023 1975 saw the introduction of the CONTAX RTS, the first camera since 1961 (when the Contax IIa/IIIa rangefinders were discontinued) to bear that moniker and which was the firstfruits of the technological alliance between Zeiss (owners of the Contax name) and Yashica, the Japanese camera maker (who did the actual manufacturing). The RTS (which stood for Real Time System, to emphasize the supposedly superior responsiveness of the body) was aimed at professionals and serious enthusiasts with pocketbooks sufficiently large to take on the task of mounting pricey Carl Zeiss glass in front of it. The RTS was a success, but as Nikon had found out two decades earlier with the F, having a single model camera lineup that aimed towards the high-end of the SLR market tended to limit opportunities for sales (less cameras sold = less lenses & accessories sold ;-)). So, four years later, in a move that mirrored Nikon's introduction of the enthusiast-oriented Nikkorex F in 1962 (followed by the more-successful Nikkormat of 1965), CONTAX/Yashica introduced their CONTAX-badged contender in the very-competitive amateur market. But what does this have to do with the Yashica FX-D? Let's find out :-). Updated Mar. 8, 2024 Maybe it has something to do with the application of the term "vintage" to items over 30 years old, but there is a dead space for most cameras (and many other manufactured goods) that are in the 15 - 25 year old range. Not elderly enough to evoke nostalgia, and far from the cutting edge of current technology, they languish in a veritable no-man's-land. The subject of this article, the F90(X), is in such a place today. If you are a 35mm bargain hunter, and are willing to look past its plebeian polycarbonate pelt...your ship may just have come in :-). Updated Mar. 8, 2024 Coming-of-age. If any term could be applied to Nikon's auto focus SLRs from 1986 to 1991, that one has to be at the top of the list. The transition to AF maturity coincided with Nikon's rise to second place in the overall SLR market to essentially form a duopoly with Canon as the other members of the then-Big 5 (Minolta, Olympus, and Pentax) slid further and further behind, and in Olympus' case, dropped AF SLRs completely. The irony in all of this was that Minolta had gotten the drop on everyone and dominated the first few years in AF SLR sales with their groundbreaking 7000 model. Canon brought out their T80 FD-mount SLR a couple of months after the 7000, and it wasn't even close to the Minolta. So much so, that Canon abandoned further FD-mount AF development and began a crash program to come up with a completely new mount and SLR system. It would be two years before they brought out the EOS 650. For Canon, that would turn out to be time well spent, as the EOS cameras rocketed them to AF SLR sales leadership in rather short order. Nikon got on the board in April of 1986 (over a year after the 7000 made its not-so-subtle entrance). While the F-501 did not surpass the 7000, it was the first true competitor to the Minolta and gave Nikon a toehold (and critically, a one-year head-start over Canon to get established in the market) until they could bring out their second generation enthusiast AF SLR in 1988. By the mid-'90s Nikon had clawed their way past Minolta and tried to maintain pace with Canon in market share (which didn't happen, but they did comfortably establish themselves in second place :-)). Let the retrospecting begin... Welcome to the final installment of our "Choosing Manual Focus Lenses" series. In this article, we will look at the larger picture of lens sets in general and also check out a few options for specialty optics, such as macros and shift lenses. |

C.J. OdenbachSuffers from a quarter-century and counting film and manual focus SLR addiction. Has recently expanded into 1980's AF point and shoots, and (gack!) '90s SLRs. He even mixes in some digital. Definitely a sick man. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed